If you review any nationally representative dataset (the Survey of Consumer Finances, the National Financial Capability study, the National Longitudinal Survey, the Health and Retirement Study, among others), you will find an incredibly consistent data point: The higher the income, the assets, and the overall financial affluence of a household, the more common it is that they will have a financial planner. However, the problem with these studies is that they fail to address one key element: Which came first? The financial planner or the affluence? Without this causal relationship, the value of a financial planner might seem in question, but for their regular and popular presence among the resources the well-to-do rely on. But, this isn’t the only “chicken or the egg” problem in personal finance. So today, we’re talking about the chicken and egg problem in deciding whether to work with a financial planner.

Investment Return or Investor Return?

In statistics, there’s a term called “differences in differences,” which aims to address the different outcomes between two populations, one with a change in circumstances and one with another. The reason this term exists and the problem it describes is that there is a mutually exclusive reality: When you have a control group in a study and a treatment group in a study, what you cannot know is what would have happened to the control group if treated and the treatment group if untreated.

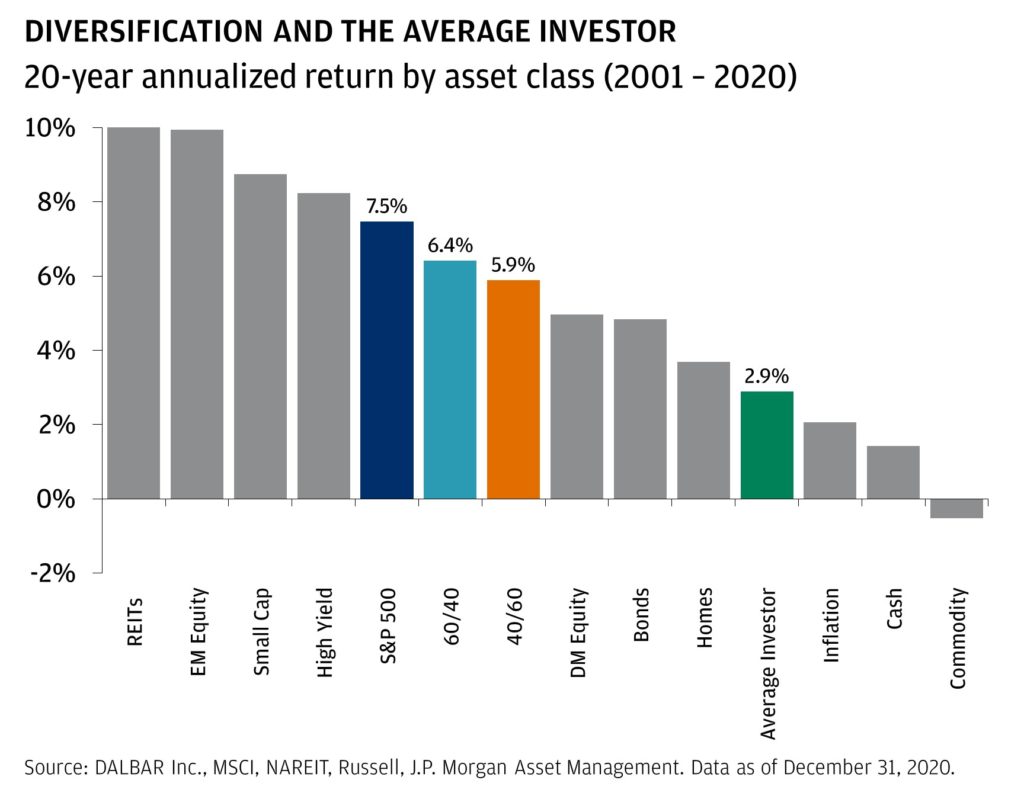

This problem pops up in the world of investing, particularly in the “fear of missing out,” in which we haven’t done something like put all our money into the hottest new thing, and we think “if only I’d done that, I’d be a bajillionaire now!” Of course, the inverse is true, that those who make hail mary investments that pan out well get to enjoy survivorship bias, feeling not only like they could see the future, but also naturally ignorant of the alternate reality in which they were wrong and are now destitute. We see the consequences of this dynamic in the market data. For example, JP Morgan has found that over the twenty-year period of 2000 to 2020, the average investor only gained 2.9% a year while other asset classes stretched as high as 10% annual average.

