A colleague of mine, a CPA by the name of Michael Pharris, has a framed piece of paper in his office. The header reads, “Hearn’s Laws”, written by Professor Hearn, an instructor when Michael was in undergrad studying accounting. While there are many good tidbits on the paper (“he who signs the other man’s form, takes care of the other man”), I’ve often condensed it down to its most valuable insight and simply called that insight Hearn’s Law: “You will pay for what you get, and if you’re lucky, you’ll get what you pay for.” I raise this bit of printed wisdom to your attention because today we’re talking about cost and value. A popular expression among salespeople is that “Price is only an issue in the absence of value.” It’s a nice idea, with a few obvious loopholes in it, but the idea is there. We’d all balk at paying $20,000 for an onion, but we’d all find our wallets if someone was trying to sell a brand new Mclaren F1 for the same price (if only to then sell it for its actual value and pocket a cool few million dollars, after a test drive of course!)

However, these ideas become murky in the presence of ambiguity and what academics call “credence claims,” which are claims made by professionals that cannot guarantee an outcome. For example, a mechanic tells you they can fix that weird noise your car is making. You pay them, they work on the car, you pick it up and there’s no more weird noise, but a few days later another noise starts. Did the mechanics actually fix anything? Hard to say. With the ideas of Hearn’s Law, price and value, and credence claims in mind today, we wanted to spend some time explaining our journey through the pricing of financial planning services, the services we offer, and how they compare in a world of financial advisors, consultants, and wealth managers.

Getting to Today

When I first started as a financial planner, it would be fair to say that I didn’t really know what the value of a financial plan was. I understood that it took work to meet with a potential client, learn their needs, spend a dozen hours developing a financial plan model, and then presenting that model to them before moving onto helping them implement their financial plan, but I couldn’t have told you up front what a “fair price was.” In fact, my first several financial plans were no more than $500, with more than a fair few costing only $300. These plans would take easily fifteen to twenty hours to develop, along with what may have been a long sales cycle to get to the point of even being hired. Further, I wasn’t taking home the full $300 or $500, but was keeping about 60% of it while the other 40% went to Waddell & Reed, the firm I’d affiliated with when I started my practice. In other words, some of these twenty-hour $300 plans were paying me about $9 an hour before taxes. Not particularly great money for someone with an MBA! There was, of course, the follow-on benefit of doing financial planning so affordably, which was a great deal more “at bats” for potential clients and the opportunity to then highlight the value of services like investment management or the occasional opportunity to help put a disability or term life insurance policy in place. Ultimately, the sales of those additional services beyond financial planning were the things that kept the ship afloat in the early days, but it always felt strange that you could be paid as much if not more to simply help a client apply for a term life policy as you could be for spending dozens of hours on a financial plan model.

Even as the next few years went on and my confidence in the value of what I could provide as a financial planner increased, I found myself a bit skeptical of the prices people said clients might pay for financial planning. The internal director at Waddell & Reed for financial planning, essentially an internal consultant, calmly explained that the minimum we should charge for a financial plan was about $1,300 a year. A year later (2016) he was showing us research that the average millennial would pay about $150 a month for financial planning advice, or $1,800 a year. It just didn’t seem feasible! Yet, to my surprise and delight, it seemed that it was my own lack of confidence that had discounted the value of financial planning, not the public’s perception. People didn’t bat an eye as I gained the confidence to ask for over a thousand dollars, then over two thousand dollars, and so on for financial planning. They believed in the value, even as I was slowly building confidence in the value of financial planning. Inadvertently, I’d psychologically anchored myself to the point that “financial planning is only worth $300-$500,” when in fact, it was the most valuable thing I did for clients.

Over the next few years, I tested and developed several models for financial planning services. The first model that was nuanced beyond flat fees was one that was based on complexity, specifically overall client asset levels, forms of income, number of accounts, and types of already existing investments. It worked fairly well, but it occasionally struggled to account for the real complexity of a client’s situation. After all, a ruler is only so good a tool of measurement for distances but can be a poor measure of weight and temperature. So too I found were the issues in having specific metrics for financial plan development; simply put, it was too complex to capture in just a handful of variables. The next model I used was one that simplified the number of variables for consideration in setting the fee, but also introduced both net worth as another metric for fees and also broke up the planning engagement into an initial engagement and an optional ongoing subscription service afterward. However, this model too had issues, in which we would often see people decline the subscription after the initial plan service, only to ask to come back for more advice a few weeks or months after the initial engagement was done, then balking at the ask that they sign onto the subscription to do so. Simply put, by framing financial planning as being about “the development of the plan” and the process of financial planning as being “something else,” we’d inadvertently biased some of our clients into thinking that the value was in “THE PLAN™” and not in the act of planning and adjusting the plan over time to changing circumstances.

