It’s not uncommon that we see a headline such as: “Elon Musk made $36 billion dollars in yesterday’s Tesla surge.” The grammar of such a statement leads us to believe that the profits of Tesla were so substantial that Elon Musk was given a check for $36 billion. However, that’s not really the case. While $36 billion is an incomprehensible amount of money for any individual to have, what has really happened is that the value of Tesla stock increased so much that Elon Musk’s shares grew in value by $36 billion. That might seem like a distinction without a difference, but that distinction is at the heart of much of the debates over wealth inequality and taxes in the United States. Last week, with Democratic intransigents Senators Manchin and Sinema continuing to block the $3.5 trillion social safety net and infrastructure package, Treasury Secretary Yellen proposed a change to the tax rates within the bill, including the creation of a special income tax for those with a net worth greater than $1 billion or an income of greater than $100 million for three years or more. Today, we’re going to dig into how income taxes work to explain how this idea functions and what it would mean for everyday taxpayers like us.

How Income Tax Works

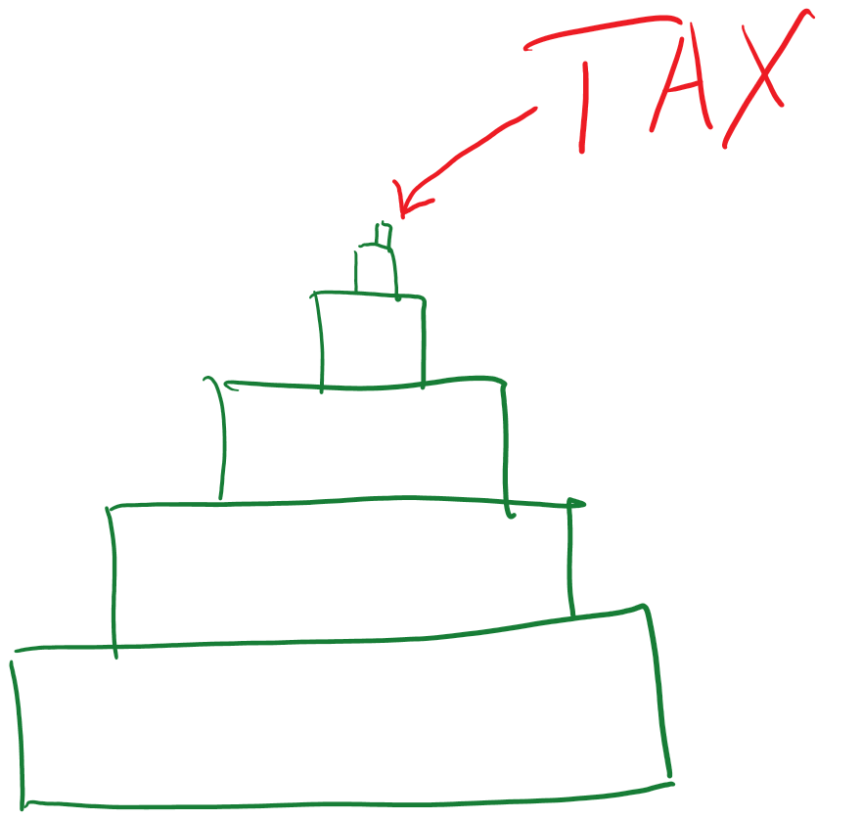

First things first, a discussion of income tax has to include a clear definition of what that is. Taxes in the United States historically were consumption taxes (i.e., sales tax) until the 16th Amendment to the Constitution was passed in 1905, making it constitutional to tax the income of individuals and businesses directly. Our income tax is, despite the political cries of those on both sides of the aisle, one of the most progressive income tax systems in the world. A progressive income tax increases with the level of income, meaning that those who earn more pay more and those who earn less pay less. This contrasts with a flat tax, which while arguably more “fair,” is considered regressive as those with low income can afford less of their income going to taxes than those who earn more. All that to say, our income tax system uses a marginal brackets system. In simple terms, income between various points is taxed at different levels. Right out of the gate, a single person gets the first $12,550 of their income tax free. Past that point, the next $9,950 dollars are taxed at 10%, then the next $30,574 dollars are taxed at 12%, and so on until those single people earning more than $523,601 per year are taxed 37% in federal income tax. On top of this, many states levy an income tax; for example, in Colorado, that income tax is 4.55%, so that a person earning $523,601 is paying 41.55% in income taxes between the federal and state rates on their dollars earned over $523,601, and less on dollars before that point. Notably, we have different tax rates for investments, which are termed capital gains. Different than income, capital gains (or losses) are realized when a piece of property is sold at a profit or a loss. If it is sold within less than a year of ownership, it uses the income tax rates for earned income as we just discussed, and if it’s sold after longer than a year, it uses a special set of rates which include 0%, 15%, and 20%. There are thousands of special rules around the sale of property and the taxation of property, including 1031 like-kind exchanges, the tax reduction for the sale of a personal residence, the wash sale rule on securities, and so on. Succinctly in this area of the tax code, the most important factor is the deferral of taxation on assets. It doesn’t matter how little something was worth when you bought it or how valuable it has become; it is only taxed at the point at which you sell it for a profit, or you receive a writeoff if you sell it at a loss. This means ownership of things such as your home, collections, the value of your business, and so on, are not taxed until they are converted from property into cash. This also means you are not taxed as the value of your home increases (plus or minus your property tax assessments, but not capital gains on the appreciation), or as the value of your assets decreases.

