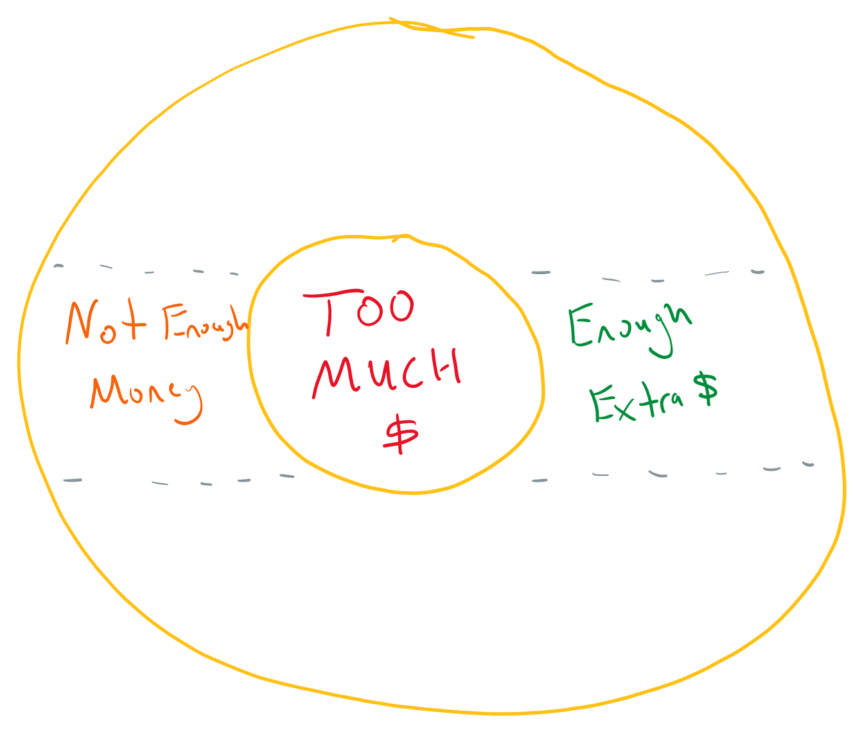

A common misperception by many about taxes is that if they make too much money, they’ll end up having less money than if they hadn’t made the money. This often arises from a misunderstanding of the marginal tax system, in which incrementally, your taxes increase as your income rises. The misunderstanding then is that if you’re in the 22% bracket, you must be paying 22% in taxes on all of your income, when, in fact, that rate only applies to the taxes in the bracket. Yet, there are specific circumstances where you can actually “make too much.” This doesn’t apply to tax rates themselves so much as it does to tax credits or qualifications for certain social welfare and tax programs. This causes a “donut hole” problem, in which someone may have a range of income that it would be better not to make, or they need to make more than the range of income to overcome the loss of another benefit. We’ll discuss two such examples today.

Electric Vehicle Tax Credits

For the past several years, both the Federal government and the Colorado state government have tried to incentivize people to buy electric vehicles. In Colorado, the 2024 tax credit is up to $5,000, with specific guidelines regarding the value of the vehicle; for example, vehicles under $80,000 in MSRP receive a $2,000 credit, while vehicles under $35,000 can receive a $4,500 credit. In the case of the Colorado tax credit, the credit is also refundable and can even be advanced to the car dealership in order to defray the direct purchase or financing costs of the vehicle rather than having to wait for your tax refund to show up next spring.

However, the same cannot be said for the federal electric vehicle incentives, which have two particular “cliffs” in place, creating two specific donut hole problems. The first cliff is based on your modified adjusted gross income and is capped at $300,000 for married couples, $225,000 for heads of household, and $150,000 for single filers or married filing separately. Consequently, there can be a scenario where, for a household right on the cusp of the relative line, earning as little as the single extra dollar that puts you over the line can result in losing up to $7,500 in federal tax credits; thus is behooves a married couple buying an electric vehicle not to earn more than $300,000 in the year they make the purchase.

Yet, there is another issue here. While the Colorado tax credit is both advanceable and refundable, the Federal tax credit is not. This means that while your federal tax liability can be reduced by up to $7,500 by credit, if you do not owe any federal taxes, then “surprise!” You’re not getting a single cent of the federal credit. Thus, for someone purchasing an electric vehicle in Colorado, it behooves them not only to be careful in the selection of their vehicle with regard to whether they will qualify for a larger or smaller refundable credit from Colorado (or any at all), but also they must underpay their Federal taxes all year, or risk “overpaying” their taxes by up to another $7,500!

Medicaid

For those individuals with less “first world problems” than buying an electric car, Medicaid qualification is a classic example of a donut hole problem. For a single individual in Colorado, their monthly average income must be less than $1,669 to qualify for Medicaid or $20,028 annually. Earn a single dollar more on average in a month, and you’re off Medicaid. Now, the “good news” at that point is that you could receive an Affordable Care Act subsidy that would pay the full premium for a silver-quality private health insurance plan. But what problems does that pose?

For a 50-year-old, the tax credit might cover up to $576.35 in monthly premiums, saving them up to $6,916.20 in annual healthcare insurance costs, which would be a significant amount if your income was only $20,029. However, even with the monthly premiums covered, this very same plan offered in Colorado would still leave you exposed to up to $4,750 in healthcare costs before your deductible was met, or up to $9,450 in out of pocket costs before your costs were capped. Consequently, the potential income donut hole between being on Medicaid and having enough extra income to cover the loss of Medicaid stretches from $20,028 in income to $29,478. In other words, you’d be better off making less than $20,028 unless you could earn at least $29,478!

Accounting for Donut Holes

These two examples exist on vastly different ends of the spectrum of financial concerns, but there are plenty of examples out in the wilds of tax codes. Whether it be the 3.8% net investment income tax that kicks in at exactly $200,000 for individuals or $250,000 for couples, the loss of income tax deductions based on earnings levels and eligibility for employer retirement plans (whether you participate or not!), or things as common as the child tax credit, it behooves everyone to be mindful of their eligibility for various credits and programs, and whether or not they could risk “making too much money” in a year by year circumstance.

Dr. Daniel M. Yerger is the President of MY Wealth Planners®, a fee-only financial planning firm serving Longmont, CO’s accomplished professionals.

Comments 2

Is there truly no way we can simplify the tax code? Is it special interests that garble up any attempt to make income taxes equitable? Reasonable? Sensible?

I seem to remember that you once discussed why a flat tax like 10% would not work or did you say it would? Ha!

Author

I personally would love a flat tax, but it sadly would be regressive and more harmful to lower income individuals than higher income individuals. Therein we get to play Plato: “What is justice?”