I am a fairly demanding person in my professional relationships. I expect my attorneys to be sharp, accountants to be fastidious, and so on. However, this puts me in a position to be often disappointed, and to be fair, what can I expect? The tier-one customer service agent at a big tech company can’t really be expected to be “the best of the best” at their job when they’re likely paid $12 an hour in a call center. Yet, a colleague of mine likes to regularly remind me: “Just about everyone is bad at their job,” and when you frame your interactions with many businesses and “professionals” with this in mind, suddenly the challenges and incompetence you regularly interact with make a great deal more sense.

You might ask yourself: Okay, why are we reading about Dan’s disappointment with the service he receives? Well, because this week, I’m going to write about something I don’t care about, want to write about, or even think matters at all. Yet, it demands attention from the public at this particular moment, and thus as my clients and readers, I owe you an explanation of something that can be easily explained by the phrase “everyone is bad at their job.” I am, of course, writing about the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (“SVB”), which has dominated the news for the past few days. I’m not going to shed light on anything revelatory or new that better informed and more passionately involved journalists haven’t already reported on; after all, I’m not a journalist, and it bares repeating: I don’t actually care about SVB’s failure. However, in its rush to report on what happened to SVB, much of the writing has been in “finance speak,” which makes it much harder to follow and understand unless you work in finance. So today, begrudgingly, I’m translating what happened to SVB, why it’s the result of people being bad at their jobs, and why it probably doesn’t matter to you.

The Business Model of a Bank

Before explaining how SVB failed, you have to understand the business model of a bank. Simply put, a bank takes in depositors’ dollars, which are “excess money” to those depositors since they don’t need the money to spend at this very moment. This creates a liability or debt on their balance sheet since they owe the money back to you. They then offer loans to people who need money immediately. The business arrangement then is that they charge the borrowers of money from the bank more than they pay the depositors of money at the bank in interest. Ideally, most or all of the loans the bank makes will be collateralized by a house (mortgages) or a car (auto loans), and in cases where it can’t be (credit cards), credit ratings play a bigger role and interest rates are much higher because of the decent risk that the borrower might fail to pay back the loan. Banks then often compete, at least in part, on narrowing the margin between what they’ll pay depositors and what they’ll charge borrowers. For depositors, the higher the interest rate paid on savings, money market accounts, and CDs, the more interest the bank needs to generate from its loans. In turn, the less a bank charges on loans it offers, the less interest it can pay. For the bank to function, there has to be some margin between interest paid and interest charged but to be competitive, these often can become a somewhat narrow range.

Of course, the bigger issue that can occur is when a bank has too much money deposited and not enough loans to generate interest. To solve this problem, since the repeal of the Glass Steagall Act in 1999, banks have been able not just to loan money out but invest money to generate interest for their depositors. This became the case with SVB, which offered good enough rates to its customers that it saw a large multi-billion dollar deposit influx over the past few years, which it then could not efficiently turn into loans to generate interest, and as a result, ended up going to the investment market to buy investments to help it generate the interest it was promising its depositors. This introduces the key risk that saw the collapse of SVB.

Investment Duration and Interest Rate Risk

Let’s simplify a complex topic. If I ask to borrow money from you for a day, how much interest would you charge me? Now, think of that interest rate for a moment and then let’s ask a slightly different question. What if I want to borrow money for a week? What about a month? A year? Five years? Ten years? Thirty years? If you logically follow this sequence, it makes sense to you that the longer I’m going to borrow your money for, the more interest you should charge me, because there is a greater and greater risk to you that I might not pay you back. The risk that I might not pay you back is present every single day, but there’s much greater risk in not getting your money back if a loan is for twenty-four years than it is for twenty-four hours. This is a key principle for the bond and fixed-income investment market. Because this marketplace is made up of what are, in their essence loans, the length of a loan plays an important role in the interest rate that is charged. However, interest rates change over time. The “risk-free rate,” that rate offered on loans to the federal government in the form of US Treasury Bills, is considered the “floor” for current interest rates. It makes no sense for anyone to give a loan paying you back interest at a rate anything less than the T-Bill rate at any given time, because there is greater risk in lending to any private party or business than lending to the federal government (politics-obsessed nerds can debate this point, but that’s a separate topic.) Thus, the entire lending market reflects a desire for a “risk premium,” or a reward for taking on greater risk than a risk-free investment, in interest rates higher than the current rate offered by the federal government on treasury bills.

