Have you ever had this embarrassing moment happen to you? You’re in a grocery store in the chips and soda aisle, and some fellow is up on a ladder organizing a bag of Pringles on the top shelf. You’re looking for something that isn’t Pringles, and frankly isn’t even chips or soda, and you walk up to the fellow and ask “Hey, do you know where the such and such is?” To which the fellow on the ladder says “Sorry, no, I don’t work here, I’m a merchandizer with the Pringles company.” It’s all a little embarrassing but seems relatively harmless. You wander off in search of someone who does work at the store, hoping they can help you.

Now, you might be curious as to why this everyday bump in the road of errand running is the leadup to this piece. “What possible significance does this have?” You might ask. What if I told you that the financial services industry is no different? That, when you go to many financial institutions (the metaphorical grocery store), not only is much of what they might provide you based on products that they don’t actually create or provide, but that in fact, much of the shelf space in that store is bought and paid for by the product companies? That, in fact, entire “aisles” of the financial institution’s goods and services are, in fact, provided by those product companies, and that those genuine employees of the financial institution may have little to no say in whether you can buy anything else.

This week, we’re talking about shelf space in financial institutions; how this takes place, what the effect is on the options available to you, and ultimately, how the cost of this particular issue ultimately comes out of your pocket.

A Little History of Shelf Space

Before the concept of “shelf space” in the way we’re discussing it came to be, proprietary was the name of the game, and for the purposes of telling the story, we’ll analogize every big box financial institution you can think of under the name “Proprietary Products Financial” or “PPF.” When you went to PPF back in the mid 20th century, you were entirely unsurprised to see that every investment or insurance product “on the shelf” was PPF products. PPF Large Cap Mutual Fund, PPF Emerging Markets, PPF High Yield Bond, PPF Whole Life Insurance, etcetera etcetera. In this world, every employee of PPF you talked to not only proudly wore a PPF name tag, but a PPF shirt, jacket, and worked in a branch office with PPF over the door. They would gush and excitedly tell you about the superior performance of PPF financial products, and of course, would happily sell you PPF’s financial products for your every financial need or want.

Of course, time and competition are a funny thing. As Vanguard and other passive index product providers began to show strong performance, and it became more and more common in the public consciousness to recognize that expensive actively managed investment products and proprietary insurance products were often not just overpriced, but they underperformed, and served much more effectively at making PPF profits than making you money, despite you taking all the risk. So, PPF and all the big box financial institutions pivoted. They stopped touting the superiority of their proprietary products, though they still offered them. They changed their nametags from things like “PPF Product Expert” to “Financial Advisor.” They let their advisors create team names and operate under doing-business-as (“DBAs”) names like “Clarity Financial” and “Ultra Wealth Management” and so on. All of this was done under an industry term, “open architecture”, which was supposed to contrast with the historical “closed architecture” of a proprietary-only institution.

With the change to open architecture then came the exciting new possibility that the financial professionals working at a PPF could now offer investments and insurance products from other companies. At first, this was only a half-truth. While firms would open the doors to alternative investment options for their advisors, they would pay them significantly different amounts of money based on whether they used proprietary options or competitor’s products. Use ours? Get paid 80% of the gross revenue. Use theirs? 40%. So, while the architecture was technically open, the incentives were still significant to go out and sell PPF’s products, so long as the consumer was unaware or gullible enough to believe that by total happenstance, PPF’s products just happened to be the best!*

*They were not.

Of course, time continued its march and thus, the public continued to become better educated on the sleights of hand being played by PPF, and so eventually, PPF came up with a new idea. “Shelf space.”

How Shelf Space Functions Today

You see, the problem that PPF and other firms had identified over the years was that consumers didn’t like knowing about conflicts of interest. Mind you, not that consumers minded finding out about them, but that they didn’t like it to be so obvious. When the PPF “financial advisor” recommends a PPF product, the consumer is more naturally inclined to be suspicious. “Is this really in my best interest?” As time goes on, and both regulations and ethical obligational standards raised the bar to help mitigate some of the conflicts of interest, things like differentiated payouts began to shrink or disappear entirely at some institutions. Yet, PPF and the like continued to post record profits. How?

Shelf space is derived from a simple arrangement. A 3rd party fund company (who we will call “Greed Funds” for illustrative purposes) enters into an arrangement with PPF that PPF will receive either a multi-million dollar fixed fee every year to be distributed by PPF, or that the fund will pay PPF a percentage of the revenue it receives from customers who invest in Greed Funds via PPF. This is often dressed up as a “marketing fee” or otherwise laid out as simply “defraying PPF’s costs of distribution.” Cue a skeptical eyebrow, right? Because these revenue sharing agreements can amount to hundreds of millions of dollars a year. Don’t believe me?

- Edward Jones Disclosure (Highlighted PDF: 2023 Edward Jones Revenue Sharing Disclosure)

- LPL Disclosure (Highlighted PDF: 2023 LPL Revenue Sharing Disclosure)

- Merrill Disclosure (Highlighted PDF: Merrill Revenue Sharing Disclosure)

- Morgan Stanley Disclosure (Highlighted PDF: Morgan Stanley Revenue Sharing)

- Get the idea?

It’s not just a few dollars here and a few dollars there. Every single dollar of these fees is ultimately paid for by the client in the form of higher expense ratios in the investment products that are made available to them through PPF and big box firms; and these dollar amounts add up to hundreds of millions of dollars a year for these firms, all flowing out of the pockets of their clients. Of course, the irony is that the financial advisors at PPF may not all be aware (some are, some aren’t.) After all, as you’ll see in the disclosures, most of the times the financial advisors making the actual sales to clients aren’t compensated directly for these. “So it’s not a conflict of interest,” one might claim. Except money is fungible.

