In the United States, we have a national pension and disability insurance system called Social Security; you may have heard of it. Originally established in 1935, social security started as a safety net to provide the elderly, widows, and orphans with some form of supplemental income. At the time and since that time as the program has developed, the concern was that the most vulnerable populations in the country would be left without means in the event of financial loss or family tragedy, and it has been decided over the years that social security would extend to many other issues such as support for children with disabilities, incapacitated adults, and others. Much of these benefits is administered at the state level, and I think we can all agree that the needy and helpless in our society should be supported by those who can. However, today I want to talk about the issues with the incumbent pension system for the United States, and my belief that it is a major contributor to wealth inequities in the country suffered by different groups.

Let’s Talk Benefits

Without turning this piece into an education spot on how you accrue benefits under social security, here’s the baseline: If you earn at least $1,470 in any given quarter of a year, you receive a credit. You must receive 40 total credits to qualify for social security. Your benefits for social security are then based on a calculation of your best 35 working years (or less if you didn’t work for a while) and at the ripe old age of 67 (a few months younger for those born in the mid 20th century or up to a few years later if you delay) you will receive a monthly benefit until you die, and your spouse also may receive some benefits. Social Security is able to provide each senior citizen a cash benefit that is supposed to be greater than what a portfolio could afford because of a concept called “mortality credits”, in which the natural life expectancy of some adults doesn’t hold true, whether that means they live longer or die younger. As a result, those who live longer and receive more benefits are subsidized by those who don’t make it to retirement or die earlier in retirement. Bear in mind, the program is also the source of funding for disability benefits for some 10.1 million adults in the United States (as of 2016), so there is also money leaving the program much earlier in some people’s lives for the benefit of the disabled, who may receive substantial support over their lifetimes.

The Funding Problem

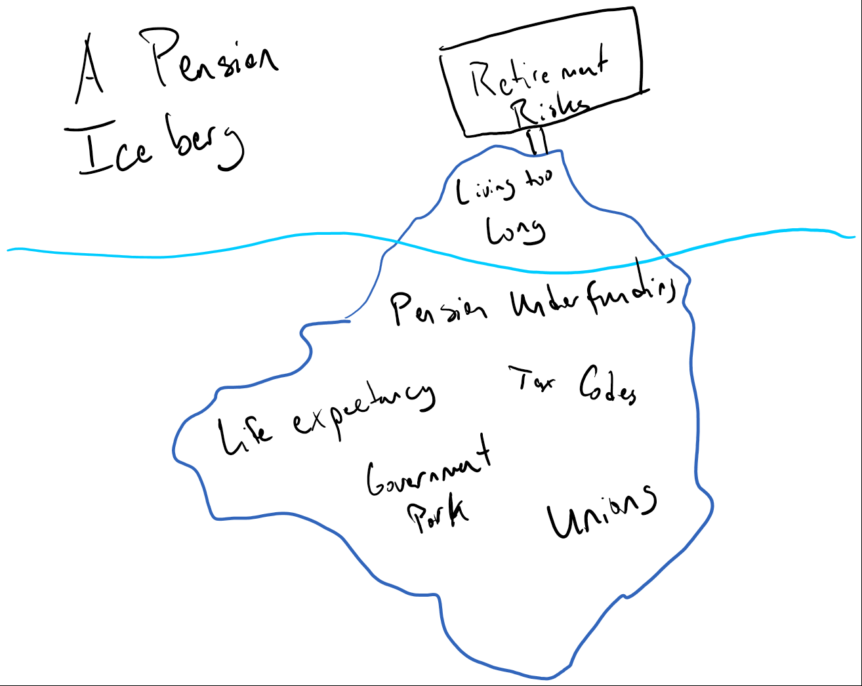

If social security sounds like a Ponzi scheme, it’s because to a certain extent, all traditional defined benefit and pension plans have an element of Ponzi-Esque nature to them. The contributions of younger employees are utilized to provide new funding for the plan, some of that funding is invested, and the rest goes out in the form of benefits. So long as the inflow is greater than the outflow, it’s more or less considered sustainable. However, if a couple of decades of concerns regarding social security’s funding haven’t made it clear: social security is not a bottomless pool of money. As far back as just about any financial planner can remember, clients have been asking: “But do you really think social security will be around for me?” So far it has, but in that regard, it’s actually a bit of a unicorn. There are enormous pension plans for unions, state employees, and private companies around the country, many of which are suffering significant benefits underfunding crises. In 2018, the Wall Street Journal reported that the cumulative shortfall of just the public pension systems in the United States was $4 trillion dollars in unfunded benefits, roughly the size of Germany’s annual gross domestic product (the 4th largest economy in the world.) The issues causing these shortfalls are legion. Americans are living longer on average than they did in the past so actuarial estimates are falling flat. Some public pension systems have restrictive limitations on their investment options by law, with the emphasis being placed on preserving the principal of the benefits trust rather than permitting them to grow sufficiently through investment returns to help fund future benefits. In some cases, it’s simply sloppy math or poor negotiation between unions and employing organizations, demanding benefits that cannot be afforded. Regardless of the individual cause of any individual pension’s shortfall, these costs are inevitably to be borne by the larger public, either in the form of taxpayer-funded bailouts, substantial reductions in promised benefits, or the simple collapse of pension benefits, leaving family members to support their financially devastated elders. To compound this, many public pension plans are considered “social security replacements”, meaning that employee tax dollars that would normally go into the social security trust are instead diverted to these localized state pension plans, many of which are underwater by billions of dollars, and sinking further every year. Not to panic you or anything like that.

