The United States has, by design, a politically polarized governmental system. While many other democracies practice with a parliamentary system, which utilizes proportional representation to allow for multiple small parties to build coalitions that result in majorities, the United States system favors deliberate disfunction. Concerned about tyrannies of the majority, the founders put in place a number of mechanisms to make it difficult for one political party to have total control at any given time, and this is rarely so distinct as our congressional system, which with a winner-take-all model results in a two-party system by necessity. As a result, many Americans consider themselves Democrats or Republicans, blue or red, liberal or conservative, and so on, which results in a certain amount of binary thinking. Today I’m not here to tell you which side is right about any particular issue, but to illustrate how regardless of your political preference, you are quite likely wrong about certain market and economic conditions due to your inherent bias.

Consumer Confidence

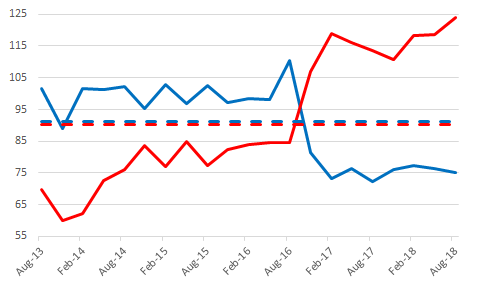

Consumer Confidence is measured by multiple organizations but is largely recognized to measure “how people feel” about the economy as a whole. When consumer confidence is high, we believe economic and market conditions are good (perceiving strong employment numbers, controlled inflation, a growing economy, and so on) while when confidence is low, we tend to think the worst of conditions. Despite the fact that the economy is objectively measurable by many very public and readily visible sources, our political affiliation heavily skews our perception of the economy. For example, prior to the election in 2016, Democrat voters were 41% more confident in the economy than after the election, while Republican confidence grew 37% within weeks of the election’s completion. While people might rationalize that their party having control of the executive branch is cause for confidence (and loss of control is cause for a loss of confidence), none of these belief systems sync with reality. The vast majority of the time, the economy is more or less indifferent to which party holds the executive office. Over the past twenty years, a realistic consumer would have felt confident up until 9/11, which would have shaken their confidence, then regained confidence shortly after until the great recession, then seen a protracted and growing confidence from 2008 until 2020 when we finally have had a significant GDP pullback as a result of COVID and our response to it. Yet, consumer confidence flips like a light-switch whenever their office gains or loses control of the executive branch, simply because of confidence in party control.

Source: Credit Institute for Policy and Opinion Research at Roanoke College

Foresight is Blind, Hindsight is 20/20

Without wanting to be too personal about this, you probably have no actual reason to believe what you believe about the future. This isn’t to say that you’re wrong or right about what will come to pass, but human beings are notoriously reliant on confirmation bias. Confirmation bias is best summed up as a desire to ignore or exclude information from our understanding of an issue if it doesn’t support our preconceived notions around the issue, while aggressively seeking or utilizing information that supports what we already believe. This mechanism is in place as a basic trick of neurobiology: It is easier for your brain to utilize pathways and structures already in place than to change how it works. Don’t believe me? Try writing with your off-hand and see how you feel about it. Your off-hand doesn’t lack any of the resources available to your dominant hand, only the habitual and ingrained structures of your brain to inform its movement. Getting back to how politics bias your beliefs, let me provide some anecdotal data: I keep notes of every client conversation that I have, both out of good practice and by regulatory necessary. When I read back through conversations, particularly looking at beliefs or concerns that clients have expressed at various times, they typically reflect a political bias towards an issue that didn’t come to pass. For example, in the three months leading up to the 2016 election, my conservative clients asked me about going to cash, investing in gold, or other “safe havens” in approximately 44% of our conversations. Post-election, those questions dropped to zero. At the same time, my democrat clients never raised any economic concerns until after the 2016 election, but I spent a large part of 2017 fielding serious concerns that the economy and market were going to tank under republican leadership. Often, as things come to pass, clients will remark to me that they “knew it was going to go that way”, but by reviewing notes of meetings prior to “the event”, there is no evidence or even contrarian evidence in place. Yet, both at the time and even with the power of hindsight, none of my clients could articulate tangible or specific reasons for their concerns. Ironically, now that the economy is facing significant headwinds in our response to COVID, it turns out the causality for a downturn in the economy has not been liberal or conservative policies, but a proverbial “act of god”.

Wealth vs. Income

This is less a political-ideological difference and more a basic thing to understand, but our political perspective warps our understanding. Wealth inequality is not income inequality, and inequality is not inequity. While higher-income affords you the opportunity to save more money, the majority of net worth growth is a product of saving over time and receiving compounding returns from that savings. Less than 3% of United States Millionaires inherited their wealth, and over 80% of the population will move between lower, middle, and upper class at some point or points in their lives (this can be up, down, or back and forth). Regardless, wealth inequality is regularly held up as evidence that wage growth has fallen behind, yet this is comparing apples to oranges. Wages in the United States have always largely followed inflation, and have otherwise only significantly adjusted with market demand for services increasing in new opportunities (software programming over the past few decades) or decreasing for aging industries (workers in factories and on farms). For example, while more and more people went to college and pursued four-year degrees, fewer people went to trade schools. As a result, the wages for electricians, plumbers, and mechanics have increased faster than inflation over the past few decades, while the wages of office workers, teachers, and entry-level administrators have slowed down to the level of inflation or even just shy thereof. Yet, another common misconception is that if people are all investing in the same things (index funds, amazon stock, etc.), then the net worth of the general public should be increasing just as quickly as it is for the wealthiest among us. But that was never going to be the case without significant outside intervention, due to the simple process of compounding math. When you get a 10% return on a $100 investment while a billionaire gets a 10% return on their $1,000,000 investment, you’ve both gotten the same return but that billionaire’s return was $100,000 while yours was just $10. Repeated over and over again, the wealth gap will continue to increase for the foreseeable future. The remedy to this on a personal level won’t be found in making “superior investments” or “betting big on a long shot”, but is more controlled and specific in pursuing education or qualifications for jobs that are in high demand fields such as technology. Otherwise, sans personal choices to make a change to income, advance in your career, or to take a risk and start a business (a major driver of wealth growth on the individual level), your wages are likely to grow more or less equivalent with inflation unless there is outside intervention. So where does politics come into this? Simply put: If you are liberal you are likely to see the inequality of income and wealth as inequity, but that’s not a fair comparison. If you are conservative, you are likely to consider income and wealth to be the products of hard work or lack thereof, but hard work is only a potential antidote to one of those problems and ignores the legacy of compounding factors in the other.

What does being aware of my bias do for me?

Well, simply put, it lets you make smarter decisions. You can’t eliminate your bias, but by being aware of your natural inclination toward one belief or another, you can carefully approach market and economy issues with the understanding that you might be prone to one outcome over the other. If you are conservative and you see a social program being touted, don’t simply assume it’s a redistribution of wealth that’s going to take money out of your pocket and put it elsewhere. The results of that social program might just produce enough social good that it does genuinely raise all ships. If you are liberal, don’t assume that because something was put forth by the current administration, that means that it must inherently be bad. When you read statistics or arguments over politics, be very clear about what the data actually says and not how the author is summarizing it for you. If you approach contentious issues that you feel strongly about with a layer of skepticism toward your own opinion, you might just catch yourself before you make a mistake.

Comments 2

Wise words. Thanks

I appreciate your clarity that comes through in your presentation. Calm explanation is very important. And I hope you will write fiction one day.