Here’s a simple experiment: The next time you buy any good or service that isn’t clearly labeled with its price, ask what it costs. For example, if you go to a high-end restaurant and they list cocktails without prices, ask the server what it costs. They will likely know immediately or be able to check out the price quickly on a point-of-sale system and tell you. Do the same at your mechanic’s. “What will this repair cost me?” They may not have the exact figure, but they can probably provide an estimate of labor hours, look up the price of the parts they think they’ll need, and give you a reasonable estimate, assuming that they don’t discover other issues that create scope creep from the original request. Now do the same thing with your doctor at a checkup. Watch as they say they can’t be sure, indicate that you’d have to ask your insurance company and make zero effort to obtain an estimate of the price for their services. If you really grill one, they might be willing to share their normal reimbursement rate for the specialization they serve, but many will have little to no idea what the cost of their services is. So why the difference between this one select profession and essentially every other one? Well, because it turns out, that there’s a lot of money in medicine, but there isn’t a lot of transparency. Today, we’re discussing how the cost of healthcare has gotten so outrageous over the years, why no one seems to know the cost of anything, and how you can fight the high cost of both normal and surprise medical expenses.

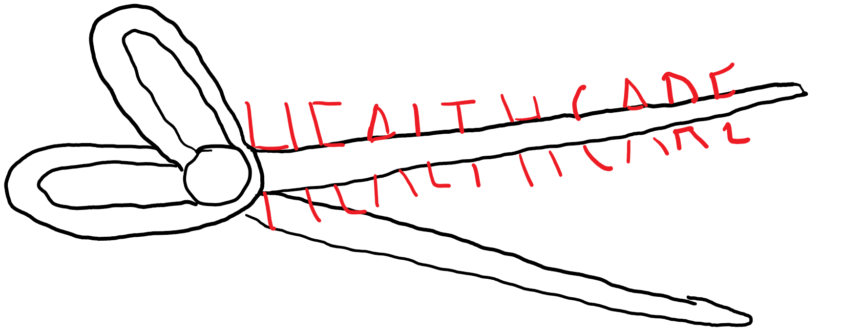

The High Cost of Healthcare

Prior to 1929, healthcare was a singularly individual transaction. You’d wake up with a cough, pick up the phone, call your town doctor, and he (almost always he, in those days) would come to your home, perform the necessary diagnostic tests, and give you a diagnosis and a course of treatment. This service might be expensive, akin to the cost of paying for an attorney’s time, but it was predictable and straightforward. This arrangement began to change over the years for a few reasons: First, lower-income individuals potentially couldn’t afford even the predictable high cost of that visit, and so decided to band together to form risk pools. The first employer-based health insurance contract was created in 1929 by school teachers in Dallas, which guaranteed affordable care at a single hospital in the district. In 1945, an entrepreneurial surgeon saw the regular injuries and ailments befalling the thousands of laborers working on the Colorado River Aqueduct and opened a hospital nearby, further establishing a “prepayment” system where the laborers could pay a nickel a day and be guaranteed care at the hospital for their ailments. These ideas gained further traction as computers began to take shape during World War Two and beyond, providing us with the technology to create advanced screening systems and tools. However, many of these tools such as MRIs and dialysis machines were expensive to build, maintain, non-portable, and in short supply. As a result, the cost of healthcare continued to climb due to the disproportionate supply and demand. As that original hospital coverage deal in 1929 grew into Blue Cross Blue Shield a steadily growing leviathan industry of administration, billing specialists, and consultants grew out of the original Doctor-Patient relationship, ultimately creating the labyrinthine monstrosity we now call American healthcare. The issues therein have also been compounded further by a gross undersupply-to-demand ratio. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education, an association of physician’s organizations, sets the number of medical school seats and medical residencies each year, effectively using the healthcare industry’s control over accreditation and licensing to choke off the supply of doctors and reduce competition within their own profession. The defense of this course of action has always been argued as being a focus on the quality of candidates and medical professionals (after all, who wants a “low quality” doctor?) However, this somewhat misses the point. The national acceptance rate for Medical Schools is 43% for those with an undergraduate GPA of 3.6 or higher; not only does this mean that the median “A-” is not going to be accepted to a medical school, but that even an above average student is statistically unlikely to gain entry. Ultimately then, we see a compounding effect in the healthcare world: An undersupply of doctors that grows in a slow and almost linear fashion, compared to the exponential growth of demand in the population, compounded by decades of incumbent healthcare administration infrastructure and billions of dollars in vested self-interest by those organizations and entities.

