A unique opportunity has arisen in the financial services world over the past decade or so: Investing in your beliefs. Now that isn’t to say donating to non-profits or your church, but the actual advent of investment products designed to allow you to invest in companies representing your beliefs or to avoid investing in those you don’t want to support. It’s not uncommon that someone will tell me they don’t want to invest in oil and gas or tobacco companies; after all, if you militantly avoid being a patron of these companies products, does it make sense to own the companies instead? Yet, investing in our beliefs often comes with complications, so let’s dig deeper.

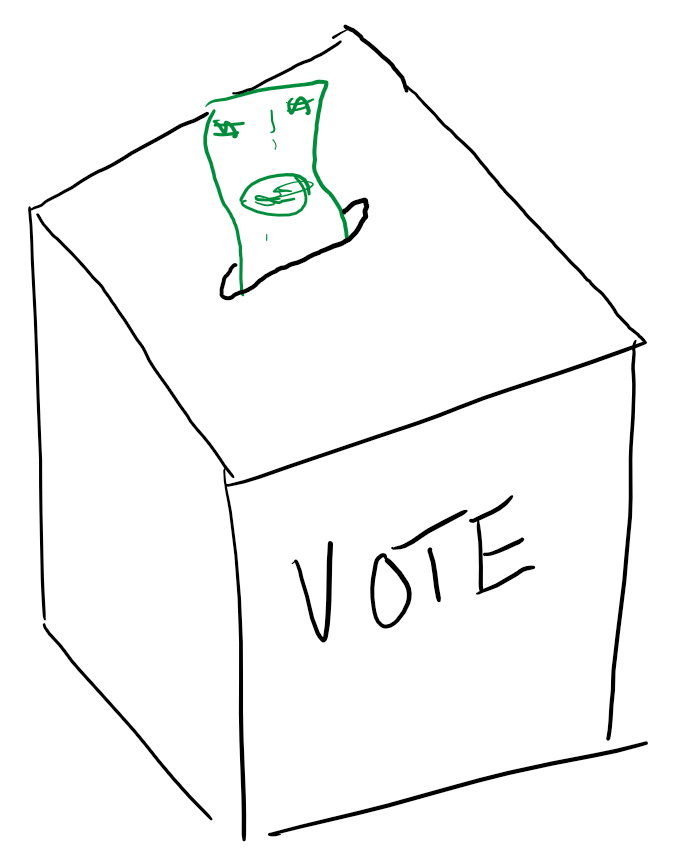

Voting With Your Dollar

There are three major categories of “belief-based funds”:

- Socially Responsible Investing (SRI), which focuses largely on investing in companies that have positive social impacts. It’s noteworthy that this is generally synonymous with progressive politics, and so it’s been heavily adopted in silicon valley and among the liberal affluent. The definition of “positive social impacts” can vary, but it largely focuses on companies that invest money in under served communities or advocate internally for the advancement of underrepresented demographics (minorities and women in leadership positions, anti-discrimination regarding sexual preference or gender identity).

- Environmental Social Governance (ESG), which is similar to SRI but has a broader mission of considering the “holistic impact” of companies operations. Does the company utilize green technology and reduce waste, does the company operate or provide products in a sustainable fashion or does it damage the environment in which it operates, does it advance the interests of underrepresented groups, does the leadership of the company have an equitable makeup and do they espouse community-positive beliefs?

- Moral Funds, which have no unifying acronym, but typically represent religious interests such as investing in companies that align with Catholic, Islamic, Jewish Orthodox, or other strict religious tenants. These are often viewed as oriented toward more conservative investors and are often at conflict with SRI or ESG funds, as religious tenants may orient a company to implement policies that conflict with the social or progressive mission of those funds.

The Cost of Beliefs

Notably, there is both a hard dollar and soft dollar cost to investing in belief-based funds. The argument is made by their proponents that funds that focus on social impact will likely result in greater long-term growth. “If this fund eschews an environmentally damaging company, it avoids the long-term risk that the company is regulated out of business. Or if the fund focuses on equitable and community-oriented leadership, the likelihood that a member of the C-Suite provokes a boycott by saying something outside the Overton Window is less likely.” These are all fair points and shouldn’t be ignored in the selection of investments. But with ultimatums come costs, both those of opportunity and explicit. Funds that actively exclude certain types of companies and industries run the risk of under performance in years that those particular organizations outperform the broader market. Further, belief-based funds can be expensive. While belief-based funds actually are lower in cost than the average actively managed fund, they are significantly more expensive than the average passive index fund (which naturally would encapsulate a large amount of companies), by a ratio of over 10 times the cost.

Voting with Other People’s Dollars

There is an additional risk that comes with belief-based funds, which is when other people’s money comes into the picture. While voting with your dollar is often applauded, business owners often start their companies with a mission in mind, particularly those in green endeavors or in non-profits that serve a social mission. When a business grows sufficiently, it will implement benefits such as a 401(k) plan to attract additional talent to the company. The risk arises when the plan sponsor (business owner) selects the investments for the participants or sets up the catalog of investments available for participants. Often business owners can see the retirement plan as an extension of the business itself, another opportunity to express the values and beliefs of the firm by aligning it’s investment options with the mission of the company. However, doing so co-opts the life savings of the employees into the political mission of the organization, and violates several federal laws regarding the sole purpose of a retirement plan (that the plan should exist solely for the benefit of the employees and their savings). Further, it’s actually a breach of the business owner’s fiduciary duty to the employees to place their politics ahead of more important factors such as cost, long term track record, and so on.

So why does it happen?

Simply put, we don’t know what we don’t know. For example, I know nothing about engineers, their professional ethics, code of conduct, or other professional requirements, let alone anything to do with the science of making and building stuff. Yet, business owners rely upon their support advisors to help them navigate complexities such as contracts and bookkeeping. Often the culprit lies in the over-simplification of the support. A business owner will ask their bookkeeper about a retirement plan, the bookkeeper will suggest a 401(k), and the business owner will set one up on their own or contact a vendor who provides the barebones infrastructure for the plan without any advice or guidance around the compliance of the plan. Yet any competent business attorney would have advised the owner against setting up the plan without the help of a plan administrator and investment fiduciaries to help; simply put, despite the best intentions of all parties, we simply don’t know what we don’t know, and that often can get us into trouble.