The Oracle of Omaha once said, “Only when the tide goes out do you discover who has been swimming naked.” While the meaning of this colloquialism varies based on who’s quoting it and the circumstances thereof, today we’re thinking about leveraged portfolios. Specifically, the risks of leveraged portfolios and where it’s often considered risky or safe, despite the risks being equally salient to investors of all kinds.

What is Leverage in Investing?

Simply put, leverage is borrowing money to make an investment, or more specifically, to enhance an investment. By borrowing money, you’re taking on the risk of having to pay back the principal you’ve borrowed plus interest, but you’ve also potentially taken advantage of the possibility that you will see investment returns greater than the cost of borrowing, and consequently, will have magnified your returns beyond that which your own money affords you. Some classic “non-investment” examples of using leverage are student loans and mortgages.

When borrowing money to fund an education, you’re making the conscious decision to take on debt with the assumption that you will receive a return on that investment via higher earning potential, and in the case of a mortgage, you assume the costs of the mortgage along with home maintenance in the hopes that the combination of home ownership and appreciation will make the potentially greater-than-renting costs a good long term decision. While many Americans engage in both of these activities, both of them carry risk. Not all educations produce a return on investment (e.g., the trope of the philosophy major working as a barista) and not all homes appreciate in value.

In turn, leverage in the strictly investment sense is often thought of as being riskier. In the case of stock market trading, “trading on margin” is borrowing money to increase potential returns while also potentially taking on much greater losses. The number of people trading on margin is substantially lower than those who trade on a cash basis, but that’s not the case in other asset classes, such as real estate, where “borrowing on margin” or taking out loans for investment properties or development is the norm and not the exception. However, all this laymen’s explanation of margin and borrowing simply sets us up for the problem of the day.

The Tide Going Out

Over the past few years, it’s made the news and been a major item of attention that the Federal Reserve has raised interest rates, and consequently, raised the floor of interest rates on offer via private lenders. For those who managed to buy homes in the early teens or in 2020 or 2021 when rates were as low as they could go, the changes in interest rates are not particularly consequential. However, for those now seeking to buy homes or borrow money for any number of purposes, the costs of borrowing have increased dramatically.

From June of 2020 to June of 2024, the average 30 year fixed commercial mortgage rate has climbed from 3.13% to 6.99%, effectively doubling the cost of borrowing money in just a few short years. For example, a home purchased for $645,000 at 3.13% in 2020 on a 30 year fixed mortgage would cost its borrower $2,764.78 in principal and interest, while someone attempting to borrow $416,000 at 6.99% in 2024 would be paying nine cents more per month for 1/3rd less of a purchase price; to say nothing of insurance and property tax rates which have steadily climbed nationally and particularly in Boulder, Weld, and Larimer Counties with the recent history of fires and hail storms.

However, the story of interest rates increasing that we’re looking to tell today particularly focuses on investments that utilize leverage, and so herein we find a story of the folks who are swimming naked.

Who’s Swimming Naked?

In the investment world, there’s a funny little bifurcation of investment opportunities and how they’re regulated. Investment securities such as stocks, bonds, and investment products are regulated by the Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”). Commodities such as gold and coffee are regulated by the Commodity Futures Trading Commission (“CFTC”). And real estate is regulated by… no one. Well, not exactly no one. Real estate securities products such as Real Estate Investment Trusts are regulated by the SEC, but the buying and selling of investment real estate in a mom-and-pop manner, is a generally unregulated arena; at least insofar as the investment end of it goes, while of course housing and commercial real estate are subject to assorted state, county, and municipal rules and laws regarding fair housing practices, zoning, and so on.

However, the absence of regulation in real estate is a funny thing, because like all loopholes, someone out there will attempt to exploit it. Now, before we go on, let’s bifurcate this discussion into two groups: there are professional real estate development and management companies, and there are “build wealth through real estate” grifters. To be clear, we’re actually not going to talk about the latter group. Grifters are grifters and we know them when we see them (usually.) No, specifically we’re going to talk about real estate investment via professional real estate companies and syndicates.

Notably, these are companies that are not breaking the law. Rather, they are essentially small businesses made up of a collective of professionals and investors, in this case, the “general partners” and the “limited partners”, or “GP” and “LP”. The GP’s role is to identify real estate opportunities, get together the vendors and employees to build, enhance, renovate, or improve a new or existing property, and the LP’s job is to bring money to the table. Notably, because real estate carries so many tax advantages and opportunities to apply leverage, there is then often an extremely large amount of money being borrowed to fund the projects. However, the changes in the Federal Funds rate has put some of these companies in a tight spot.

How Federal Reserve’s Rate Changes Impact These Investments

Here an example of a typical syndicate or real estate investment offering might be performed is illuminating. Let’s say you want to develop a $20 million dollar piece of real estate, such as a self-storage facility. You’ve found the land you want to develop, now you just need $20 million dollars. Fortunately, you have a bank willing to lend you $10 million, but they need you to bring the other $10 million to the table. You personally have $1 million, but you need to fill the other $9 million in, so you put in your million and get investors to fill in the $9 million.

To do this, you need to create a pro forma illustration of how you think the investment opportunity is going to work. Pro forma is a fancy term for “forecast,” in finance terms. The pro forma is shared with investors, showing them your expectations for the project, including where investment dollars will go, what the estimated expenses and costs will be, and the anticipated return on investment for the project. If it looks enticing enough, and most importantly, it isn’t fraudulent, then you will have investors willingly giving you money for your project, and as long as everything goes according to the plan laid out in the pro forma, everyone is going to make money when the project is completed and then, ideally, sold to another investor or business at a profit above the cost of investing to build the property and operate the property over time. Huzzah!

