It never fails that investing lives in a perpetual Schrodinger’s Box of reputation. Investments simultaneously are too risky and also the reason billionaires exist. The market is equally “overpriced” and also “losing too much to buy into right now.” Cash is “safe” yet loses a guaranteed percentage of its value every year. On and on, the paradoxes of an investment grip our attention in the financial world, causing us both elation and dread with every passing news headline. Yet, despite the short-term noise, the long-term data is clear: investment over a long duration (years, not months or days) is a largely profitable enterprise. That’s not to say all investments do well -as many do not- but that while a diverse collection of investments will have some losers, it will likely be largely made up of long-term winners. Today we’re talking about some of the tenants of effective long-term investing, and why they should matter to you.

Time Horizon

Einstein famously said that “compounding interest is the 8th wonder of the world.” While this is inarguably true (I’m a financial planner, of course, I think it’s a wonder), a key component of how compounding works is time. It is not simply instantaneous mathematical repetition that drives compounding, but also the measure of time over which compounding math actually functions. While technically nothing stops compounding from being near-instantaneous, it’s a practical requirement that businesses have to operate, grow margins and profits, create value, and in turn create more value for the shareholding investors like you for compounding to actually take place. In turn, this means that shorter investment time horizons are more heavily reliant on the “windfall” of markets to provide a return or otherwise end up being more exposed to the market environment. For example, you can see below the odds over the past 100 years that while the long-term return of an index such as the Dow Jones Industrial has been mathematically all but guaranteed, the short-term has carried greater risk.

|

Rolling Time Period |

Range of Annual Returns |

Percentage of Time Periods with a Negative Return |

| 1 Year | -43.3% – 54% |

26.3% |

|

2 Years |

-34.8% – 41.7% |

17% |

|

3 Years |

-27% – 31.2% |

16.1% |

|

5 Years |

-12.5% – 28.6% |

13.2% |

|

10 Years |

-1.4% – 20.1% |

4.7% |

|

15 Years |

0.6% – 18.9% |

0% |

|

20 Years |

3.1% – 17.9% |

0% |

|

25 Years |

5.9% – 17.2% |

0% |

|

30 Years |

8.5% – 13.7% |

0% |

Rolling performance of the Dow Jones Industrial Average since inception.

Allocating Before the Drop

The simple math of the matter is that diversification and proper asset allocation can only remove about 30% of the risk in your portfolio. This is called “non-systematic risk,” which comes from being overconcentrated in too few companies or investments, and the concentration of risks that can come with being overly exposed to a single or few companies. When the portfolio has been diversified to at least 24 investments (let alone hundreds or thousands provided by a broad index fund,) the portfolio now is “only” exposed to the other 70% of the risk, which is systematic risk. This is “the marketplace” in the true sense, where things like wars, taxes, politics, and general public sentiment come into play. There is no way to dodge this risk except in one way: to overconcentrate, take back on non-systematic risk, and hope that your crystal ball works well enough to avoid the scandal or market conditions that might ruin you. Most people don’t have the guts to do so, and frankly, no one has the crystal ball to do so. So ultimately, what the research has shown us for decades, is that allocating conservatively or aggressively to begin with is the best consideration of how you then want to be invested during the downturn. Being aggressive during a growth period will net the highest returns, but also the roughest and sharpest drop when the markets turn sour. In turn, even a conservative portfolio in the markets is still exposed to the systematic risk of the markets. This means that an aggressive investor must be comfortable with volatility, and even a conservative investor must be comfortable with some, albeit less, volatility.

Harvesting During the Drop

While selling out of the portfolio or “running to safety” during a downturn is functionally pointless (it’s like trying to un-wreck your car after the crash), this doesn’t mean that all is lost. Downturns become excellent times for investors with non-retirement accounts to harvest tax losses and gains to offset each other, raising the “cost basis” of a portfolio and reducing their current and future taxation by netting out the gains and losses against each other while still staying invested. For one client, this strategy has allowed us to “update” the cost basis in over $200,000 of assets this year, meaning that that same $200,000 later sold will not carry such a significant tax burden as it might had we let it sit still. The word of warning in tax-loss harvesting is the wash sale rule: identical or substantially similar securities bought and sold in a 30-day window are considered “canceled” for tax purposes as if the sales and purchases never happened. So you can’t merely jump in and out of the harvest quickly, you’ve got to have an eye on the next few months for it to be effective.