Now let’s think about the example of you lending me money again. If the current risk free rate is one percent, you should charge me an amount greater than one percent. That amount should reflect your perception of my creditworthiness, or the likelihood that I’ll pay you back, and the length of the loan. With that assumption in mind, we then have to ask a question: What if the risk-free rate changes? Now, if you hold the loan until its term (a day, month, year, thirty years, however long), then this doesn’t really matter to you. But let’s say you’re lending me the money for ten years, and five years down the road you decide you need your money back. What is your option? I have no obligation to pay you back faster, that wouldn’t be fair to me as a borrower, and no borrower would reasonably agree to that condition. So your only option is to sell my debt to you to someone else. Ideally, you can get the money you borrowed back. But now think about that risk-free rate. In essence, the person buying my debt from you is making a loan to me. In their eyes, the value of buying the debt from you is going to reflect the risk premium of lending to me instead of the government, and in turn, that means that the risk-free rate has to come into account. If it’s still 1%, they should buy it from you for about what the loan has always been worth up to this point. If the risk-free rate has gone up, however, that means the margin between the interest I’m paying you and the risk-free rate has gotten smaller, meaning that the risk premium is less valuable. Thus, you’re likely to take a bit of a haircut on the price, because otherwise they wouldn’t buy it from you. The inverse is also true: if the risk-free rate has gone down, the premium has become more valuable, and you can probably sell the debt for the original value plus an extra amount for the added value. This became critical in the collapse of SVB.

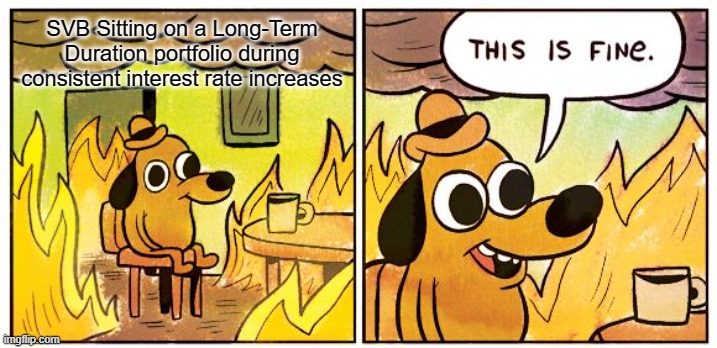

What Set SVB Up for Failure

As mentioned earlier, SVB was offering great interest rates to depositors, and as a result, it saw a big influx of cash over the last several years. It attempted to turn all of the cash into loans, but it turns out it’s harder to lend billions of dollars than you might think. As a result, SVB sought to invest money in long-term treasury bonds, those that have a minimum lending period of ten years or more. However, this meant that their investments in treasury bonds became riskier and riskier as the Federal Reserve began to raise the floor of the risk free interest rate from essentially 0% upward now to just shy of 5% over the past year. Now, this wasn’t necessarily a problem on its face. So long as SVB could hold onto the treasury bonds for the ten-year duration, they’d pick up the interest payments from the bonds, use those to pay depositors their promised interest, and all would be well. But last week, several individuals with large social media followings, along with those involved in the venture capital ecosystem began to tell their customers, clients, colleagues, and followers to get their money out of SVB. Within one day, depositors attempted to withdraw about $42 billion dollars from SVB. This was the tipping of the first domino. While the first couple billion dollars were likely held in cash at SVB, as soon as the bank ran out of cash, it was forced to start selling its investment holdings. The treasury bonds they had held for the past year or two had lost a significant amount of their value over the last year, not in terms of interest payments, but in their ability to be sold for their original value, because their interest rate payment from issue a year or two ago with a ten year minimum holding period was now just about equal to today’s risk-free rate. In essence, anyone buying the bonds from them wouldn’t want to pay more than a nominal amount, because they could get an investment return just as good with a much shorter lockup period in the form of newly issued treasury bills.