Now, in many cases, part of the pro forma is an assumption that this project is not going to pay off the loan it took out as part of funding the project. This is because to maximize the return to the investors, paying down the principal of the loan simply means that when there’s a sale there could be more of a taxable gain, which is not what the investors want to see! So, many of these programs will utilize an interest-only loan for the project, which can resemble an “adjustable rate mortgage” in that the interest rate is set at the beginning but may change in the future if interest rates go up. Herein is where the tide going out is problematic.

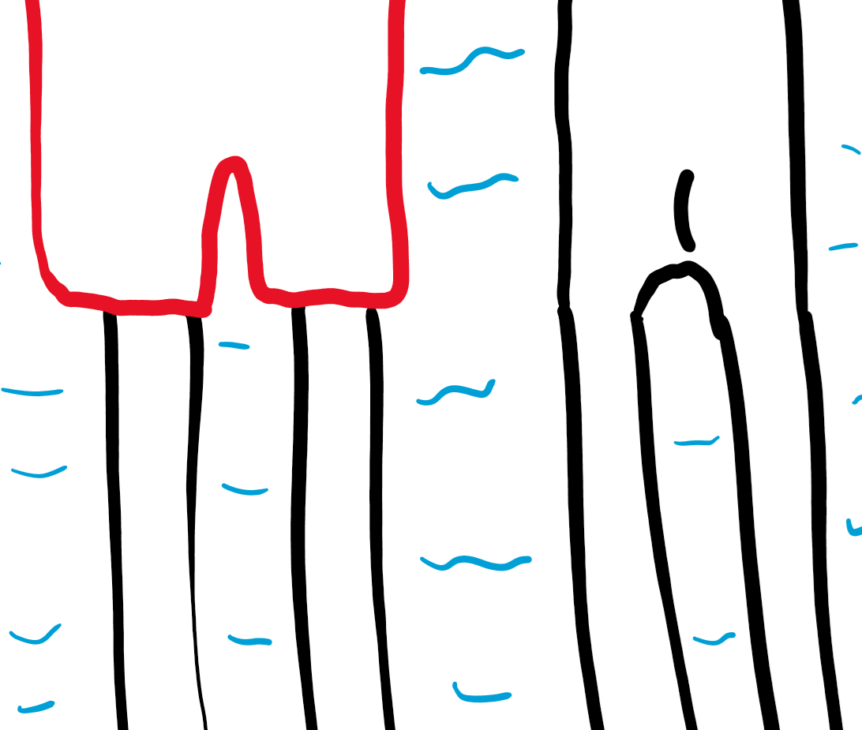

Let’s say the original pro forma showed a 10% expected rate of return and assumed interest rates of 6% from the bank lending half the money for the project, and that those rates would be consistent for the next five years. This would mean that the gross rate of return could be 8.49% after the loan is paid for. However, the Federal Reserve raises rates, and three years into the five-year project, interest rates have now popped up to 9%. This would mean that all things being equal, the expected return has declined to 5.5%.

However, there is an additional problem: this investment is supposedly a cash-flowing business (a self-storage lot, remember?) The problem this poses is: does the investment group have the cash on hand to eat the extra interest cost, or do they have the capital on hand to purchase a rate cap (a limit on the interest rate the bank will charge them) so that their cost of continuing the investment for the next two years doesn’t get out of hand? If they do, then they might be able to eat the increased costs, albeit that puts a damper on returns. But if they don’t have the cash on hand, then this can result in a capital call, requiring that the investors either fork over more money than their original investment or risk a degree of dilution of their ownership while other investors essentially “buy” a portion of their investment from them to meet the cost. Thus, an initial investor’s commitment of $200,000 might suddenly balloon to $250,000 to $300,000 to meet the needs of this investment, or forfeit the returns they were originally expecting.

Further, there is a question of the exit. Many such investment projects utilize the same assumptions for the build or renovation as they do for the exit. But what happens when the project is supposedly complete (e.g. the 5 years has run out) and the environment has changed. Many of the assumptions of the entire investment were based not only on the rate environment anticipated throughout the investment term, but also that buyers would be able to enjoy the same sort of environment for their purchase. But remember our 2020 versus 2024 home buying example earlier: will potential investors be able to afford to acquire this finished project at the price originally assumed? Or will rates push down the potential value of the investment, and consequently, drag even further on the return of the investor’s capital?

No risk, no reward?

Risk is a natural element of an uncertain world and investing is no different. All investments include risk, even an investment you might otherwise think of as being “risk free.” It behooves any investor to keep this in mind. When we as financial planners talk about expected rates of return, we’re always utilizing the historic returns and expected trends of the investments we’re talking about to help inform our expectations of both the risk and potential returns of those investments. Natually, this means that we’re confident but uncertain about outcomes, and while many clients are hoping we’ll say “the return here is guaranteed,” it’s more honest to say and thus we more often say, “I can guarantee at some point you will lose some money, but we’re optimistic that in the long term, you should make more than you lose.”

In the case of investments that rely on a pile of fundamental assumptions, such as borrowing interest rates, inflation, cost of materials and labor, taxes, and so on, the investor assumes additional and asymmetric risk. The good news is that this can mean that sometimes things work out better than planned and the return is all the greater; the bad news is that the opposite can come to pass. In the use of leverage, remember that returns are often magnified beyond what you could make by investing only your own money, the opposite is just as possible, and worse, you can end up losing money you can’t afford to lose.

Dr. Daniel M. Yerger is the President of MY Wealth Planners®, a fee-only financial planning firm serving Longmont, CO’s accomplished professionals.