For several months, an economic analysis has explored the possibility of installing a “regional” minimum wage in the Boulder county area, which would technically be implemented as a county-level and city-by-city level minimum wage, including the cities of Boulder, Erie, Lafayette, Longmont, and Louisville. Curiously, as this study got off the ground, a video produced by the research task force asked for participation from local residents, local businesses, and local chambers of commerce, striking a tone that the municipal group needed to solve an issue for local residents and businesses. This reflects what some might call “throwing people in a hole and selling them rope,” but I digress.

It is not beyond acceptable debate to argue that some wages are too low, given the high costs of living in Boulder County. Conversely, some businesses cannot continue to operate if they are forced to increase labor costs without raising prices. For the record, the minimum wage discussion does not impact MY Wealth Planners whatsoever, as we currently pay no less than $9.41 per hour more than the state minimum wage on a salaried basis to employees, plus fully paid benefits. So today, we’re reviewing the study produced and highlighting key takeaways for some local economic insight.

Background

Before we get started on reading the study, a couple of items of note for readers who are looking to catch up on how things look today:

- MIT estimates that as of February 14th, 2024, a living wage for one adult in Boulder County, Colorado, is $26.36 an hour for one adult or $36.04 to support a household of two. The addition of children to the household increases the necessary income for a single head of household by $24.03 an hour, and then an additional $14.87 an hour for an additional child. For a family of two adults, that cost increases by $7.45 an hour if one adult is working or $9.38 if they’re both working.

- The de facto minimum wage in Boulder County today is around $18 an hour; some wages dip lower to $16 for lower-skilled or lower-effort positions, and some spike up north of $20 an hour for higher-skilled or harder forms of labor.

- The current federal minimum wage is a paltry $7.25 an hour, set in 2009.

- The Colorado state minimum wage is $14.42 an hour, and is indexed annually for inflation by the CPI-U index.

- Boulder County’s unincorporated land minimum wage is $15.69, and is locked in to increase to $25 an hour by 2030.

- The study in review encompassed responses from 98 focus group participants, 216 English-speaking community members, 37 Spanish-speaking community members, 131 English-speaking employers, 6 Spanish-speaking employers, and 252 business canvassing appointments in which researchers went into businesses to ask them questions directly.

- Notably, the taskforce had representation from each of the five cities, a representative from the Latino Chamber of Commerce rather than the more regionally representative Northwest Chamber Alliance to represent the business community, and representatives from the “self sufficiency wage coalition” as a political group (that has no website or other clear explanation as to its constituency), and the Emergency Family Assistance Association in representation of human services non-profit organizations.

Structure of the Study

This study is being conducted under the auspices of House Bill 19-1210; a law passed in 2019 that allows local governments to set their own minimum wage within specific provisions. Specifically, while local governments can set the minimum wage however they like, the year-over-year increases cannot exceed $1.75 per year or 15% of the prior year’s minimum wage, whichever is greater. In the context of the Colorado state minimum wage, this means the minimum wage could increase by up to $2.16 per hour year over year between 2024 and 2025.

The legal explanation in the study also provides for five sample recommendations; while these samples are clearly articulated as “a spectrum of possibilities,” they are quite clearly a guideline recommendation, as all versions except the baseline present significant increases to minimum wages, and each sample recommendation flows through the entirety of the 365-page report. They also all include a recommendation that once a change is accomplished, that going forward, minimum wages adjust by the consumer price index for all urban consumers (CPI-U), with specific reference to indexing by the Denver-Aurora-Lakewood area rather than the national CPI-U. They include:

- Baseline: Keep minimum wage in alignment with the state minimum wage.

- B1: Increase minimum wages by 15% annually until reaching $25 in six years (2030).

- B2: Increase minimum wages on a more graduated basis until reaching $28.98 in 2035.

- D1: Increase minimum wages by 15% annually until reaching Denver’s target of $21.84 in 2030.

- D2: Increase minimum wages on a more graduated basis until reaching Denver’s target of $25.32 in 2035.

- *It is noteworthy that these scenarios represent growth in wages above inflation (CPI-U of 3% in the study):

- B1: 6.41% over inflation.

- B2: 3.44% over inflation.

- D1: 4.04% over inflation.

- D2: 2.18% over inflation.

All recommended scenarios are predicted to result in the unemployment of approximately 0.4%-1% of the workforce, depending on which model above is adopted. In turn, the study anticipates that the sample proposals could produce anywhere from a 0%-0.17% reduction in the poverty rate by 2030, and up to a 0.5% decrease in poverty by 2035.

Overall Results of the Study

In a series of questions aimed at testing the respondent’s interest in a minimum wage increase, keeping status quo of increasing minimum wage by CPI-U based on the current state minimum of $14.42, or “other” responses. It’s noteworthy then that “increase” responses were oriented towards accelerating the minimum wage’s increase above and beyond the state minimum and CPI-U adjustment, that “no change” represented keeping that status quo, and the other responses are never articulated in the study as being particularly for, against, or otherwise.

