“It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer, or the baker that we expect our dinner, but from regard to their own interest.” Wrote Adam Smith in “The Wealth of Nations”, a classic treatise on what we now know as capitalism. As of late, a great deal of news and memes have been made up of the current labor shortage. With the jobs report in April reflecting only 1/4th the anticipated 1 million jobs filled, the media and public have been fraught. On one side, you have business owners pointing out that many of their businesses, small organizations paying lower wages, cannot compete with the high and extra unemployment benefits provided by the government in response to the pandemic. Others on the side of labor have pointed fingers that if unemployment wages are higher than earned wages, that’s simply an inditement on the greed of the business owners. However, from an economic vantage point, it’s not quite so simple. Today, we’re looking at the levels affecting this problem and will discuss the laws of unintended consequences in the subject of labor markets today.

Underwhelming Wages

Simply put, most people can agree that the minimum wage is not a living wage. While some would argue that “if you don’t die, it is by definition a living wage”, that’s sort of missing the point. Whether someone can feed themselves on their wages is certainly a bare qualification, but whether they can feed, house, and clothe themselves, let alone provide for a family or experience any of the joys that come with the human experience, is another. The push-pull of this is difficult to manage at a national level. While Colorado’s minimum wage of $12.32 is higher than most states and regions, even in Colorado it’s subjective. In Boulder County, the unofficial or proxy minimum wage is closer to $15 an hour. Any position offering less either goes unfilled or has an incredibly high turnover in employees. This de-facto minimum wage is a good example of labor markets doing what they should do: reflecting the living demands of the labor force in an unwillingness to accept work for less than what the market will bear. At the same time, in states that have only the federal minimum wage of $7.25 an hour, even a wage of $12.32 could seem enormously overpriced. All of this is ultimately a reflection of the local cost of living and the supply or demand for work, but where unemployment can offer a better time-for-money premium than the underwhelming wages of the free market, therein we will find problems.

Competing Against Unemployment

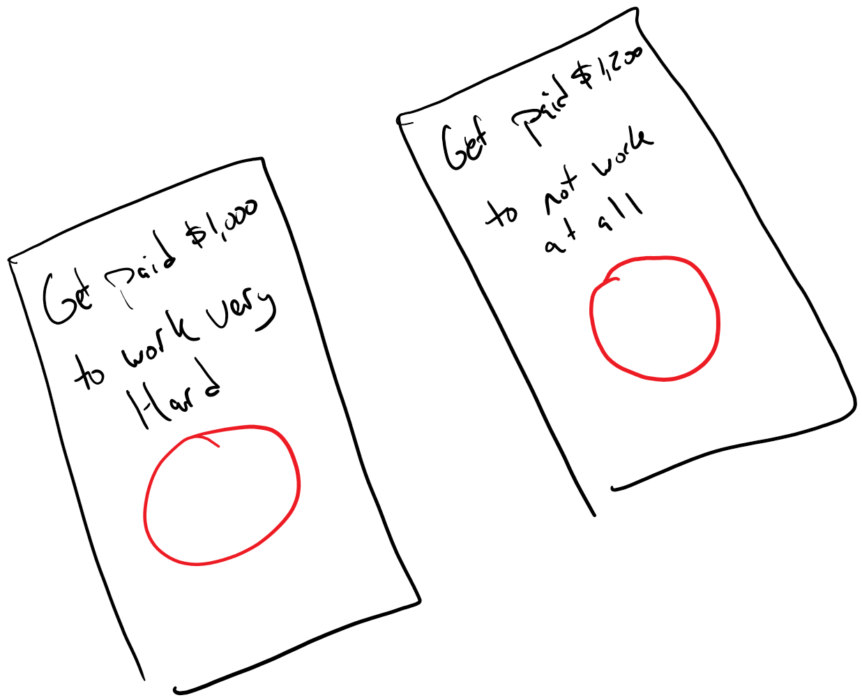

This contrast of minimalist $7.25 wages and de-facto $15 wages is important because the question of whether people are returning or will return to work heavily revolves around the unemployment stimulus, which has ranged from $600 per week to $300 per week. This means that in a month, an unemployed worker throughout the pandemic has theoretically been paid no less than $2,400 per month not to work, and has received even more based on the actual unemployment formula for their particular state. While that $2,400 is hardly more than what minimum wage would pay in Colorado, it’s a fairly decent wage to do nothing compared to working full 40 hour weeks in the midst of a pandemic. Even today with the federal stimulus reduced to $300 per week or $1,200 per month, it is effectively a multiple of earned wages with regard to “do nothing and get paid” or “do something and get paid moderately more”. When a small business and local employer is attempting to get someone to work for them, they are effectively facing an immediate hurdle so long as the federal stimulus is in place: “Can I work enough hours and make enough hourly to earn at least $1,200 per month? Or will a combination of working hours and the costs of commuting, childcare, and everything else leave me with less than that $1,200?” Now let me be the first to remind you: The bare minimums set by regulation are far from a quality wage, but this is a truly fair balance. There is no rational reason someone would go to work for a business if it is going to consume either a disproportionate amount of time relative to the time spent on unemployment or if for their labor they are going to net less income as a whole. And thus we run into an uncomfortable truth: Small businesses that rely on low-skill low-wage labor are in serious danger.

