As the old expression goes: “You can’t have your cake and eat it too.” Yet it seems there are cultures both among aspiring financial planners and financial planning firm owners that attempt just that. Students and career changers have casually shared with me time and time again that they’re looking for a position for two or three years that will get them the skills and knowledge they need while paying them well, then plan to spin off and start their own firm. Simultaneously, firm owners bemoan the lack of talent in the financial planning field while offering terrible pay and benefits and treating everyone who applies as if they’re lucky for the opportunity.

The question arises: How can these cultures coexist? Simple answer: They don’t. The plight of the students and career changers is a lack of opportunities, and the plight of the firm owners is a lack of people willing to take what they have to offer. So today, we’re talking about the “pick two” problem faced by both students and career changers and what needs to change to bring these points of view into greater alignment.

Why

As Sinek said: Start with “why.” The reason this is important to anyone who might read it is simple: Financial planning is growing in the wrong direction. That’s not a comment on the industry zeitgeist, financial products, or compensation models. It’s a statement of demographic change. The average financial planner is in their late 50s and is expected to retire within the next decade. The CFP Board “mints” approximately 7,500-9000 new CFP® Professionals per year. If we take Cerulli Associate’s estimate of 330,000 active financial advisors in the United States and play those numbers out, that means we’re expecting to net negative, at best, 75,000 financial advice professionals over the next decade unless there is a serious trajectory change in its growth and attrition rates. If these problems aren’t addressed, this will mean greater competition for financial planning talent, higher costs for consumers, and ultimately the slowing or even shrinking of access to financial planning professionals. Financial planning has always struggled to be seen as something other than simply a luxury service for the ultra-wealthy. If the issues of recruiting, hiring, and retaining talent within the industry aren’t addressed, then it will actually become a luxury service only for the ultra-wealthy.

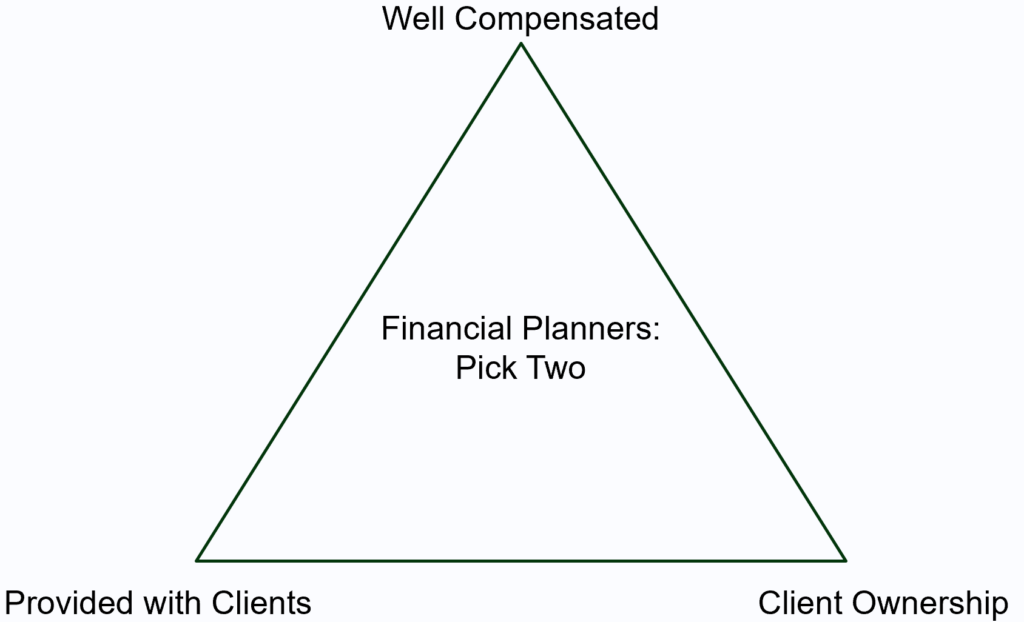

Financial Planners Pick Two

For the aforementioned students and career changers, the idyllic path is often that they’ll get a good salaried job that has them working with clients early on. The firm will perform all the marketing and business development, give the planner dozens of client relationships, and when the planner feels ready, they’ll leave the firm and take the clients with them. It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to see the obvious conflicts at work here, and so they have to be recognized and accounted for.

For a financial planner to be well compensated and provided with clients, the firm has to have a sense of security that the firm is not simply subsidizing a junior planner’s future firm launch. In those instances, the firm typically applies a number of non-compete, non-solicit, or other mechanisms such as client confidentiality clauses to the employment agreements of the financial planner. With those in place, the firm can feel better about offering a decent salary and benefits and has the legal-esque comfort that they can give their staff new client relationships without worrying that they’ll walk out the door. Yet, even with these contracts in place, firms can suffer from the concern that their staff will attempt to get around the agreements or wait for them to lapse, ultimately still attempting to lure clients away when possible after they’ve left the firm. To some extent, this is an unsolvable problem, as there is no such thing as a life-long non-compete, and further, as the clear observation goes: Clients aren’t the property of the firm, they’re autonomous people who make the personal decisions about who they will and will not work with. The solution to this problem isn’t on the side of the financial planner, but on the firms themselves: Build a firm that has a clear value proposition for your employees so that they won’t want to leave, rather than attempting to ensure they can’t leave.