Then in 2020, I began a Ph.D. in Financial Planning, with a particular interest in compensation research and a focus on how financial planners charge and how they’re paid. While what I’ve researched is the subject of an entirely different paper, some insights have been helpful in developing the fee model we use today.

Our Fee Model Today

Simply put, our fee model today is 0.5% of net worth annually, divided into monthly payments, with an annual minimum of $3,000. For those rare cases where there is only an investment management issue (management of trust assets, for example), we charge an industry benchmarked 1%, but as you’ll see in a moment, even that benchmark is lower than you might expect. The simple rationales behind the service model are as follows:

- Charging an up-front lump sum fee ensures we’re fairly paid, but can be financially burdensome to those with a tight cash flow. Spreading the payments out over a year ensures that engaging our services isn’t determined solely on the balance of a savings account.

- The most recent study by Kitces on “How Financial Planners Actually Do Financial Planning” shows that the average first-year financial planning engagement takes 36.5 hours. For reference, my associate planner’s compensation comes out (net of wages, taxes, benefits, 401(k) matching, etc.) to $51.24 an hour, not even including the cost of the tools, technology, and other overhead we use. Succinctly then, if she, and only she works on a client engagement in the first year, our minimum cost of delivering services would be expected to be $1,870.28. However, we work as a team, with my associate planner often doing some of the more basic and developmental plan work on her own, with me then reviewing and working with her to finalize the plan model, and each of us attending most if not all client meetings together to ensure accuracy. When my own time is taken into account, costing approximately $107.77 an hour (again, without overhead or other factors included), were I to complete every step of the initial plan and first year planning services by myself, I would actually be losing money, since the cost of delivering financial planning services in the first year would be $3,933.60. Simply put then, $3,000 serves as a healthy medium for many clients with a “basic” financial planning need, let alone those who have more developed and advanced planning needs.

- Our focus on net worth makes us an oddity in the financial planning landscape, but for a very good reason. The vast majority of fee-based and fee-only financial planning firms charge a fee based on “assets under management” (“AUM”), typically as a percentage. However, this service model means that those planners cannot serve clients without a high net worth (the same Kitces study as earlier suggests that AUM-focused planners only serve the 89th and above percentile of income with more than $1m in assets) and also creates a clear conflict of interest. Any time a client wants to make a distribution or asks a question about paying cash versus financing, the financial planner is immediately incentivized to suggest financing or paying over time rather than paying with lump sums. While this might be the right advice in the right case, it’s still an unavoidable conflict of interest. In turn, we also declined to provide an hourly model; simply put, if we charge fair hourly rates for our service model (average pricing is around $250, with many hourly-specialized planners charging upward of $400 an hour), our prices would be easily doubled or tripled for most clients, which would in turn create a conflict for both us and our clients: Should we cut back on scope of work to keep it affordable and would our clients be hesitant to call us when needed because of the expense? Hourly is great for firms with a limited scope of engagement service model, but for a firm like hours that focuses on comprehensive planning, it would be prohibitively expensive.

- We ultimately decided to bundle financial planning and investment management services. A lot of pundits in financial planning land advise separating financial planning and investment management services and their pricing because they are fundamentally different services with different fees; yet, we have found over the years that cost-conscious clients would often forgo investment management for a DIY approach, only to make costly errors and mistakes that far outweighed the cost of management. In turn, those handful of clients who only wanted investment management never seemed to quite shake the habit of having “just a few questions” around taxes and other financial topics. Thus, simply bundling everything into one service model assists us in simply ensuring that nothing is out of scope for our clients. This also helps us serve clients that are often neglected by other service models, such as those with an interest in entrepreneurship or real estate ownership, where a model traditionally focused on management of stock portfolios might say “sorry, you’ll have to invest through us or we can’t help you.”