Recent Tax Changes

The most significant change to taxes occurred in December of 2017 when the “Tax Cuts and Jobs Act” passed on entirely party lines through both the house and senate. In concept, the TCJA “simplified” the tax code, bringing brackets for single people, heads of household, and married couples into a “multiples” alignment so that there was no premium or penalty for being married or single, along with many changes such as tweaks to how business income is taxed and what types of expenses are deductible. Significantly, this major tax change omitted changes to the “carried interest” rule, which creates a special tax class for the general partners of a private investment fund (read: hedge fund managers), taxing income they earned as the general partner of the fund as capital gains instead of earned income. If you had to single out a particular part of the tax code as “unfairly favoring the rich,” this would be your best candidate. But notably, despite the fact that this has saved hundreds of millions in taxes for hedge fund managers, this is not the loophole that most billionaires are looking for. While reports such as the Panama and Pandora papers do shed a light on the aggressive use of attorneys and accountants to shelter as much income from taxation as possible, the primary tool at the disposal of billionaires to avoid taxation is how capital gains tax works as we already discussed, and the use of loans. Last year, former President Trump’s tax returns were leaked and revealed that he, like many ultra-wealthy, uses debt to finance his lifestyle rather than earned income. By borrowing heavily against his family’s substantial assets, he uses that debt as spending money while realizing nominal capital gains or actual income from his work to pay the interest, and otherwise uses capital losses as deductions or write-offs against future income. This is all possible because, just as for the rest of us, taking a loan from the bank is not treated as income, because ultimately we will have to pay it back with some form of income and with interest. The simple tool of having assets to borrow against while using highly appreciated and appreciating assets as collateral through the capital gains system is at the crux of stories wherein billionaires pay little to no income tax.

The Billionaire’s Tax and You

Notably, a “wealth tax” is unconstitutional at present. While a highly divided Congress and country are unlikely to amend the constitution to make it constitutional, a definitional trick is at the heart of the proposed billionaire’s tax: To redefine assets over $1 billion and income over $100 million as income; simply put, reclassifying those with enormous wealth and high income as receiving an income from the appreciation of their assets even though they don’t. While this sounds dubious or tricky, it’s fully permitted under the constitution as written, and in doing so, we could see a substantial redistribution of assets from those billionaires; an argument of “trickle-down economics” (which is a political term not used by those who support the underlying mechanisms) has always been that those with high income and assets will spend a lot of money, thereby creating jobs and economic opportunities for others. In effect, the billionaire’s tax would force that behavior, as billionaires would be faced with a choice to either spend and donate their money or simply hand it over to the government. This is a proposal that, for a rare first time, effectively targets the ultra-wealthy in the country rather than the merely affluent. That’s not to say that those earning in the top tax brackets of the United States aren’t doing very well compared to the average American, but that historically tax proposals aimed at “taxing the rich” have sat a substantial tax burden on the top 9% to 2% of those in the country, not the top 1% because it has always focused on the taxation of high income, not appreciated assets or changes to capital gains. If this measure is included in the bills in consideration or is pushed through at some point in lieu of the $3.5 trillion bills increases to marginal tax rates, this would be the first time that the ultra-wealthy are actually effectively targeted for taxation rather than targeting the broader public. Will it go through? We’ll see, but it’s an interesting and novel attempt for sure, and it doesn’t come out of your pocket or mine, at least for now.

Comments 1

Excellent! I get it! Let’s hope that “Billionaire’s tax” is passed. Being “wealthy” is ok but there is an upper limit beyond which no one can use all that money.