Big Box vs. Mom and Pop

At present, there is a national movement for a federal $15 an hour minimum wage, equal to the proxy minimum wage here in Longmont, CO, and Boulder county as a whole. This movement is heavily endorsed not by small businesses but by big businesses, the Targets and Walmarts of the world. Why? Because they already pay the de facto minimum wage of $15 an hour. While it was a fairly recent development for some, a large organization with significant economies of scale and well-established discounted supply chains can afford to squeeze its margins tighter by increasing its labor costs. While the local superstore might run an average of $150,000 to $200,000 in revenue a day at a 30% margin, that could easily be the equivalent of an entire month of revenue or even several months of revenue to a mom-and-pop retail shop. Even though that superstore will have higher utility costs and significantly higher labor costs, it still has a larger dollar margin to leverage when it needs to. This is on top of static benefit costs that as a ratio of labor costs can be significantly smaller as a big box store, such as the static cost of healthcare or retirement plan benefits that may be entirely out of pocket to the employees. Thus, while the national conversation regarding whether businesses paying less than the unemployment benefits are even paying fair wages is a reasonable one, it certainly misses the competitive landscape. For all our national hemming and hawing about whether the United States is a democracy or a plutocracy, we’re quick to shout down objections to governmentally imposed systems that put small and independent businesses at a disadvantage.

Long Term Outcomes

The pandemic taught us a lesson about essential workers. For the hour of a professional’s time at $300, up to twenty grocery store workers could be risking their health and welfare to ensure we have food to eat. For every cashier at a store or server at a restaurant, we potentially miss the point that fractional margins of the wages earned by some equate to more than the whole of wages earned by several or even dozens of others. This has traditionally reflected the “value” of the time and expertise of the workers. After all, anyone with the physical ability can put boxes on a shelf or carry a drink to a patron, but how many people can perform brain surgery or put rockets into space? Yet, in a labor market where suddenly a competitor with theoretically limitless resources comes to play (the government), we suddenly see a shift from the price of labor being based on the unique value it can deliver, and a pressure is introduced that reflects non-market forces: a de-facto “minimum un-working wage” that threatens the free market. Was the free market working perfectly before the pandemic? Certainly not. But at the same time, without the pressure of a de-facto minimum wage to create competition for good employees, businesses will either cease to function or will offer only what they can, reflective of the value of the labor and not necessarily the costs it demands. Some businesses have addressed this head-on. Over the weekend I ate at Tangerine, a local breakfast place, and found a 7% “business survival charge” on the ticket at the end, reflecting the fact that costs have simply gone up. Is this greed on the part of the owners? No, it is simply a small business attempting to account for the costs that a market experiencing turmoil and an intrusion by anti-competitive forces has brought to it. Will these forces eventually normalize? We can only hope, but for now, expect that things simply are and shall be more expensive until the labor markets can turn to a new normal.

Comments 4

Wow! A lot of food for thought here.

Aunt Alice’s Restaurant is charging a $3.99 surcharge for using a credit card instead of paying cash. It is their way of surviving. I pay cash now and rarely go there.

There is a price to pay for raising prices – we consumers buy less, eat out less. We go to places like Amazon & Costco for a competitive price on goods because we don’t suddenly have more money to help small businesses survive.

This feels like a downward spiral . . . hummm.

The Our Center here in Longmont is providing food and money for rent etc. for those who are pinched. I work there and we feed lots and lots of people and the food is first rate. I can’t afford the upscale produce that we give freely. Why should they go to work? If they do, they won’t eat as well, LOL.

Nicely done Dan…..as always

Nicely done again Dan…..as always

Who knew Daniel Yerger was an economist?! Well, I did, actually, but this is a very important and cogent analysis. I might quibble with the term “anticompetitive”; but that would obscure the much more important point about unintended consequences. Would love to explore how policies could better adjust for unintended consequences.

Thanks for improving the quality of our public discourse!

Jim