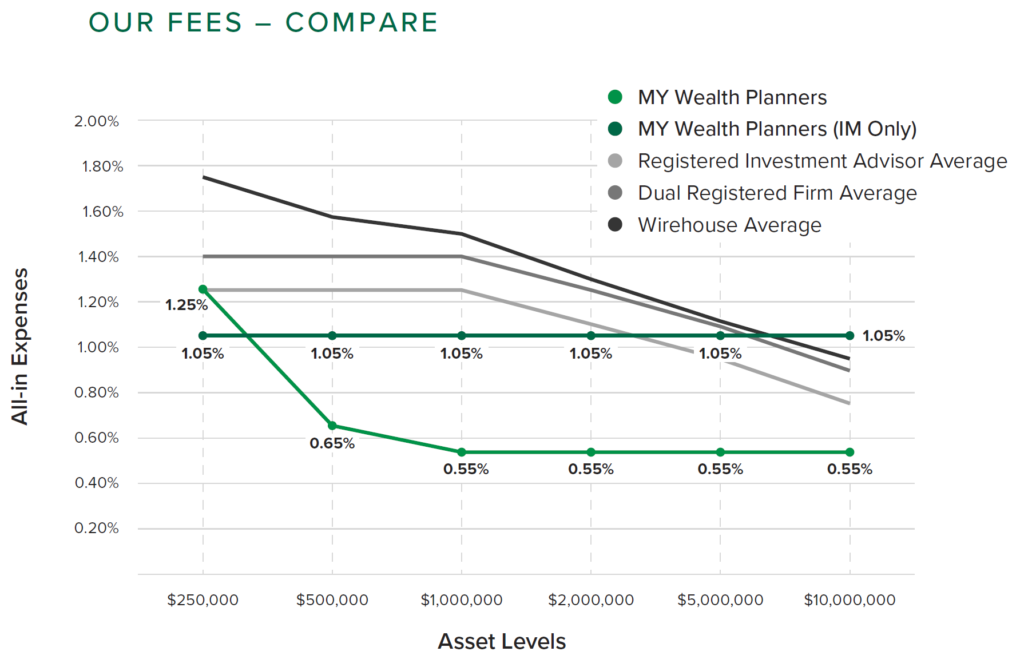

With these items in mind, how do our fees shake out? Well, in comparison to industry benchmarks, it turns out that the answer is “extremely competitive,” if not outright underpriced.

For a client at the start of life with about $250,000 of assets (assuming no liabilities), our fees would come in around 1.25%, which benchmarks exactly onto the same net costs as a registered investment adviser firm only offering investment management services. One can then see that our financial planning fee quickly declines down to a level far below other service model’s fees, and never pokes its head above. Now, for the rare cases where a client asks for investment management only (again, something like a family trust), one can see that our investment management-only fee stays well below the costs of other service models well above several million dollars.

Now, a critical observer will highlight a few obvious issues, perhaps even “chart crime” here, so let’s talk about those issues. First, we’ve said that our fees are 0.5% for financial planning and 1.0% for investment management, yet we’re showing 1.25%, then 0.65%, then 0.55% for financial planning and 1.05% for investment management. What’s happening here? In the case of investment management, we’ve included not only our service fee, but the average cost of the investment products we’d recommend for clients, as all of our investment portfolios average 0.04%-0.06% in product costs for low-cost ETFs; we’ve included this as well in our calculation of financial planning fees, but the ramp down from 1.25% to 0.55% simply reflects the fee minimum we mentioned of $3,000. If your net worth is lower, as a percentage, that fee can be much higher. Thus, our fee model may not make sense for individuals with extremely low net worths without a substantial income to offset the cost, or otherwise those for whom $250 a month might be more than is affordable. The next criticism someone might levy is that we’re comparing our fees based on Net Worth to fees based solely on assets under management. That’s a fair critique, but one that’s hard to mitigate. As AUM fees don’t reflect issues such as mortgages, student loans, and other liabilities, they might simply “overcharge” relative to net worth, but charge fairly as a ratio of the investments under management. In turn, charging on Net Worth for clients without any liabilities or debt might mean charging more than a comparable AUM-based firm if the client’s investable asset balance is low but their tangible assets such as rental properties or their primary residence are significant.

Hearn’s Law – We’ve Talked About Price, But What About Value?

Well, having been fairly long-winded in an explanation of the cost of services and why we charge what we do, let’s now consider what’s being paid for. Simply put, there is no such thing as an objectively measured “financial planning service.” This might seem odd since I’ve talked so much about it, but it’s a real issue. In the first class of my Ph.D. program, I excitedly shared with my peers and the faculty about my idea of doing a study in which we would measure the efficacy of financial planning by improvements to net worth, with the idea being that we could compare service models and costs to the changes in net worth and determine whether a service model was “good, bad, better, or worse” in its effect on net worth. This idea was quickly poked full of holes by one simple issue: Financial planning differs wildly from planning firm to planning firm, but also, so to do client goals! Not everyone on earth is looking to grow their wealth over time, and in fact, many are looking to use it or give it away. Measuring the success of financial planning is simply difficult, if not impossible to do, in any sort of way that can be uniformly measured across various households. So, what can we do to provide value?

Simply put, our unique take on financial planning is to take the burden of thinking about money in more than a convenient way off of our client’s plates. We want our clients to know they have money, “enough money,” or that they are on the path to having the money they need to live their best lives. We don’t want them to sweat questions of whether things could be in the future, or whether they will get to live the life they want, or whether they can afford something when an event or occurrence arises. We want their first thought to be: “Let me just shoot MY Wealth Planners that question” and to know that it’ll be answered for them. That’s the ideal delivery of financial planning in our mind. Hopefully, our clients agree. Not only that they pay for what they get, but that they get what they pay for.

Comments 1

Your last paragraph says it all – that is why I have hired you. (smile)