The Elephant in the Room

Before we go on, we need to address something else first. The title of this piece invokes Animal Farm’s famous quote: “All animals are equal, but some are more equal than others”, the point being that in a system that supposes equality of opportunity and fairness, there is almost always going to be an exception to the rule. With regard to pension systems run by the government, it’s an unequal allowance of retirement savings and benefits. You see, the tax code and department of labor regulations, among other laws passed over the years, separate our retirement system into effectively three classes of employers. Government, medical/schools/religious/non-profit, and private employers; and that’s in order of best to worst options. This system provides a multitude of retirement plan options, some of which are only available to certain classes of employers. This includes commonly seen ones such as 401(k) plans and SIMPLE IRA plans, but in those more elevated organizations, you have options such as 403(b) plans for the middle class of organizations, requiring less compliance and oversight costs for the plan’s structure. At the governmental level, you get three of the best possible options: a pension plan replacement for social security (which is problematic for funding as we’ve discussed but permits an exciting “rebranding” of benefits), a 401(a) plan which combines the same principle as the pension plan replacement with a 401(k) plan, and a 457(b) plan. In the case of the 401(a), those same social security dollars go into a defined contribution account and are invested for the long term. In the case of 457(b), employees optionally defer compensation into the plan and their governmental employers may offer some form of match. Most notably, a 457(b) plan also receives the special reward of having a completely separate employee contribution limit from other plans. So while a part-time worker for two companies offering a 401(k) plan can only contribute a total of $19,500 to both of them in the aggregate, a part-time worker for the government with a 457(b) plan and any other form of defined contribution plan can contribute $19,500 to each plan, effectively doubling their potential tax savings and retirement deferral. And in a spectacular abuse of this whole system, you find private/public institutions such as state-funded hospitals, which may offer a social security replacement pension, 401(a) defined contribution plan, 403(b) plan, and a 401(k) plan all at the same time, which puts these institutions at an enormous competitive advantage against the free market because of the incredible amount of tax deferral permitted to highly compensated and sought after employees such as doctors. And just to rub salt in the wound, there are also plenty of small scale employers that cannot afford to provide retirement benefits for their employees or W2 “contractor agencies” that provide staffing for other companies that provide all of the work and wages but none of the benefits an employee of that company might receive. All of this to say: While the retirement plan landscape of the United States is supposed to be more or less equal, that we all participate in social security or a pension on some level and hopefully have access to a defined contribution plan through our employer, there are some institutions offering substantially greater benefits permitted by the imperfections of our regulatory framework, and others offering jack squat.

So What’s the Cure?

Well, let’s compare for a moment. Let’s say we have someone at the bottom of the economic scale. She starts a job at the federal minimum wage of $7.25 at the age of 18 and never earns a dollar more than that wage her whole life. She works a full 40 hours a week every week of every year (maybe there’s some paid vacation in there somewhere), and we’ll say that the offset of the fact that we’re not adjusting unknown future minimum wage increases into this model is that those hypothetical increases offset any job changes or stints of employment that occur; this is all being done to keep this analysis in “present value” so we can understand the value of the figures better. This hypothetical person is going to work 97,760 hours before they retire and is only going to earn $708,760 in that time (brutal, I know). But now let’s clone this hypothetical person into an alternate reality for a moment. Person A will contribute their 6.2% payroll tax into social security along with their employer’s 6.2% match. Person B will contribute the same amount into a 401(a) type defined contribution plan, with their investment options equally split into the five funds made available through the Federal Thrift Savings Plan (the completely free retirement plan and investment funds the Federal Government gives its employees), which has yielded a since inception weighted average of 7.46% per year. By the time Persons A and B reach age 65, Person A will be entitled to an annual social security benefit of $17,880 and have no liquid assets, while Person B will have a pool of assets equal to $801,150 and no social security. The kicker is that under the 4% distribution rule, Person B will be able to receive an income of $32,046 per year, adjusting for inflation annually. And the kicker here? If Person A dies young, their family and children will have nothing to show for it other than the potential for some survivor’s benefits. When Person B passes away, their family will inherit the balance of the 401(a) plan.

What about the Inequity?

Well, consider this for a moment. A large part of our national conversation regarding economic inequality between various groups revolves around net worth, the sum of assets owned minus the sum of liabilities owed. A key factor in this is the wealth passed down from generation to generation, and a key factor of that inheritance factor is life expectancy. In a country where life expectancy ranges from 75 years for Native Americans to 86 years for Asians, that amounts to a substantial difference in benefits received by a program such as social security. Further, while many employees of the government and other public entities receive pension benefits, some receiving far more than they ever contributed into the plan, they are often being left with little to pass onto their children. Conversely, professionals in high paying occupations or those who own businesses often utilize defined contribution and defined benefit plans to build up reserves of hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars in savings, which ultimately fund their retirement and pass onto their families upon their passing, along with the equity built out of private organizations they start or buy into through stock purchase plans and other acquisition tools. Ultimately, the great irony here is that while the government has given itself “bonus” retirement plans and resources, almost all of them have a fundamental failure: An inability to pass on wealth to others, while the limited retirement options available to private employers, specifically enable that objective despite the additional costs, layers of compliance, and limitations of those plans.

Comments 2

“. . . . employee tax dollars that would normally go into the social security trust are instead diverted to these localized state pension plans, many of which are underwater by billions of dollars, and sinking further every year. Not to panic you or anything like that.” Ha, ha, ha! Don’t panic??

Love these little tutorials but sadly only fully understand part of it – still, good information. Thanks

As always, a thorough and compelling analysis, Daniel! Thanks.