In 2020 stock buybacks came under attack, and it was no surprise. The public was outraged to learn that airlines had collectively engaged in over $25 billion dollars in stock buybacks over the past decade. “How can companies making that much money suddenly not have the cash to operate?!” Was the question of the day, and a fair one at that. Well, I’m here to disappointingly tell you that it was the job of the CEOs and board of the companies to engage in those stock buybacks to fulfill their fiduciary duty. I write about fiduciary duty as a financial planner here quite frequently, but today I’ll be explaining why those stock buybacks likely benefitted you over the past decade and how they continue to do so.

The Fiduciary Duty

Public companies are owned by thousands if not millions of people. Corporations such as Apple, Johnson & Johnson, and the like, are majority owned by public pensions, mutual funds, and other investment vehicles that you likely use as part of your retirement portfolio or investments. The leadership of these corporations answer to their boards, and in turn those boards are elected by the shareholders of the company (albeit, you probably haven’t personally voted, but your mutual fund managers certainly have). The management of these companies have a fiduciary duty to shareholders to fulfill the legal definition of a business’ purpose: to make a profit for the owners. This driving intent occasionally manifests in interesting ways, such as companies donating a percentage of profits to charity, or making stated ecological missions part of their company mission. Ultimately these “not-for-profit” activities, too, are intended to drive the longer term health of the company, and as a result, to produce greater value for the shareholders over time.

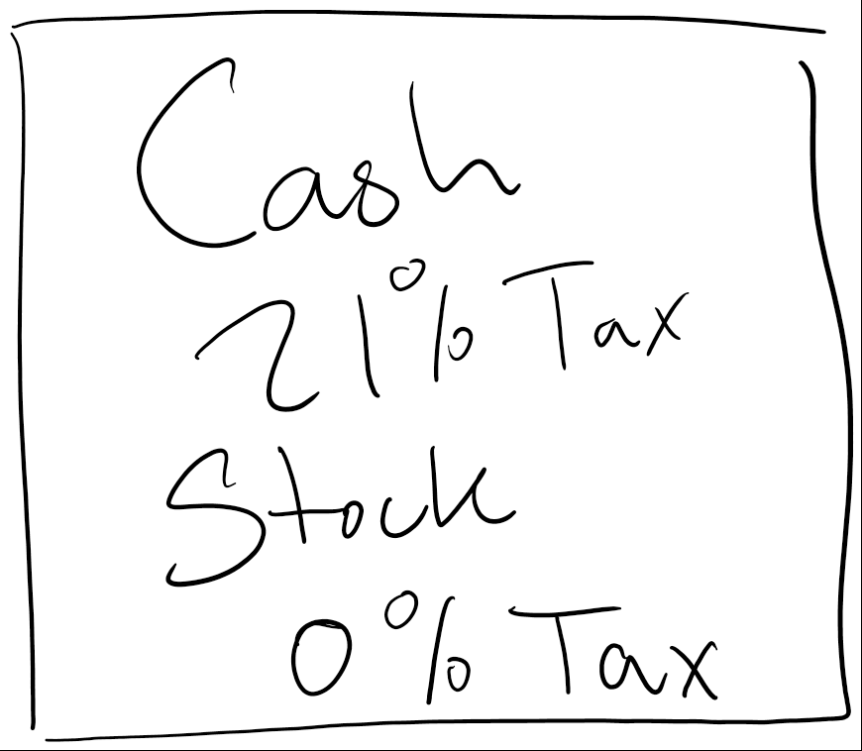

The Taxation of Profit

Every publicly traded company in the United States is classified as a “C Corporation”. As a C Corp, the company pays for operating expenses and activities out of revenue, and at the end of the day, any remaining cash and profits are taxed at the corporate tax rate of 21%. Once that taxation has occurred, any remaining cash can either be retained for operations in the company or paid out to shareholders as a dividend. If a dividend is issued, then it is taxed again on the returns of the individual stockholders who receive the dividend. The taxation of this event is very important, as it drives much of the decision to engage in buybacks. You see, the choice of the company management to pay a dividend is complicated by how a dividend is issued. Let’s say you own a share of stock worth $100. If the management of the company decides to pay a $10 dividend, the moment that dividend is issued, the price of the stock will drop a consummate amount, in this case, to $90. Thus, your $100 share of stock is now a $90 share of stock and you have $10 in your account. However, if that account is a brokerage account rather than a retirement account such as an IRA or 401(k), that $10 will be subject to taxation, and depending on the nature of your tax situation, you could end up with as little as $5 of the $10 dividend. Thus, the profitability of the company actually robbed you of wealth due to the taxes. Before the dividend you had $100, now you might only have $95.

