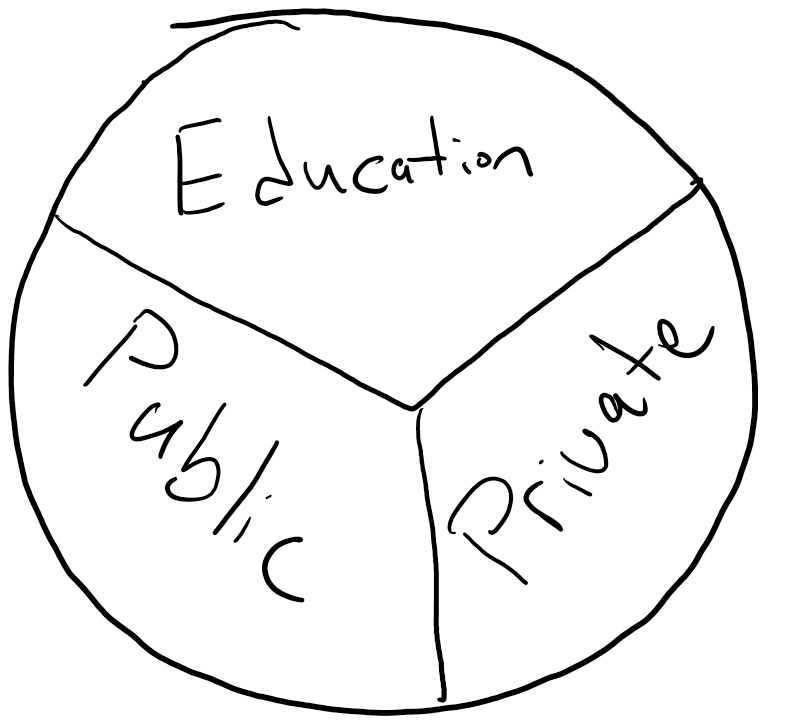

As paradoxical as it seems, the wealth gap is not increasing in the United States. Not in any meaningful way, at least. While not a month passes that we don’t hear about a billionaire who barely paid any taxes, or another that has accrued billions in a tax-free account, the fact of the matter is that wealth in the United States when placed on a bell curve has a substantial positive skew. Stated differently, it means that the positive wealth extremes extend enormously beyond the range most people live in. This is often held up as evidence of inequity, but I would argue it’s only evidence of inequality, and not of a bad kind. To be clear, this week we’re not writing a piece on defending billionaires, but simply starting the piece by suggesting that they just simply shouldn’t matter that much to you. Rather, we’re going to focus on three often neglected areas of wealth-building that are open to just about everyone, should they decide to use them.

Human Capital

The traditional American path since world war two has been to graduate high school and attend college. While only about half the population actually ends up attending college and only a third graduates, this has been the ethos for over eighty years, largely fueled by the GI Bill. There are two major theories that suggest “why” we go to college (or trade schools or build up skills of any significant kind.) The first is signaling theory, which suggests that it’s not the skills or knowledge gained in college, but our ability to signal to partners and employers that we have graduated with a degree from college, and therefore we are more suitable to the work they might offer us than others who haven’t. One might call this the “cynic’s” view of education. The other is a bit more to the point and likely follows how you’ve thought of college: that you are making an investment now (tuition and time) to increase your future earning power, and the evidence supports this. In 2015, Christopher Tamorini and a research team published that the average high school graduate was likely to earn a cumulative $1.53 million dollars, while someone with a bachelor’s was likely to earn $2.19 million, and those with graduate degrees would earn $2.68 million. Notably, however, there was a dramatic skew between men and women, who earned $870 thousand if only a high school graduate, $1.32 million with a bachelor’s, and $1.69 million with graduate degrees. While someone might be quick to leap up and shout that this is gender discrimination, it materially reflects two important decisions: first, that the degrees taken matter. To date, men still occupy higher-earning degree fields such as STEM at a higher rate than women, while women occupy more of the social sciences, and which have dramatically different earning potential. Second, that women are unfairly burdened with the physical act of bearing children, and are often unfairly burdened with child-raising; at least at a disproportionate rate to men. Consequently, both the decision to study something with higher or lower earning potential and the decisions made further along in life can call into question the value orAl lack of value from paying for an education. We’ll of course also close the education point on the note that you shouldn’t overpay for education. If your intention is to be a philosopher, there is no particularly good argument for paying to attend an Ivy League school.

Public Markets

In the study of behavioral finance, there’s a concept called “the stockholding puzzle.” Described simply, the material observation is that the largest and most consistent driver of wealth over the past century has been ownership of publicly traded stocks, yet despite this well-established fact, only about half of the population directly invests in the market. This ratio gets a bit squirmy because of things like pension plans, which invest in the market on participants’ behalf, but the observation is still critical. For example, a young graduate who goes to work as a teacher for a school district will often be placed in a pension plan. The graduate will pay a large percentage of their wages into the district’s pension plan and in return, based on the number of years worked and the specific age they retire at, they’ll receive an annuity-based stream of income. Yet, that graduate is not the primary beneficiary of this structure. For example, if the graduate starts at 22 and “quits” at 42, with 20 years of service, they will be kept from drawing on the pension for possibly well over a decade. Another teacher who comes along and starts working at 42 and retires at 62, can immediately draw on their income, despite relatively equal working histories and careers. The young graduate is subsidizing the pensions of the older employees as they retire. Meanwhile, that graduate’s peers working in the private sector are likely contributing to defined contribution plans, which favor younger employees because of the time given to them for their savings and investments to compound. The argument between the two models is one of “risk management,” that the teachers supposedly don’t want to assume risks and the private employees somehow do. Yet the financial outcomes are staggeringly different because the pension will likely never show up in a report of “net worth,” while the defined contribution plan’s account balance almost certainly will. Not to mention, the pension is investing in the stock market and taking on market risks. It’s simply doing so in a way that makes the pensioners feel safe when there is, in fact, no more safety in the pension plan than there is for the market investors.

Private Markets

In the seminal work, “The Millionaire Next Door,” the researchers identified numerous consistent and common traits of millionaires in our society. One of the key standouts was that the majority of millionaires in their study were business owners. This is not surprising at all, because a private business is arguably one of the highest risk assets possible. With four out of five businesses failing in the first five years, a natural aggregation of the value of existing businesses (supply chains, customer relationships, repeat customers, etc.) occurs, which ultimately increases their values. Of course, while black swan events such as the pandemic can derail even successful businesses, the ownership of private assets can represent an enormously valuable asset. Another item to consider is the safety and control of the income provided by a private business versus a job. While a paycheck may show up every two weeks for many who are employed by larger businesses, their jobs and careers are always exposed to the whims of the next manager change, merger, or business crisis. While the same is true of a private business, there is still one advantage: an employee has one customer (their employer) while a private business likely has dozens, hundreds, or thousands. None of this is to say a business isn’t without risk, but a career with any organization or company does carry the risk of putting all income potential in one basket.

Dr. Daniel M. Yerger is the President of MY Wealth Planners®, a fee-only financial planning firm serving Longmont, CO’s accomplished professionals.

Comments 2

Thank you for this post! I totally agree that another zero for a billionaire is not something to compare myself to or punish that individual for.

Is there a slight bias towards owning your own business running through your essays? I wonder why? (smile). Still, lots of good information here. Thanks