Source: JP Morgan

Yet, even over a hundred years of past market performance show that the longer we stay invested, the greater the likelihood of positive outcomes, with no twenty-year rolling period showing a negative average return.

Source: The Measure of a Plan

So what gives? Well, human nature, of course.

How do you perform as an investment manager?

This is a common question I get as a financial planner from new and potential clients. “How well do your investments do?” I always give a fairly straightforward answer: “We invest in passive index funds that track the market. So the simple answer is, we get the performance of the market minus the cost of having us manage your money. So if you manage your money the exact same way we do, you will end out better than having us do it for you because you wouldn’t have those costs attached. All you have to do is have the education, time, energy, and enthusiasm to do it yourself.” That sounds like four simple things, but those four simple things turn out to make a world of difference.

You see, if we look back to the JP Morgan chart above, this is the potential difference: Let’s say a client could have invested in an S&P500 Index fund, say Vanguard’s VOO ETF, from the start of 2000 to the end of 2020. The annual return over that time was 7.5% for the index, across the dot com bubble, 9/11, the great recession, Brexit, and even the start of COVID. The VOO return during that time, with a 0.03% expense ratio, was 7.46% (1.075/1.0003-1). If we were managing the exact same dollars, but charging our 0.50% fee on top of the 0.03% expense ratio, that same client would have netted 6.93% per year (1.075/1.0053-1). So if someone had invested $10,000 in the VOO fund themselves and stuck with it all twenty years, they would have ended out with $42,163.51, and if they’d delegated it to us, they’d have ended out with $38,193.67. That’s a $3,969.84 argument over twenty years in favor of just being DIY with your investments. Yet, I’m a financial planner who is paid by clients to manage tens of millions of dollars on their behalf, so why am I pointing this out to you? Because it relies on an incredibly specific and important set of assumptions:

- That the individual knew to pick that fund and had extreme confidence in its outcome.

- That the individual did not blink or bat an eye at the aforementioned market and world events that dominated headlines, sent countries into recessions, and even caused the collapse of some major financial institutions.

- That they would stick with it, without ever diverting or erring from their course.

Suddenly the assumption of education, time, energy, and enthusiasm might seem like bigger hurdles, and the evidence is clear that individuals truly lack the ability to satisfy those three assumptions consistently over time. Remember the 2.9% from JP Morgan above? That’s the reality for the average DIY investor. Applying the same math as the above example, that means that same investor only earning 2.9% instead of the desired 7.46% or our 6.93% would instead only have $17,713.63; in other words, despite the potential for a $42,163.51, the average investor would miss the mark by $24,449.88, which makes a pretty good $20,480.04 case for the case of hiring a financial planner at a cost to have attained $38,193.67 instead.

Differences in Differences of Time Spent

A theoretical model that draws well from the differences in differences problem is the economics of information. I wrote about this in-depth recently, so I won’t belabor it too much, but as a recap, one of the most important things someone can do is understand when their time is best spent on something or better spent on something else. In this case, the question is one of the value of time. One of the easiest explanations for why the ultra-affluent and high-income might hire a financial planner is a simple question of utility: They make more money doing rocket surgery or Instagram modeling than they would trying to track down pieces of the tax code to reduce their taxes by half a percent, and benefit even moreso by trading a fraction of that earning power to a financial planner so they can have the benefits of both, minus the cost, rather than one or the other. The simple leveraging of a financial planner’s time makes all the sense in the world when a range of studies have found that the value of a financial planner is anywhere from 1.59%–4.83% a year, when compared to fees that average around 1% of the going concern, yet, people still come back to that question: The chicken or the egg? Will the financial planner help me attain the financial outcomes that I’m looking for? Or once I have them will the financial planner just help me keep things together?