For a planner who is given clients without non-competes or non-solicits, it’s almost sure to be a case that the compensation isn’t great, or at least not for the workload it requires. This is typically in the form of a firm that does an extremely high volume of low-dollar work, such as retirement plan participant financial advice subscriptions or a call-center model. The lack of restrictions on client ownership isn’t because the firm isn’t aware that their staff could take clients with them, it’s that the economic value of any given client isn’t significant enough to fight over. Who is going to sue over a client household paying $8 a month through payroll deductions? While these jobs can be difficult because the work-to-pay ratio is brutal, these can be a really good opportunity for new financial planners to learn technical skills and practice the skill of giving advice to clients. Ultimately, the balancing act is how long they can stand the high workload for low pay, and how soon they feel ready to start something new.

Finally, we have what might sound like the best version of things: Client ownership and being well compensated. Of course, this is actually the most popular type of job track in the financial planning profession; why? Because fundamentally, it’s a sales job. Tens of thousands of these positions are filled every year because of the potential opportunities it represents. Yet, recent Cerulli data shows that 72% of rookie financial advice professionals fail out of the industry; this number is actually overly generous, as it includes those in non-sales roles. When narrowed down to the category of ownership and compensation we’re talking about, the survival rate shrinks to less than 15% over four years. So, while high compensation and client ownership seem like the holy grail, they have to be offset and considered in light of the fact that only about one in seven planners will actually still be in the profession less than a decade after they start.

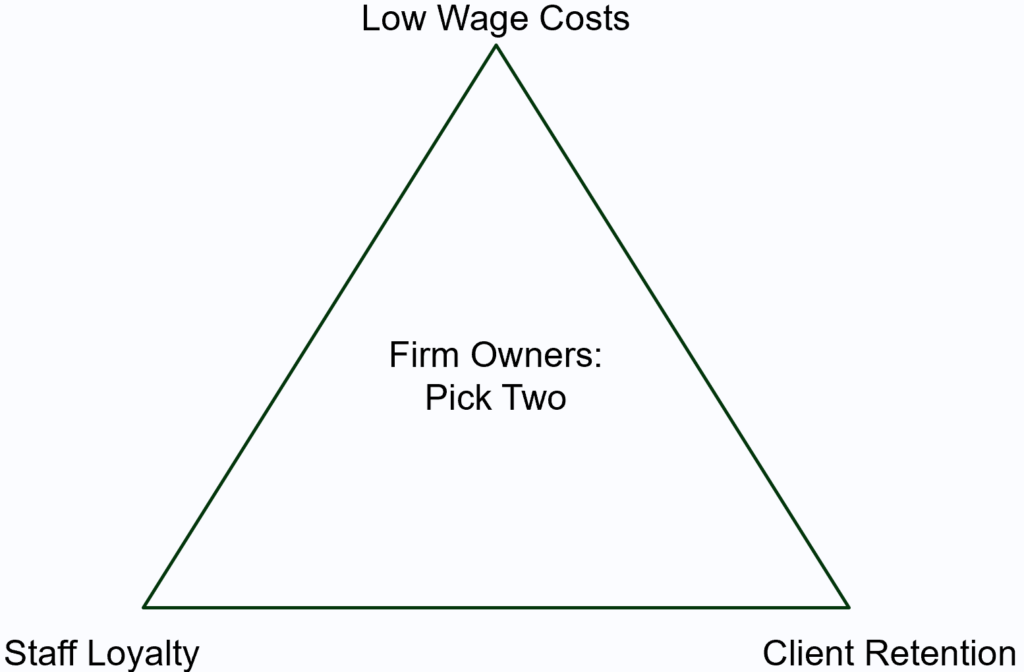

Firm Owners Pick Two

None of what we’ve had to say about the dynamics at play for the financial planners is said in isolation: ultimately, planners offer their labor, and firm owners set the terms. Yet, firms have their own staffing dynamic problems. While it’s easy to make claims such as “We’re such a great firm, we shouldn’t have these issues” or “People should want to work at the firm for reasons other than money,” the simple fact is that compensation and culture are just parts of the larger puzzle of hiring and staffing, and attempting to sit on a high horse indefinitely all but assures that you will be a team of one.

