If I tried to build a rocket ship, only one of two things would happen. At best, I’d go nowhere, and at worst, I’d explode. This seems fairly self-evident, given that I’m not a rocket scientist, and the highest grade I ever got in a physics class was a C+ in high school. The simple fact is that even though I was taught something about the subject, and even though I deal with physics every day as part of being a living person in reality, I really know quite little about physics, engineering, or chemistry. At least insofar as the endeavor of building a working rocket ship is concerned.

Yet, take that same obvious thinking, and apply it to finance. You utilize financial tools such as money, debit and credit cards, loans, interest, and investment returns in your day-to-day. You interact with money and finances all the time! Yet, unless you are one of my handful of banker or accountant clients, it’s likely that most of what you’ve formally learned about money came from your parents, who may or may not have been very good with money themselves or perhaps a home economics class in middle school or high school. By the same comparison to physics and rocket ships, then, you might wonder: “Am I, in fact, going nowhere? Or am I on a course to explode?”

While we’re not rocket ship experts, we are financial experts. So today, we’re talking about some of the most basic elements of money management: how couples can share and manage their finances, what is “equal” versus “equitable,” and other considerations as you build wealth by yourself or with your life partner.

Letting Default be the Decider

Often, married couples or long-term partners will mirror their cash management behaviors from when they were dating and bring those same behaviors into marriage. For couples who shared expenses or cohabitated before tying the knot, the approach is often to split costs in some varying degree of “evenly” and then to spend money separately. Those who got married quickly or in cases where there was only one income prior to marriage are more likely to simply share all income and spending from one large shared account. While neither method is intrinsically right or wrong, both can present problems.

In cases where couples split expenses but keep their money separate, there can be ignorance on the part of the right hand about what the left hand is up to. In the case of married couples, this might mean that one spouse is more heavily using credit cards than the other or that one spouse is saving a lot for retirement while the other is not. It becomes incumbent on couples in this situation not just to have visibility on each other’s bank accounts but, much more importantly, to discuss the overall finances of the household regularly. As financial planners, we facilitate these conversations regularly, but even those of you reading who are not working with a financial planner should make it a habit to sit down at least once per year to discuss who is earning what, saving what, and spending what, to make sure everyone is on the same page.

In cases where couples are simply sharing all costs, transparency can be helpful in this area, but it can also lead to conflict. When all income is shared into one spot, the fungibility of money can lead couples with uneven spending patterns to build up resentment. Who here hasn’t heard some grumbly old timer talking about how “she likes to spend my money”? Yet, despite this obvious gendering and the judgment it projects (whether it’s he or she isn’t actually relevant), it indicates a problem. Whether the money in the household is shared because only one spouse works or simply because it was agreed to early that you’d share income evenly, it’s clear that such a position leaves both parties in a position to get upset with the other about how much is coming in, how much is going out, and the perception of who is responsible for the spending and deciding what’s allowed and what isn’t.

Consequently, regardless of the system you’re using or have used in the past, it becomes incumbent upon you to make a conscious decision as a couple to create a cash management system that actually works for you.