For example, XY Planning Network recently launched a corporate RIA beta test, and when it published its payouts for advisors, many in the investment management and advisory community scoffed. “Such high fees to affiliate with the RIA, and the payouts are so low! How does this even begin to compete?” The reason the fees are high to affiliate and the payouts are so low is because XY Planning Network is a fee-only organization, and thus, it won’t accept a single cent of revenue from investment companies and insurance companies, and thusly, it does not have enormous amounts of hidden “back end” revenue to help pay advisors who affiliate with it more.

So What Does Shelf Space Cost Me?

Instinctively, we all know that nothing a business does is free. Free shipping is an illusion created by baking the cost of shipping into the sale price. The free bottled water given to you by the receptionist at the spa is simply part of the price you pay to go to the spa. Even the holiday or birthday gifts and cards you’re sent are ultimately paid for by you as a customer. Yet, these can seem like nominal costs until you see the real numbers.

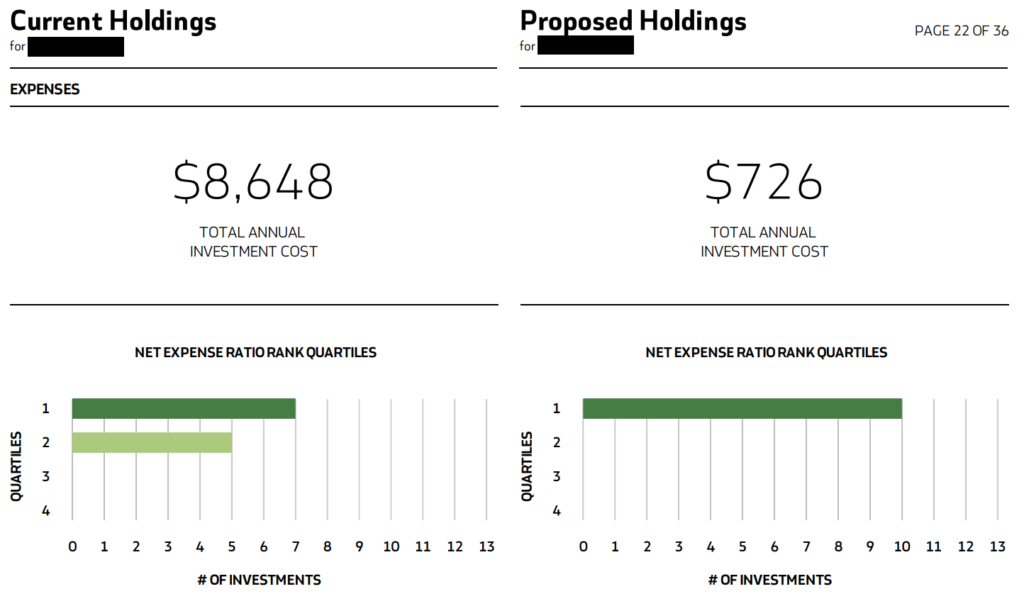

Let me give you an example. Last month, we brought over a client from one of the firms we showed examples of in the last section. The client had $1,502,544 invested with this “PPF” firm, all in assorted actively managed investment funds by companies disclosed on that firm’s revenue sharing agreement. The client’s annual investment product cost for using those investment products? $8,648. The portfolio we proposed putting them into made out of all passive index funds? $726.

Report from Fi360 Fiduciary Toolkit, investment expense ratio data 2/29/2024.

In comparing the two portfolios, the performance between them was effectively nominally different. So while the costs had been over 10x higher in the actively managed funds paying revenue shares to the PPF, they had gotten zero extra performance out of their investments. All the extra fees had simply gone to increase the payout to their advisors and boost the profits of the firm, while providing no advantage to the client.

Of course, you might say: “Well now that I know that, I’ll just ask for non-revenue sharing products.” Except that’s the kicker: You will end up paying anyway. When these firms are asked to invest in a company that is outside of their revenue sharing agreements, you’ll get one of two responses. Either:

- A) Sorry, we’re still doing due diligence on that [firm/fund/product] and we’re not comfortable offering it at this time.

- B) Sure, you can access that product on our super-ultra investment select platform. Additional platform costs are 0.25% per year on top of your advisory fee.

As they say, the house always wins.

So what do you do about it? Simply put: refuse. Do not pay additional investment and product fees for investment products that pay revenue sharing to the firm your advisor works for. Ask for disclosures. Demand exact dollar figures that not only your advisor will be paid, but the firm will be paid directly and indirectly if you invest with them. Have the advisor and their compliance officer sign off on a sworn affidavit under penalty of perjury that they are disclosing all of the fees and expenses to you. Or, simply do yourself a favor: Don’t shop at financial institutions or work with professionals whose firms exist to maximize their profit at your expense. You’re already paying for their expertise and advice. Don’t pay for their shelf space as well.

Comments 2

These “blogs”? are so interesting especially since my husband and I were so easily ripped off – LOL.

Honestly, many people are vulnerable. The government is not quick enough on the draw to protect many of us. And, who wants to read the fine print and even if we do, we can’t make heads or tails of it.

I think you might have mentioned earlier about high school financial classes and maybe a requirement as a college course. These days we may not need home economics (we can buy ready made meals) but how to manage our money, especially when it grows beyond our immediate needs, would be useful in living in our society.

Pingback: The Five Most Common Issues of “The Last Guy”