Financial planning is a profession that has grown out of the traditions of several others: amalgamating segments of knowledge from attorneys, CPAs, stock brokers, insurance agents, economists, psychologists, and traditional institutional finance, financial planning draws from many fields and pulls in many resources and theories in its practice. In my own pursuit of a Ph.D. in Personal Financial Planning, I’ve become quite familiar with many of the underlying academic theories that inform the practice of financial planning. Today, I’m sharing a summary of some of the major theories and how they interact with the public when engaging financial planners and in financial planning.

Life Cycle Hypothesis & The Behavioral Life Cycle Hypothesis

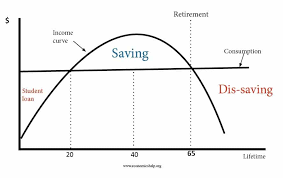

Back in the 60s, it became apparent that human beings engage in a fairly consistent cycle of behavior in modern society: We incur debts early in life to help us reach a certain threshold of life quality, such as student loans for education and mortgages for homes. At a certain point, income increases enough such that we have excess income over our expenses, which we then save for the long term. When we get older, we stop having an income and live on excess savings (retirement) and pass away with little to no money left. This theory fills in a nice arch diagram like the one below:

The theory does have some limitations, however, because it makes a particularly specific set of assumptions about people that don’t really hold up in reality: That people are rational and attempting to maximize the utility in their lives, that they can solve the financial optimization problem that the hypothesis suggests and that they will have sufficient willpower to execute “the plan” the hypothesis suggests. Do you see the problem here?

Enter the Behavioral Life Cycle Hypothesis, which brings human nature into the equation. Rather than assuming people are rational and will maximize their financial outcomes by default, it assumes that people will make mistakes and value things incorrectly. More importantly, it acknowledges certain behavioral biases, such as our willingness to spend income but not to sell assets to fund expenses, and that financial self-control can vary from time to time and circumstance to circumstance.

How this interacts with clients: If the life cycle hypothesis were true of everyone, there would be no need for financial planners. Each individual household would accurately assess their lifetime financial needs and execute a self-developed plan to maximize their financial outcomes. Given the high demand for financial planners, social issues such as underfunded retirement savings, and enormous and untenable debt burdens faced by many people, it’s quite clear that the non-behavioral hypothesis doesn’t stand up. Yet, the behavioral hypothesis highlights many of the needs that lead people to seek financial planning help, including an inability to calculate or plan for financial needs, help with optimizing financial behavior, and placing constraints on financial behavior so as not to underfund future financial needs.

Economics of Information

In the 60s and 70s, a theory came into formation known as “the economics of information.” While traditional economic theory makes a common assumption that people are rational and act with perfect information about their financial choices most of the time, the economics of information sought to address one particular issue: The fact that information asymmetries exist between buyers and sellers of goods and services all the time. The classic example in this theory is “used cars” or “avoidance of lemons.” The second seminal paper on the subject by George Akerlof highlights that the low price of used cars and the high price of new cars in comparison is not a reflection that new cars are intrinsically better than used cars but that new cars cost such a premium compared to used cars as a signal of their quality. This also reflects the common human behavior of using price as a proxy for quality when we’re uncertain. Is there such a big difference between store-brand soap and name-brand soap? Probably not, but we’ll often happily spend many times the “generic brand” price for a name brand good as a form of insurance to ourselves that we’re buying a quality good. Yet, at the root of the economics of information is one key element: The cost and value of searching for more information.

Let’s give an example: You go to the fair and find you’re thirsty. Looking around at the nearby food stands, you see bottled water is for sale for an outrageous $10. Now, you could go search the fair for a stand selling water for a more reasonable price, but in most cases, you either simply accept that you’re going to be thirsty and don’t buy the water, or you pay the outrageous premium. Why? Because the cost in the finite time and energy you have to enjoy the fair compared to the cost of searching for better-priced water exceeds the value of paying less for water. Ultimately, people will engage in the search for a better price, product, or both, only so long as it is beneficial to do so. At the point that it stops being beneficial, they’ll either make a buying decision or a non-buying decision. A major factor that can influence how much time someone will spend on the information search is how great their opportunity cost is. For someone who is unemployed, all they have is time and, hypothetically, no money, so the cost of searching for them is considered very low. For a busy business owner, attorney, or even just a retiree who wants to get back to enjoying fishing, the cost of a search can be very high.

How this interacts with clients: Another example is poignant here. You’re a highly paid rocketsurgeon who makes $200 an hour performing rocketsurgery. You’ve read some blogs talking about how personal finance isn’t that hard, and if you can just commit the time to it, it’s much cheaper than using a financial planner, and that’s financially good for you. Yet, the demand for rocketsurgery is high and you’re very well paid to do it. So, do you spend five hours at an opportunity cost of $1,000 to manage your finances yourself? Are you certain that you can do it well for yourself without making any mistakes? How do you know? What if it takes much longer?

In fact, it will likely take much longer. A recent study found that CFP® Professional financial planners, who already know what they are doing with regard to personal finances, take an average of 36.5 hours to help a client in the first year of services alone. If we use the rocketsurgeon example, if the rocketsurgeon is somehow, if very unlikely, to spend only as much time as it would take a CFP® Professional to address their financial planning needs, they would spend $7,300 of their potential income on working on their own personal financial planning needs, if not significantly more in terms of time, and without the assurance and security of knowing that they were actually doing it right. Thus, if the cost of financial planning is less than $7,300 (at the most generous end of the assumptions), the rocketsurgeon rationally should hire a financial planner to take care of their finances rather than trying to do it themselves, and that’s just for the financial outcome, not even including the time and stress that goes into financial planning!

Human Capital Theory

Human Capital Theory is closely related to the behavioral life cycle hypothesis. It focuses on the investment of capital in order to increase earning potential, and is the dominant theory for looking at why people pay to go to college or spend time and money on other forms of qualification and education. The most simple premise is that people will invest money in increasing their “human capital” or the amount of income they can earn. They won’t spend money on things they don’t think will increase human capital, and their human capital expenditures will stop at the point at which they believe there will be no more return on investment (i.e., going for a 3rd master’s degree probably isn’t a great idea.) This theoretical framework has been used to examine the return on investments made in education, which have found significant returns on many forms of education and lesser returns on others.

How this interacts with clients: Many clients are dealing with their own student debt or helping their children pay for college. Often, the question of “how much to pay” and whether it’s worth it comes up as a point of discussion. Simply put, a financial planner’s role in the decision to save for education and pay for education comes down to the return on investment. While some degrees and schools may be appealing on their own merit, the financial planning question is often whether tuition is too high relative to the expected income it can produce or whether there’s a more optimal mix of cost for education and return on the expense. Ultimately, a key distinction of human capital theory is its emphasis on the return expected from the work the education is likely to produce. Thus, education for education’s own sake isn’t really an appreciated part of human capital theory, but it does suggest that if you’re into history, you should just read history books and not get a degree in it (speaking from experience, here.)

Comments 2

This article was surprisingly interesting to me. Surprisingly, because from the title I thought I would not bother to read it – but did start scanning and it turned out to be pleasantly informative. Thanks. P

Pingback: The Chicken or the Egg? Wealth or Financial Planner?