It might surprise you to learn that most of our clients worked with a financial advisor before they came to MY Wealth Planners. In fact, the vast majority of clients come to us with a grab-bag of ex-advisor’s insurance or investment recommendations. While early on, a financial planner might be surprised to see the goofs and bad choices recommended by other advisors, as time goes on, many of these mistakes simply become “oh look, another one of those.” Today, we’re sharing five of the most common mistakes and missteps in portfolios that we see at the hands of other advisors, and what we often recommend to repair the damage.

Common Issue #1: Unnecessary Commissions

Many of our clients show up with a bundle of investments that, simply put, cost too much. For example, while in the 20th century, a popular form of investment product was the mutual fund, many people still today are being sold a “Class A” or “Class C” share, despite the fact that these have been “out of fashion” for well over a decade at this point. These types of mutual funds can come with a sales charge as high as 5.75% upfront (meaning that $94.25 of a $100 investment actually gets invested) and a 0.25% “marketing and distribution fee” built into the fund’s annual cost, or as high as a 1% marketing and distribution fee. You can identify these sales charges and ongoing commissions by reviewing the name of your investment funds, for example: “Fictional Fund Large Cap Growth Fund A” or “Fictional Fund Large Cap Growth Fund C.”

While these charges and fees made sense decades ago in an era where “money management” was really reserved for the ultra-wealthy, and most investments were sold on a transactional basis for a commission, there is literally no good reason that anyone should pay an up-front commission to buy an investment today, or pay an ongoing trail to the salesperson for an indefinite period of time after the fact.

Even if you’re satisfied with the investments you currently hold, it’s important to note that nearly every fund family offers a no-load version of commissionable products. These products are identified by alternative share class identifiers such as “investor,” “institutional,” or “retirement,” often tagged with an I, Y, or Inv tail to the name. For instance, “Fictional Fund Large Cap Growth Fund I” or “Fictional Fund Large Cap Growth Fund Inv.” By simply transitioning from existing A or C shares to the no-load or institutional version of the same fund, you could potentially reduce your investment costs by anywhere from 0.25%-1% a year, saving you money and letting your savings compound all the more. Of course, share class commissions and fees aren’t the only thing to consider.

Common Issue #2: The Poor Probability of Active Management

For any client of a Wirehouse or broker-dealer, even if you are invested in no-load or institutional share class funds, you may very well find yourself with a bit of a sucker’s bargain on your hands. You see, as we’ve written about before, most broker-dealers and large institutional firms sell shelf space to investment product companies to be made available to their clients. This means that their advisors are only permitted to sell investments that have already paid their firm hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars to be available “in the catalog of options.” However, there are no free lunches, and consequently, the customer ends up paying additional fees and expenses for the benefit of those funds.