How do you feel about it?

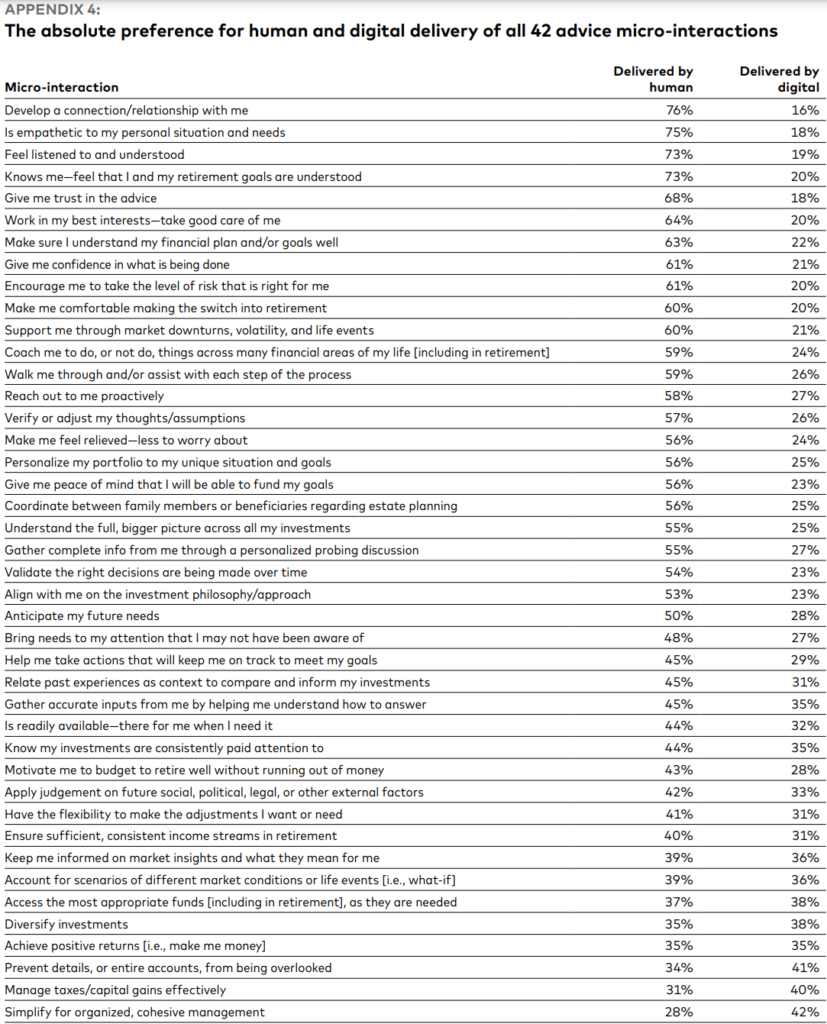

Well, rather than asking you, let’s ask a nationally representative sample. When Vanguard did a study in 2022, they found that not only did the public feel strongly that a human financial advisor was better than DIY or even using a robo advisor, but attributed to them unreal returns of a 5% improvement over what they could accomplish themselves. But even more importantly, the study sample indicated over and over that their confidence in sophisticated automated investing tools like robo advisors was substantially lower than their confidence in a human financial planner, along with having lower confidence in their own financial outcomes.

Source: Vanguard

The Wealth or the Financial Planner?

Ultimately, which comes first really doesn’t matter too much, except in how you think about accomplishing your financial goals. You may be confident in your own path and abilities and not need the help of a professional; plenty of people make that choice, but they will live with the uncertainty of “what if?” Alternatively, many others choose to take the help of a financial planner, and while the outcomes they might attain on their own become unknown in that situation, they do gain much greater clarity about their path ahead. So, regardless of the path you ultimately decide to take, just keep in mind: the data is clear on one thing. The financially successful overwhelmingly use financial planners. It’s on you to decide if and when you want to take advantage of what they have to offer.