The United States has, for many decades now, emphasized above many options “the value of an education.” A significant portion of state and federal tax dollars is spent on K-12 education, with some states going further and providing additional funding at the undergraduate collegiate level and beyond. This cultural trend was magnified at the end of World War Two, when 16 million Americans completed their tours of duty, many of whom then qualified for the newly minted “Montgomery GI Bill” which at the time could pay for tuition at a level that could even cover attendance at Harvard. Thus began a long sequence of generations that would see college attendance by most American young adults on a going-forward basis. However, as time has gone on, and the cost of education has risen, the cultural trend of “must attend college” has steadily turned sour. Student loan debt has ballooned to 1.59 trillion dollars, one in four college attendees is in default on their student loan debt. While the quality of life has grown steadily as a national average, wages have stagnated in most fields. This week, we’re diving into the mechanisms behind whether education is a worthy pursuit, and what those out of school can do to help those facing the choice.

The Politics of Learning

While few people would argue that knowledge for knowledge’s sake is bad, the conversation turns a different direction when it comes to the outcome of an expensive multi-year pursuit. While students may enjoy debating ethics with their professors, disagreeing in political science theory classes, and reframing their understanding of common issues, there is often very little tangible reward for doing so. In fact, the “skills” developed in a well-rounded education are so poorly matched for the workplace that employers regularly complain that new graduates struggle to communicate professionally, lack the foundational skills needed for the job they’ve been hired to do, and have not adequately developed the “resilience” required of mature adulthood and the responsibilities of work. This isn’t merely an “ok boomer” backlash; these are the results of survey after survey for years that have shown an ever-widening gap between what students are learning in school and what they need to know to perform work. In fields such as personal finance, it is perpetually bemoaned that students will be required to take a minimum of three mathematics classes in high school but never take an introductory personal finance course at any point. Meanwhile, medical schools are seeing an increase in applicants and a decrease in the average quality of their MCAT scores and GPAs. Succinctly, despite a four-year pre-med education, students are learning to deploy what they’ve supposedly learned less effectively. However, much of this stems from the “politics” of learning, in which the many domains of learning emphatically argue that students will be set up for catastrophic failure if they don’t at the very least take this handful of 3-5 absolutely essential classes. After all, society itself would collapse if we hadn’t taken at least nine credit hours in the history of art theory, right?

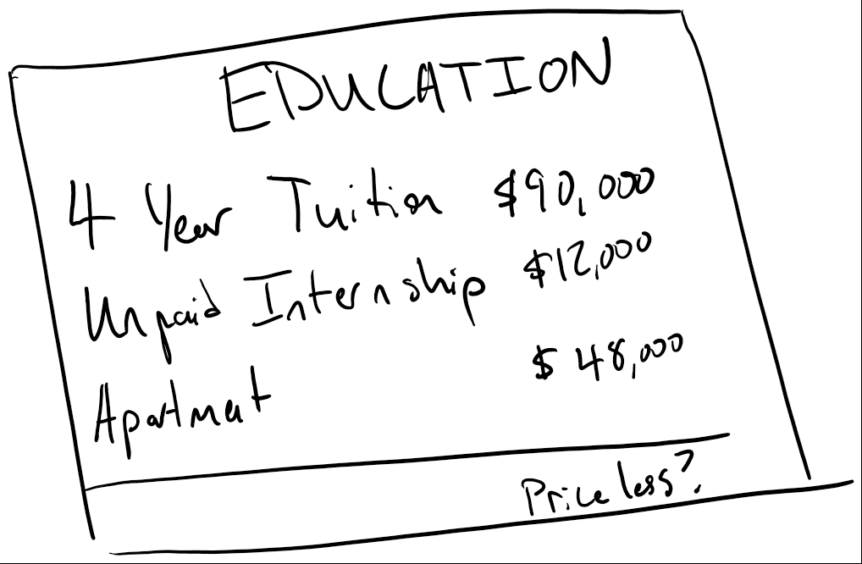

The Cost of Learning

As with the expansion of “necessary” education, so too has the cost of education. While inflation has bounced wildly since the initial growth of formal education, educational inflation has been a bit more constant. While it has risen to the high watermark of inflation in years where inflation has been high, it has failed to decline consummately; thus, while in periods such as the 1980s where inflation sat in the high teens, inflation followed, but in the past two decades where inflation has struggled to rise any higher than three percent, educational inflation has never dipped below six percent. As a result, just over the past twenty years, the gap between an inflation-adjusted dollar and an education adjusted dollar has been 196%; or rather, an educational dollar buys less than half what it used to twenty years ago. So what has driven this particular spree? Simply put: a blank check. What any business can charge is primarily derived from what price the market will bear. In fields such as medicine, where there is significantly less supply of medical professionals than the demand for medical care, this results in high prices. Among products such as video games, the market for products is mostly homogenous and ultra-competitive, which has seen the price of a new video game remain at a level of $59.99 over the past 16 years! However, because most educational spending by the public is financed by federally backed student loans, there is little to no behavioral financial constraint. Faced with taking on a loan that has little correlation to the product received (quality of education varies wildly, but students mostly can’t tell the difference), students sign away their future income in the form of debt payments, mostly without taking time to truly understand the future costs they’re assuming on their own behalf. Thus, faced with an unconstrained “blank check,” Universities have taken free license to bake every imaginable cost into their tuition.

The Value of Learning

However, all this naysaying doesn’t come without a silver lining: There is an intrinsic value to education. Very few majors produce qualifications for jobs that result in lower than high school graduate average wages. Even those bereft philosophy of dance majors can find something paying at least a penny more than minimum wage! However, the challenge then comes from the low ceiling of wages. For example, becoming a teacher in the state of Colorado requires a Bachelors degree, a teaching certificate, and hundreds of hours of unpaid externship hours before ultimately going into a field that demands well over forty hours a week of work, not including various club sponsorships, continuing education, and meetings that will stack on top of their weekly responsibilities, ultimately amounting to annual incomes that when divided by hours worked amounts to barely over minimum wage. This is then further compounded as newly minted professionals begin to pay out 10%-20% of their gross wages to pay for their student loan debt, which can effectively drop their net income below minimum wage, though it likely will come with better benefits than the average high school entry-level position.

How do you help?

Well, first of all, stop using a college education as a metric for capability! While specific fields and professions demand a formal education (law, engineering, medicine), many fields use Associates or Bachelors degrees as screening for candidates, despite the roles often being filled being little more than call centers, reception, or paperwork management work. Education is a valuable tool in anyone’s belt, but you should evaluate the education’s actual necessity for the role being offered. Similarly, help the young people in your life make smarter choices around where they are going out of high school. Suppose a student is unclear about what they want to study in college. In that case, you should direct them to a community college and some lowest-cost general education options to get their feet wet and pique their interest in an assortment of topics. There is no reason to pay easily three-to-ten times the cost to send them to a formal four-year institution just to decide they don’t know what they want to do. Alternatively, for those who know they don’t want to pursue a formal education, direct them to apprenticeships, trades courses, or low-cost self-study certification programs that can qualify them to move closer to something they’d like to do long term. The only option that should be avoided at all costs is “I’m just going to work and save before I go to school”. At the same time, there is nothing wrong with working between educational experiences or working while in school. The cost of education is still inflating faster than anything else! As a result, it is critical that once a student has an educational goal set, that they pursue it as soon as possible.