Many firms make a decision, perhaps unknowingly, that they’re going to have high client retention and low wage costs at the expense of staff loyalty. After all, retaining clients means there’s ongoing revenue to support and grow the firm, growing and operating a firm is expensive, so who wouldn’t cut a few corners? Yet, many firm owners are shocked when their staff leaves after only a few years or even months. “But we have such a great firm!” They exclaim to their spouse as they tell them why their junior planner resigned today, ignoring that they did so because the competitor up the road offered them $30,000 more per year. The simple and uncomfortable truth is that it is, in fact, easy to hire entry-level people in this field if you offer a salary and meager benefits. Salaried non-sales jobs are such a rarity by comparison to the sales positions that just about anyone will jump at almost any opportunity so long as they won’t starve to take it. But firm owners very easily get complacent in this regard and, within a few years, find that their staff is leaving them for greener pastures simply because they didn’t present a career path or compensation to match the growing skills and capabilities of their team members.

In cases where the firm has chosen client retention and staff loyalty, a similar paradigm presents itself as those that choose client retention and low wage costs. The differentiator is that they will have to pay significant compensation and benefits. Unlike other professions where money discussions are more taboo, financial planners are literally trained to think about money all the time. The result is that they have a strong sense of whether their compensation is fair or not, and given even the slightest feeling that they’re not being as well rewarded as they should be, may look for a better opportunity. The positive of paying competitively or even overpaying for staff, of course, is that you’re unlikely to lose team members over compensation and if the staff aren’t leaving, the clients aren’t likely to leave either.

Finally, the strange dynamic of choosing staff loyalty and low wage costs. The obvious issue here is that if you’re not paying your staff well but you’re still able to retain them, that client retention is likely an issue. The irony is that the retention issue likely isn’t driven by clients themselves but by the firm’s structure and culture. If clients are regularly coming and going because your firm operates on a call center or discounted model, it’s likely because they’re not receiving the full scope of services they’d hoped for when they engaged in a discount service provider (no surprise to us, but certainly to the client.) Thus, you can staff large firms such as Charles Schwab and Vanguard with thousands of loyal staff members who aren’t competitively compensated*, but that’s largely driven by a culture that says that clients are a dime a dozen and that the opportunity for a strong career in the company is still a possibility.

*It feels noteworthy to say that I’m not suggesting Charles Schwab or Vanguard employees are all grossly underpaid, but a salaried call center financial advisor position is never going to pay as much as a lead financial planner position with a strong independent RIA.

Bringing These Dynamics Into Balance

It starts with being honest, both on the part of the firm owner and the financial planner: What do you actually want out of this arrangement? Or, as Bo Burnham put it: Lower Your Expectations (a lot). It is not reasonable to expect firms to pay financial planners a premium to subsidize the launch of their future lifestyle practice. It is not reasonable to expect financial planners to work for slave wages and not look for other opportunities, either inside or outside of the financial planning profession. Ultimately, if firms and financial planners are being honest, there are countless good matches to be made out there, but it requires that everyone be clear about what they want. Financial planners shouldn’t apply to firms offering strong salaries and benefits if their ultimate goal is to leave the firm to start their own. Firms shouldn’t promise candidates an incredible career track or equity ownership and then constantly move the goalpost on what’s required to obtain it.

When a firm makes the decision to make its first hire, and every hire thereafter, the firm owner needs to be honest about how they intend to grow from that point and what that means for their team member. If the firm owner’s goal is to maintain a lifestyle practice with a little extra help, that’s fine, but they need to communicate that openly to every candidate and explain what that means. Does that mean they have the opportunity to one day buy the practice or become a partner, or does it mean that their purpose is to pass the butter for life? If an aspiring financial planner aims to one day be a firm owner, it’s incumbent upon them to honestly communicate this with firms that are hiring. That’s not to demand equity on day one, but to be honest about the ambition and ask whether there’s truly an opportunity for that ambition to be realized at the firm.

MY Wealth Planners’ Version

Because I know some will ask where we fall on this spectrum, my career as a financial planner started in the “client ownership/well compensated” category, launching a practice underneath the umbrella of Waddell & Reed. As the firm has gone fully independent and grown its headcount, I’ve made the decision to be a “staff loyalty/client retention” firm, meaning that we pay well over market rate compensation and benefits for every position. This in turn means the firm will grow profitability slower, but the turnabout has been a 5-year capital asset growth rate (CAGR) of 24.4% annually compared to a peer group median of 6.2% and a top decile peer group mean of 12.8%. In laymen’s terms, while the firm is not enormously profitable, it’s growing at 2x-4x the rate of its peers, and I credit that largely with building a culture that places the team and clients first and foremost above the profits of the company.

Dr. Daniel M. Yerger is the President of MY Wealth Planners®, a fee-only financial planning firm serving Longmont, CO’s accomplished professionals.

Comments 1

Pingback: Big Ticks: The Best Stories For Professional Financial Advisers This Week - Tony Vidler