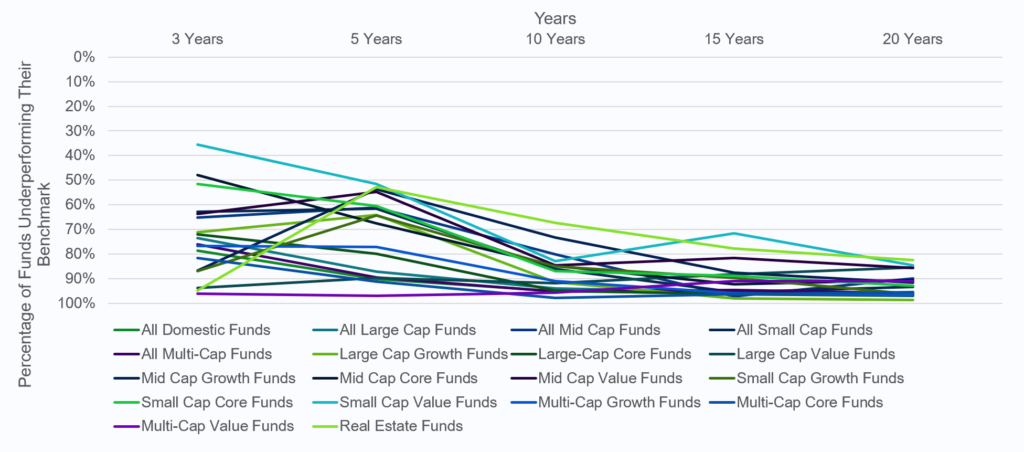

Yet, it’s never simply explained to the client that those unnecessary and high costs are simply a cost of doing business for the firms involved. Instead, they simply like to claim a statistical impossibility: The funds we recommend are all managed by the best and brightest portfolio managers who aim to successfully and consistently outperform the market in their area of specialty.” I’ve even sat in on a presentation by one such portfolio manager, who claimed, “We think indexes themselves are fundamentally flawed.” This was a curious statement since the manager had not outperformed his benchmark index, nor has he since he made the remark (2018). However, it’s true that in any given year, an active manager might earn his or her fee by outperforming the market net of their ongoing costs. Yet, as time goes on, the probability that they can do so year over year simply gets worse and worse.

But, by claiming that they can pick top-tier asset managers and by the power of hindsight to provide examples of managers who may have outperformed for the last few years, the advisors and their firms can claim that they’re good at picking these out-performers, despite the highly improbable odds that any individual manager they pick will do so, and the nigh-impossible odds that all of their chosen managers will do so. Ultimately, this leaves many clients who come to us with a pile of underperforming and over-priced investment funds, often held far longer than their best-used-by date.

Common Issue #3: Paying Too Much for the Wrong Thing

The customary benchmark fee for a $1 million dollar portfolio in the United States by a professional investment adviser representative and their firm is 1% for the management and advice service, before adding up or counting other fees. This 1% fee amounts to $10,000 per year at the benchmark and can be greater below a million or less above a million. The argument for higher fees under a million, particularly when fees creep below six figures, is that the expertise of the adviser is valuable, and therefore, they need to charge more to make up for the small asset base. This leads many firms to charge something like 1.5% for the first $100,000, then 1.25% up to half a million, and then maybe down to the benchmark of 1% past that point (just as an example, there is a huge variety of ways this gets done.)

Again, the argument for this is that the advisor’s expertise is valuable, so they need to be paid more to offset a small asset base. While I agree their time is valuable, I disagree that clients should overpay for it. After all, firms such as Vanguard and Betterment have essentially automated and commoditized investment-only fees for even small accounts, around 0.25% to 0.30% annually. When that’s the reality, one of the core reasons people then come to us as clients and are willing to pay us more is because the advisor charging more than 1% under a million dollars is doing exactly what those robo advisors are doing, and not a bit more. In other words, they’re paying more than 1% for a person to manage their investments instead of an algorithm, but they’re not actually getting any advice or additional services. Simply put, they’re paying 3x or more the cost without 3x the value. Thus, clients come to firms like MY Wealth Planners® because they want more than someone to manage their money, they want a fiduciary planner to help them build a plan and hold them accountable for accomplishing it, and they’re simply not getting that for the price they’re paying.

Now, to address what people should be paying, the latest studies on financial planning set the price of a comprehensive financial plan at a median floor of about $3k, whether the service is offered hourly, as a one-time project, or even as a subscription or retainer. Ultimately, this means that someone paying even 1% on their investment portfolio for “comprehensive advice” needs to be bringing at least $300,000 to the table to be managed, or otherwise they risk being a “sub-optimal client” for the average advisor, even when they might have valuable or complex financial planning needs that demand more attention.

Common Issue #4: Unnecessary Complexity

There’s an investment management personality in the finance world who loves to say: “Complexity is job security.” What he’s observing in practice with this statement is that often, you can find clients who are bringing portfolios with 15, 20, 25, or even 50 different investments in a single account. I even once came across a client with 98 different investments, despite the fact that 90% of the portfolio was concentrated in 3 proprietary mutual funds. The simple truth of the matter is that most people don’t need any more than a dozen or so funds, and often, the less the better. It can make sense sometimes to break up concentration in a big fund like an S&P 500 index fund by splitting it across two funds just to hedge the tiny risk that one fund might go off the rails, but it’s seldom going to make sense to break up the same S&P 500 index into a dozen different products mirroring the same index.