How are Stock Buybacks Different?

A stock buyback is a pre-profit business activity. Like any other business expense, when the corporation decides to spend cash on something (a new building, new software, computers, etc.) that money ceases to be profitable and has the potential to be reported as a business expense, which means it won’t be subject to the same taxation as profits. The same occurs when the company decides to purchase shares of itself. By doing so, the company is converting taxable cash profits into a potential expense (which we’ll cover in the next section). Thus, by doing so, it avoids taxation on the purchase of the stock (if deployed correctly), but at the same time, has likely converted the value of what would have been a taxable dividend into a demand for the stock. By increasing demand, the price of the stock shares is driven up, thus, the company not only now has more assets on its books (the company stock), but the value of its shareholder’s stock has been directly increased without causing a taxable event. Notably, there is some risk in this strategy, as demand could still shrink in the future and the value that might have been locked in as cash could now be lost to market volatility.

Editorial Note: CPA friends of the author have noted that this is a gross oversimplification of the financing, deduction, and taxability of stock buybacks, and the author. You should be aware that the process for financing, writing off the interest expenses, and so on of a stock buyback are much more complicated than this, but in writing for a lay audience we find it beneficial to keep things simple, if potentially lacking in nuance.

What is a company going to do with all that stock?

The stock will generally be deployed in one of three ways. First, the company will likely use stock as a major part of its C-suite’s compensation packages. By paying a CEO in stock rather than in cash, this incentivizes the CEO to perform activities in alignment with the shareholder’s mandate: to make the company more valuable by increasing the value of its stock. Second, the company can later sell the stock to raise cash for specific projects, but in controlled lots (i.e. selling 1/10th the amount of stock they bought), and then by spending the cash on those projects, continue to avoid cash profits which avoids potential taxation. Finally, many companies utilize “restricted stock unit” bonus programs for their employees. In this type of compensation, an employee is granted a vesting block of stock, say 400 shares, which will vest every six months in the amount of 50 shares. By doing so, the employee is incentivized to stay with the company for the next four years to receive their vested shares, and the employee is incentivized to create value for the company to increase the value of their stock compensation.

How is any of this legal?

Well, herein is the tough truth about our tax system: It is a complicated set of rules, and corporations have significant teams of lawyers and accountants whose job is to reduce the tax obligations of the corporation through this sort of activity. While we might decry the fact that Amazon has effectively never shown a profit and therefore never pays corporate income tax (or very little), we should not forget that Amazon pays over 575,000 people every month for their work, along with paying into social security taxes and medicare taxes as part of the payroll tax. While we might get angry that billionaire’s wealth has increased by a collective trillion dollars throughout a pandemic, that’s simply a symptom of the value of their company increasing, not their company paying them enormous billion dollar cash dividends. And ultimately, while the drive to perform stock buybacks reduces cash on hand and creates an environment where companies like the airlines needed a bailout in 2020, we are generally the beneficiaries of all of this tax avoidance. In our 401(k)s, PERA pensions, and other vehicles, we (the general public) are still the majority shareholders of these companies and ultimately the mandate to increase value while avoiding taxation does benefit us.

So are stock buybacks moral?

Well, as a simple resident of Longmont, CO, and as a financial planner, I leave that for you to decide for yourself.

Comments 2

Marvelous read! It’s so funny because I was actually explaining this to someone the other day. The goal of which to incentivize productivity.

Simplified it may be, but still a stretch for this brain to comprehend. I do get the bottom line, convoluted as it is, that we do benefit from the big company bailouts.

But, what about those fabulous vacations provided for the managers and CEO’s soon after the bailout money was received? Is there some intricate books juggling that makes that into a benefit for the rest of us tax payers?