What Incompetence and Complacency Are and What They Aren’t

You might recall that in January of last year, we announced we were going to make a significant change to our investment portfolios. It might be memorable because we make a point of being good at picking long-term investments in the first place that don’t generally require us to make changes that often. However, the risk we cited at the time was the risk we’ve been talking about: That the Federal Reserve would begin raising interest rates, and as a result, the long-term bond holdings we’d had in place since 2019 would lose a lot of value in the near future if we kept holding onto them. As a result, we shifted all of our bond holdings for clients to short-term and ultra-short-term durations, essentially 2 years and less, which allowed them to pick up interest payments (better than cash under a mattress would) without losing much value in the secondary market as a result of the increase in interest rates. This is the risk that incompetence and complacency, perhaps, played a role in for SVB. While we made a deliberate point of reducing the duration of our bond holdings to avoid a hit in the event we had to sell bonds in the secondary market, SVB had made promises to its depositors of certain interest rates, and as the Federal Reserve kept raising its rates, so too SVB had to do so, as with every other bank, to remain competitive in acquiring new clients and deposits. The result was not an immediate problem: Again, if they could hold into the treasury bonds, then it wasn’t a problem because those bonds would pay interest that the bank could use to make interest payments to depositors. But, when your depositors want $42 billion dollars back on a random Thursday, suddenly, the loss of value in the ability to sell treasury bonds in the secondary market becomes the biggest problem in the world, and it ultimately crashed the bank.

The header of this subsection calls into question “what incompetence and complacency are and what they aren’t.” Was it incompetent of the bank to buy treasury bonds in such volume when it was likely that the Federal Reserve would raise rates in the future? Probably. But more importantly, it was complacent to think that they couldn’t possibly have such demand for withdrawals that they could be forced to sell the treasury bonds at such a steep discount that they’d fail as bank? Almost certainly. Now admittedly, it might be “unthinkable” that depositors might want double-digit percentages of your entire balance sheet back overnight, but that was where the history of bank runs and the Federal Reserve came into existence in the first place just 110 years ago: to create a backstop in the event that a bank’s depositors wanted more than the bank could afford to give back at any one time.

Why It Probably Doesn’t Matter To You

Simple question: Do you have more than $250,000 in a single bank? If so, then it might matter to you. If not, then you are well protected by FDIC (or NCUA) insurance. FDIC stepped in over the weekend to take receivership (essentially taking over the bank) and to ensure depositor funds could be made accessible as needed. This means the bank is essentially done for, and there will likely be both civil and criminal investigations regarding the incompetence of the executives and board of directors for SVB. But in the meantime, as far as you’re concerned, if you have less than $250,000 sitting in your checking or savings at the same bank, your money is safe. What if you have more than that? Well, we should probably have a conversation about investing some of it, but sans that small advertisement, you can mitigate much of this by simply spreading your money out across multiple institutions. This might mean manually moving your money between a few bank accounts, or otherwise using cash management tools like MaxMyInterest or Flourish* to spread your funds out between several banks automatically, not only for potential interest rates but also to expand your level of FDIC insurance.

There have been some articles since SVB’s failure last week pointing out similar vulnerabilities on the balance sheets of several large and small banks around the country. However, the key element described in the collapse of SVB isn’t that they had too much unmarketable long-term debt (more than they should have, anyway), but that the long-term debt on the balance sheet only became an issue when their depositors suddenly panicked and attempted to withdraw about 1/5th of the bank’s funds all at once. So long as you and your fellow depositors at any bank don’t rush to the exits all at once, these banks should be alright, even with a slightly risker-than-advisable balance sheet. We will no doubt see many banks start shifting their portfolios to account for these risks over the coming months, and we will probably see some laws passed and some revisions to the FDIC insurance limits that follow, given that they haven’t moved in decades. But in the meantime, so long as your funds are held safely under FDIC insurance limits at your bank, NCUA insurance limits at your credit union, or SIPC insurance limits at your brokerage, you will be fine. Thus, as I said at the outset: I didn’t care about SVB’s failure, want to write about it, or think it matters at all to me or to you. But, now with a better understanding of what happened, I hope you’ll agree with me.

*We reference MaxMyInterest and Flourish as examples. We are not affiliated with either of these firms, nor do we make any representations of their services other than the brief summary provided for education purposes.

Comments 2

I, for one, was interested in the explanation of why those banks failed. And I appreciate the attempt to ease the rhetoric into simpler terms. Thanks, P

Thank you, Daniel! K