Why No One Knows the Cost

If the word “complexity” doesn’t sum it up, it’s perhaps better summed up as a bad game of anchoring. Anchoring is the behavioral finance term for being overly attached to the first data point in consideration of the second data point. For example, if you’re applying for a job and the employer says the salary is $60,000, but you really wanted $70,000, you now have to overcome your and their bias that all pushes towards $70,000 are “asks for more.” Conversely, if you had said your salary expectation was $70,000 and they only wanted to pay you $60,000, then all of their pushes toward $60,000 would be asking you to take less than desired. Same data points, but the framing impacts our understanding. So how does anchoring apply to healthcare? Well, as the insurance industry has grown and grown, hospitals and medical providers have been put in a tough position. When most of the healthcare purchasing power in the country is vested in a handful of medical insurance companies, very few medical providers are in networks of consummate size with proportionate negotiating power. This means that to counteract the aggressive oligopoly of insurance carriers, medical service providers set “hail mary” prices for everything from heart surgery to Asprin. In the 2013 Times Magazine expose, “Bitter Pill,” the reporters discovered that some subjects followed through their healthcare journey paid enormously different prices for the same services, including $13.94 for a blood test paid for by medicare while another paid $199 at the same hospital through private insurance and $239 at another hospital nearby. Other examples abounded in the article: $39 for a surgeon’s gown that cost $5-a-piece when bought in bulk, $32 to use a blanket, $31 to click a strap into place on a gurney, and even $1.50 for a single 325mg tablet of Tylenol that could be bought for $0.08 per tablet off the shelf in a Walgreens, let alone with the bulk purchasing power of a hospital. A study was even conducted to figure out the real cost of arthroscopic knee surgery. The result? While a hospital in Milwaukee was charging an average of $21,635 per procedure, the actual cost (adding up the surgeon’s time, nurse’s time, anesthetist’s time, physical therapist’s time, materials, components, etc.) was closer to $14,257. While a 51.7% margin doesn’t seem like a lot, we have to remember that it would be a pure profit margin after the costs of already highly paid professional surgeons and other staff was accounted for. Even in light of a law that took effect in 2021 requiring hospitals to make their prices for services and procedures publicly available, many institutions are simply not complying with the requirement, while others have deliberately buried and hidden their pricing behind pages of deliberately difficult-to-navigate websites. Simply put: not only are hospitals overcharging insurance companies in order to get more acceptable negotiated rates, but the prices have such a nominal relationship with the actual cost of the service, that it’s effectively impossible for even the professionals providing the services to give a reasonable estimate of the costs.

Reducing the Cost of YOUR Healthcare

Given such a frustratingly arcane system of expenses, lack of transparency, and the willful ignorance of all parties involved, how can you reduce your cost of healthcare? First, let’s consider whether it’s a planned expense or not. If you are thinking about something like a surgery that you might need within the next year or two, a major step is to upgrade your health insurance. Health insurance typically lives on a spectrum of “pay more now, pay less later” or “Pay less now, pay more later.” Effectively, the higher your premiums, the less you’ll need to pay at the point of care, and vice versa. If you’re anticipating a major expense such as surgery, you should attempt to reduce your deductibles and out-of-pocket maximums as much as you can with the offset being higher premiums during the year of service. Still, paying $5,000 a year for “Cadillac” insurance with no deductible is going to be a lot more affordable than paying $2,400 for catastrophic insurance that then also costs $7,000 for the deductible. Next, shop the cost of care. That might seem silly, but remember that it is a federal law that hospitals and major medical providers disclose their costs publicly. If you have the time and energy to seek out a healthcare provider with more reasonable costs that’s in-network for your health insurance, you might find that you end up with a lower out-of-pocket cost as well. For those without insurance, the same factor applies, as does asking “at the point of sale.” Asking for a fixed cost before agreeing to a procedure is possible with some healthcare providers, and many will accept a better-negotiated cash rate than the assumed “shelf price” that is charged to insurers.

What about the cases where you can’t plan ahead for the expense, such as an emergency medical procedure? While you’re stuck with getting the care given to you when you’re in immediate crisis or incapacitated, you’re not obligated to make a payment for services immediately upon receiving the bill. Requesting an itemized medical bill has been shown to reduce the average cost of medical care substantially. This is possible for a few reasons: First, you gain the opportunity to identify medical expenses you didn’t incur (i.e. specialists who never worked on you, tracking errors, duplicate expenses, etc.) Second, you can compare the costs you’re expected to pay directly and compare them to your insurance; it is not uncommon for medical billing specialists and insurance specialists to make errors in the application of your coverage to the bill, and as a result, you may find expenses that your insurance isn’t paying for or isn’t paying the correct amount for. Finally, you can make an offer that’s alternative to the billing codes the medical provider is suggesting. Many hospitals have hundreds of thousands of dollars if not millions of dollars in write-offs annually for services that they never end up being paid for, often selling those bills to collections agencies at pennies on the dollar. Negotiating or offering to pay as little as 50%-70% of the final bill might surprisingly be accepted, as the alternative to the hospital might be selling your bill at 1% of the billing value to a collector. Finally, for those in Colorado, get your quote for services upfront. This year the Colorado Supreme Court found in French v. Centura Health Corporation that the patient (French) was not liable for more than the fees she was quoted before her procedure, due to an error on the part of the Century Health billing specialist who quoted her inaccurate costs and would have left her with over two hundred thousand dollars in medical expenses rather than the few hundred dollars she had agreed to upfront. If you are confronted with substantially higher costs than those quoted due to an error, you may wish to consult legal counsel about appealing based on this precedent.