A Cash Management System

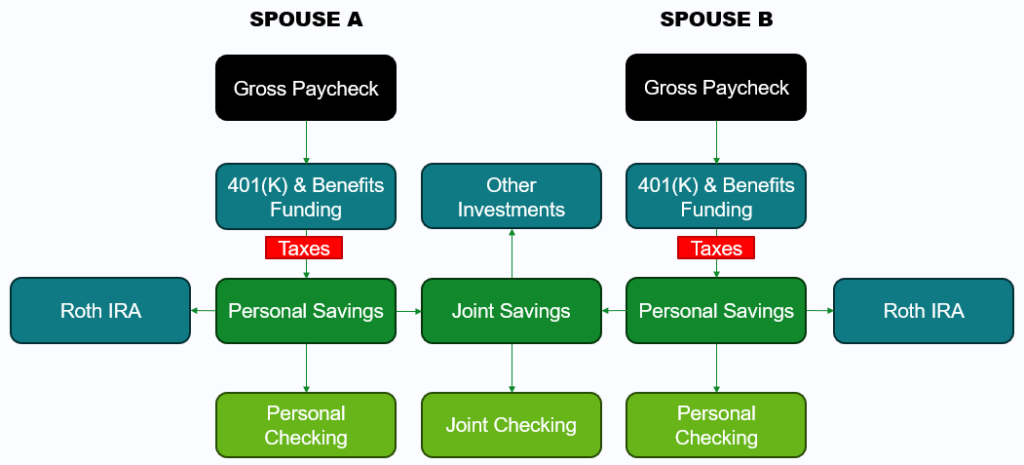

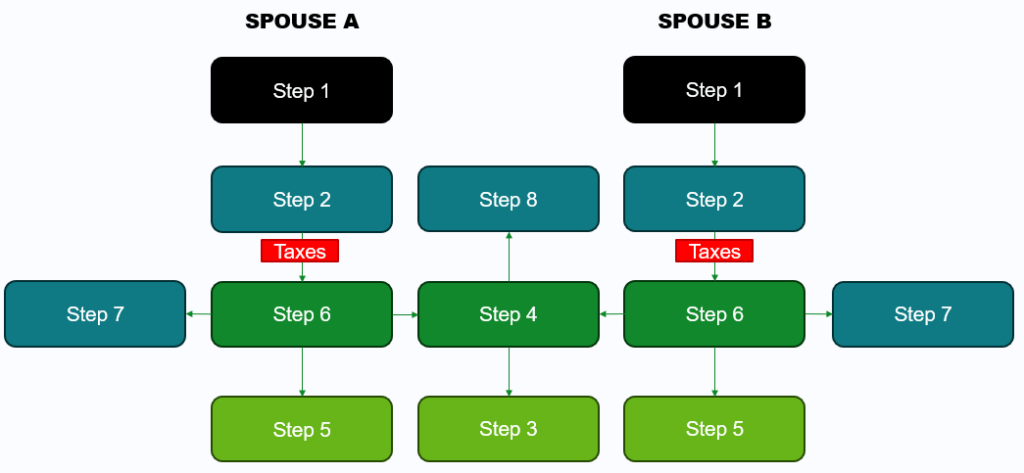

The diagram above pre-supposes a number of considerations and factors. First, both members of the household are working and bring in an income. Second, benefits such as retirement plan savings and insurance benefits are being deducted from paychecks, and both members of the household have their own savings. We’ll address some variations on this cash flow model towards the end of this section, but for now, let’s dig in, but instead reviewing this same flow but with an “order of operations” replacing the actual descriptions.

It doesn’t really flow through from top to bottom, does it? In fact, once we’ve gotten past the gross paycheck and the deductions for retirement and benefits, we’re skipping right past all the personal items and straight to the shared items such as joint checking and savings. How you divide up the “joint” accounts is the subject of our next section, but why emphasize this before any personal spending or other items? Because a household is one economic unit. Regardless of whether you or your spouse out-earns the other by 5% or 500%, you have shared expenses and a shared responsibility to each other. Consequently, all the mandatory expenses, such as the rent or mortgage, utilities, and groceries, need to be funded before all else.

Once you’ve gotten past the minimum monthly spending (e.g., “1 month of expenses”), which is the consistent baseline of the joint checking, you can focus on building up another two months of expenses in the joint savings. This provides your household with three months of expenses at all times to fund any changes in employment or income or to provide a buffer for shared expenses that might arise, such as a pleasant vacation or a less pleasant repair bill. Once both joint accounts are funded, you can then move onto “my” spending, aka the personal checking accounts for each of you. The funding mechanism for these, too, should follow a similar funding logic: one month of expenses as a baseline in checking, and two months of expenses in savings. Why double these up? Because while your shared household expenses are more uniformly measured, your individual incomes may differ dramatically, and as such, your regular consumption decisions may also vary dramatically. Though you share finances, one of you may have the income or lifestyle custom of stopping for a daily Starbucks, while the other religiously makes and packs a lunch for work every day. These consumption differences should be reflected in both your individual income and savings for such occasions.

Once both the joint checking and savings, and the personal checking and savings, are both topped off, there is a bit of a “stagger step” between step six and step seven. Before proceeding to step seven, you should pause to review the joint checking and savings. Are there any short-term financial savings goals that need extra funding? For example, do you plan to take a big trip, buy a new car, or perform renovations on your home? These should be placed in a high-yield savings account, money market, or CD as part of the “joint savings” tranche of the cash management model. While you might think to invest dollars for a goal that’s just a few years out, you want to be mindful that while long-term investment returns are historically very stable over time, periods of just a few years can be volatile. So if your potential expense is time sensitive and time is short, keep the risk low.

Once that’s addressed, your next step is to fund Roth IRAs (details on whether you can do this directly or need to perform back door contributions are found here.) This step is quickly followed by step eight: other investments. This step can be mixed up with maxing out your retirement savings through work or using any other tax-advantaged options available to you. Ultimately, this is about building wealth using tax-advantaged vehicles over the long term, so while Roth IRAs are the default, other options are on the table. If you’ve maxed out all available retirement savings options, then you can finally look into options such as a taxable brokerage account or real estate investing, though you should be cautious about not getting too far out over your skis with regard to the investments you do that are beyond the norm of highly diversified low-cost investment products (i.e., mutual funds, ETFs, etc.)