However, the same level of unnecessary complexity really starts to show up in said replication. Imagine a portfolio with an S&P 500 fund (SPY), an S&P 500 value-skewed fund (SPYV), an S&P 500 growth-skewed fund (SPYG), and a second S&P 500 fund or one that’s equally weighted instead of market-weighted (QQEW). Mind you, we’re not criticizing any of these individual funds but raising the question of “why?” What does investing in the same index four different times, in four different ways, accomplish? Simple: The appearance of complexity where none was needed or existed before.

In turn, being oversimplified can be a problem: A common joke on Twitter is “VTI and Chill” or “Vanguard Total Stock Market Index and Chill.” In other words, all you need is to buy a single fund, and you’re set for life. Yet, this misses an obvious point: A perfect portfolio probably isn’t a market-weighted index fund tracking most (not all!) of the US stock market, given that there’s an entire international stock market and fixed income segment of both the domestic and international market to consider. But, even the most diehard passive index investment adviser can demonstrate…

Common Issue #5: Poor Accountability

Let’s say that even the best financial advisor is “doing it right.” They’re not charging more than 1%, there are no commissionable funds in the portfolio, and the fees are reasonable enough that they’ve been doing financial planning. Terrific! Bonus question: By what means or method does the advisor consistently monitor the investments and report performance to their client? The most common answer we see to this question is simple: “Well, you get a statement every month or every quarter, and we have an annual meeting to let you know how well things are going.” Chummy, terrific, not a bad answer. Yet, when you push on the question ever so slightly, you find that this isn’t really that sufficient. After all, a bad investment can still be making money! Just, perhaps, not as much as it could have if it was being better monitored.

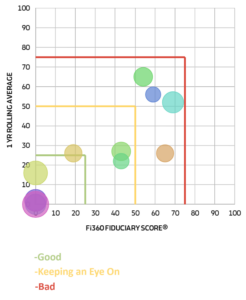

This is a scatterplot showing two sets of metrics: On the Y axis, a simple peer-percentile ranking where 0 is the best, and 100 is the worst of pure performance over the past 12 months. On the X axis, other peer ranking metrics such as Alpha (performance net of fees and risk), Sharpe (return per unit of risk), and annual performance in the past 1 year, 3 years, and 5 years as ranked by percentile. What we can see here is that while about 1/3rd of the investments are in the top quartile of their peer group in terms of performance and peer-to-peer comparison, the next 2 have gotten decent returns for the past year but have lagged the past five, and four of the investments are simply put: laggards compared to their peers.

Should a competent financial advisor have detected these flaws and rushed to replace them or head off their failures? Maybe. Not really. But here’s the observation on our part: None of our clients have ever been the wiser that they had a single loser in their portfolio. After all, even bad investments can make money, and if, in the annual meeting, the advisor says everything is hunky dory, how are they to know? The simple fact is that any advisor can be just as susceptible to the bias that they’ve done a good job. Heck, even we have a few investments we’re keeping a close eye on.

The key difference? We report this type of data to our clients every quarter in a written report, along with a plain statement of what those investments cost them and what we’re charging them, and provide a breakdown of the performance of each individual fund. The good news is we seldom have bad news to report, but the bad news is that there is always going to be some amount of bad news. No investment manager can promise to pick a winner every single time (see point #2), but being accountable for keeping a close eye on things month-over-month, quarter-over-quarter, and year-over-year is a meaningful element of accountability both because it’s the advisors’ job, but also because we as fiduciaries owe it to our clients to be so transparent.

What Do You Do If…

…if you see the problems of unnecessary commissions, the delusion of active management, too much cost for too little service, unnecessary complexity, or poor accountability in your advisor’s service? Simple, you start talking to other advisors. To a fault, we can all pick out the flaws in each other’s work (and there are always flaws, don’t let anyone tell you otherwise), so take the time to get a second opinion. We happily provide complimentary consults at MY Wealth Planners, but even if you don’t want to work with us specifically, you can always find other high-quality fiduciary financial planners at a number of sources such as NAPFA, XY Planning Network, or Fee Only Network. You can even read advisor’s client reviews at a site like WealthTender. So take the time to check your portfolio, kick your own tires, and get a second opinion if you need one. It’s only your life savings, after all.