Guardrails for Income

For those already in retirement, “long-term investing” can seem more like a threat than a promise. After all, it’s hard to focus on the long-term market environment when you’re seeing your balance decline! However, there is some exciting new research on this front. Well known (by financial planners) researchers including Dr. Derek Tharp of the University of Southern Maine, Dr. David Blanchett of Morningstar, and Dr. Wade Pfau of The American College have all completed multiple experiments and studies around the use of “guard rails” in retirement as both a psychological framing strategy and income distribution strategy. The idea is that instead of setting an annual income level in retirement and then following it with adjustments for inflation only, the income can be flat within a certain band of portfolio returns until it either hits the top or bottom of the band. If it hits the top, income can increase. If it hits the bottom, income has to decrease. This can feel riskier to a retiree because we’re used to having a stable paycheck, but the results are incredible, with retirement plans structured this way using data going back to 1891 (that’s not a typo!) showing that retirement plans with as low as 20% Monte Carlo probability (meaning 800 scenarios would fail) show almost identical income levels to plans with as high as a 90% confidence level. The key in this strategy when thinking about long-term investing is that the investor has to be comfortable with having “boom and bust” income years from their portfolio.

Holding the Course

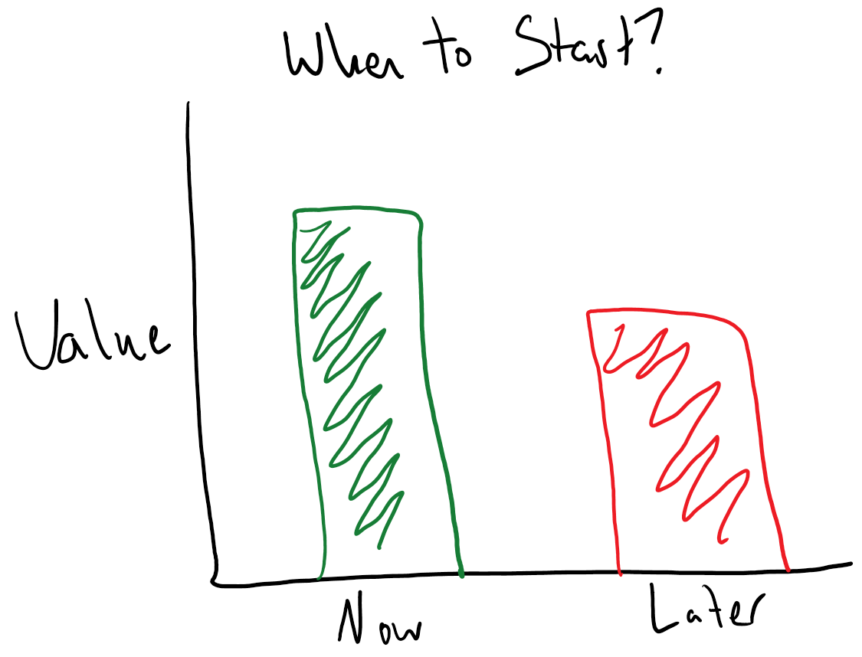

Ultimately, the key to long-term investing is that you invest. For the long term. For those with short-term goals, investing can feel more like gambling or speculation, and the math does hold that up. I personally live the research, choosing to invest money for the long term at all times, and otherwise trying to preserve cash for the short term. My personal goals and point in life are different from just about everyone else’s, but the point here is that you can choose to do that which is well researched, valid, and keep the long term viewpoint, or get sucked into the minutiae of the current news environment shouting catastrophe from every corner. It turns out, catastrophes in the market tend to be short-lived, and for the patient, they’re great opportunities.

Dr. Daniel M. Yerger is the President of MY Wealth Planners®, a fee-only financial planning firm serving Longmont, CO’s accomplished professionals.

Comments 1

“Schrodinger’s Box”!! I love it. What an apt description. It appears that the “guard rail” approach to retirement income is a good one. Just wondering what my retirement approach is called. I think I want the “guard rail” one. LOL

P