Equal or Equitable Cash Management?

Another common issue that arises among couples is this: how do you split the check? There are plenty of arguments for splitting things evenly. After all, you might live in the same home, eat the same food, use the same electricity and water, and so on. Yet, the more disparate your incomes, the more likely this will cause problems. Splitting a $4,000 mortgage evenly might seem fair on its face, but it makes a lot less sense when one of you earns six figures and the other earns less than forty thousand per year. This can also create some friction in cases of even one-time expenses, such as a family vacation. So, ultimately in this area, we favor equitable over equal: Divide expenses based on what’s fair, not what’s equal. Fair, here, should fundamentally reflect your post-tax income, but not your post-benefits or post-retirement savings income. That should be a key conversation between partners. “If I’m paying for all of our health insurance, that’s a contribution to the equitable division of our expenses.” “If I’m maxing out my 401(k), that’s for both of us, not just me because my name is on the account.”

Remember that from a legal standpoint, marital income and assets are just that: marital. An equitable division should take into account that one of you may have a much higher level of tax withholding because of your income level, but that in turn, you still likely end up with much more net-of-tax income. Simultaneously, you should keep in mind that your income as a household is fungible. For example, among couples where one spouse works for a PERA-participating employer, we will recommend that the spouse working for the PERA-participating employer contribute not only to the pension, not only to the 401(k), but also to the 457 plan. All in, this means a teacher earning $60,000 a year might be contributing as much as $50,800 to the household’s retirement each year! That’s an enormous contribution to the wealth of the family, and one that can’t fairly be addressed by then saying that you still have to split the mortgage payment equally!

What about couples with one income?

The ideas in the diagrams above don’t simply change because of a change in income. It’s still important to recognize that even if one spouse is a stay-at-home parent or doesn’t otherwise work, that they do contribute to the overall activity and success of the family. Thus, while it might be tempting to put that spouse on an “allowance,” a more appropriate approach is to consider them an equal earner. Consequently, this means that while the joint checking and savings still need to be funded, that both spouses should still be entitled to their own unique checking and savings, and by extension, as the household wealth grows, to contribute to Roth IRAs or other savings and investment vehicles as well.

What about college, FSAs, or HSAs?

Some readers will rightly note that I’ve left out college savings plans like 529s or HSAs. Simply put, prioritize these at the point that you reach step two (HSA/FSA) and step seven (529). HSA and FSA accounts are both powerful healthcare and childcare expense savings tools, and certainly can be roughly equivalent to savings placed in joint checking or savings in steps three and four. However, because these are often funded through workplace plans, they end up potentially taking precedence over individual checking or savings accounts.

When it comes to college funding, it typically is going to end up all the way back in Step 8. This is following the basic wisdom of the airplane oxygen mask: attach yours first before assisting others. While you might feel a desire or an obligation to help your kids go to college, you should not be giving away your own financial future to do so. Through no fault of your own, your kids will be younger than you, and will have ample time to build a career and make a living. You are likely to be decades ahead of them in this regard, and only have so much time to make up for lost time with regard to funding your future financial independence. If you can fund both your retirement and college at the same time? Terrific.

Where should our money actually be?

The challenge of cash management is that sometimes it’s more than just managing cash! For joint and personal savings, our normal recommendation is always going to be a high-yield savings account. As of this writing in February of 2024, that means banks that are paying north of 4% yields on their accounts. Whether checking offers an interest rate is less important since that account will turn over on a monthly basis. Once you’ve funded adequate high-yield savings, then for your 401(k), Roth IRAs, and other types of investments, you want to ensure you’re using low-cost index funds, which can be either mutual funds or ETFs. If you know how to pick and manage them, then you know familiar names such as the Fidelity ZERO funds, Vanguard, and iShares names. However, if you don’t have an education in portfolio construction or investment management, do yourself a favor and talk to a qualified fiduciary financial planner, such as a CFP® Professional.

What if it’s not for us?

Many readers will have read this whole article with a frown. “That’s not how we do it. Is Dan saying we’re doing it wrong?” No, and far from it! Whether you follow this exact system, or spend your time and money focused in other ways, the most important thing that you should take away from all of this is that if you are married or have a life partner, you are in a serious financial partnership. Don’t fail to see the forest for the trees!

Take the time to organize your finances, communicate and share your financial goals and concerns with each other, and work as a team to accomplish the financial outcomes you’re looking for. Too many couples avoid talking about money not because they don’t want to, but because they’re looking to avoid a fight. But much like any form of stress, avoiding the problem simply only makes it bigger with time. So take the first step and ask your partner to talk to you about money, be gracious and patient with each other, and work to build a plan to improve your financial outcomes.