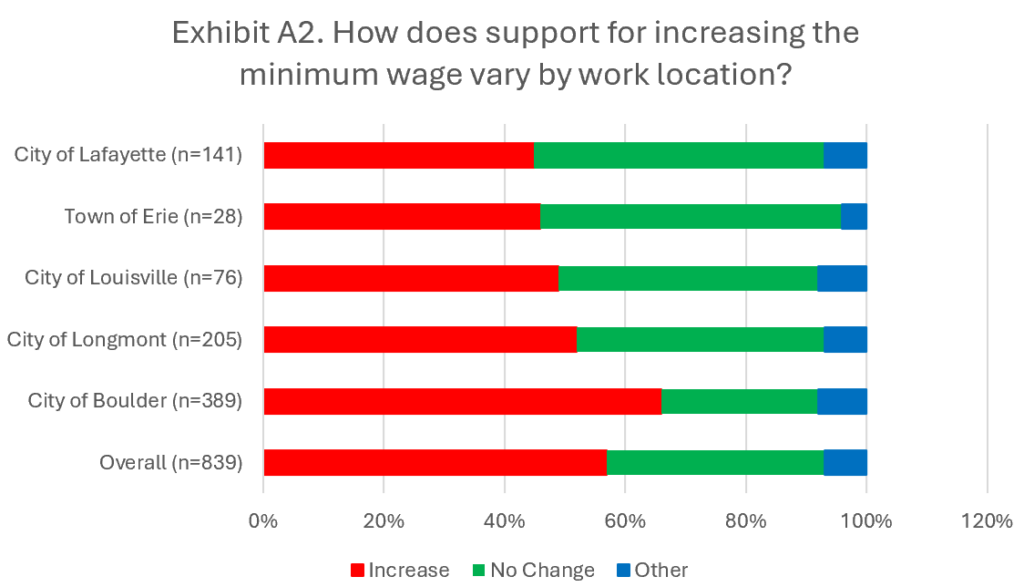

Upon first glance, it would appear that support for and against increasing the minimum wage is about equal across municipalities, with Boulder proving the clearest exception, which is unsurprising considering the astronomically higher cost of living in the city. However, when Boulder is removed from the equation, it ratios down to 48.92% in favor of an increase, 44.09% in favor of neutrality, and 6.98% with other ideas (pardon the rounding error). This is a valuable consideration, given that while Boulder has a population about 10% greater than Longmont, the consultants performing the study over-sampled Boulder by almost twice that of any of the other municipalities. In turn, with an n of 28 for the Town of Erie, it’s questionable whether they reached a threshold of statistical significance, as it seems improbable that a sample group of 28 people can speak clearly for a town of 33,104.

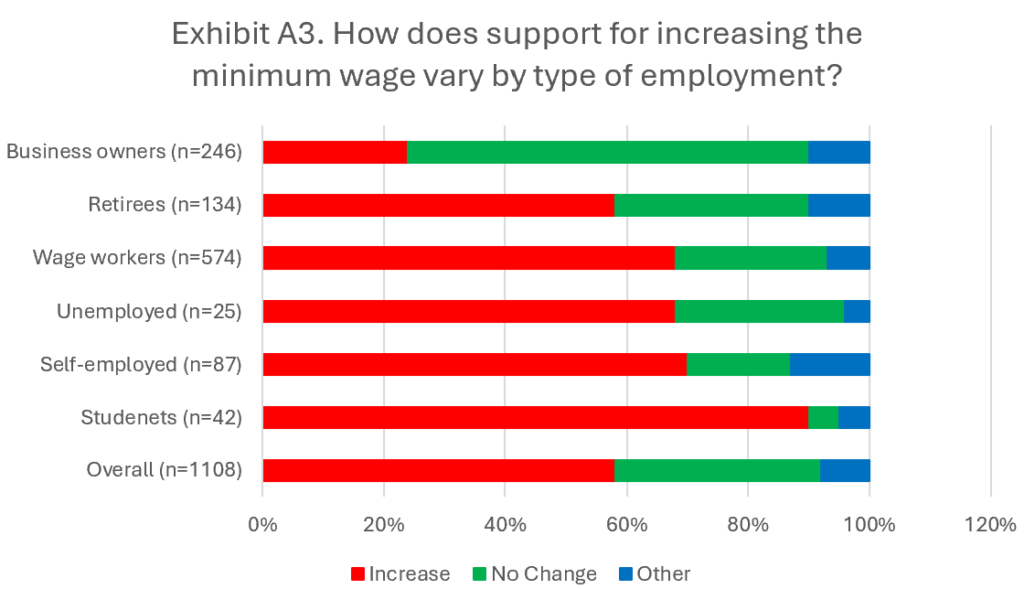

Further, when controlled for population representativeness, where 246 respondents were business owners and the remaining 862* were employees, students, self-employed, unemployed, or retired, the responses were incredibly disparate.

*Note that the N for the prior table was 839, whereas the N for the following table is 1108. No explanation for this is given in the study, but it can be assumed this is a result of missing data, which does not receive any FIML or probabilistic analysis to help account for the response rate gap. In fact, chart by chart and question by question, the study switches back and forth between different response rates, further driving home my concerns stated further below about the validity of the study.

As you can see, effectively, the unemployed, retired, and employed are substantially overweight towards a desire for an accelerated increase in the minimum wage, while business owners are overwhelmingly overweight away from a desire to see an accelerated increase in the minimum wage. This is particularly visible among students, who the report acknowledges typically work substantially fewer hours than full-time employees because of the subsidization of their cost of living via parents, and thus may wish to see their disposable income increased (though the study does not offer alternative explanations). It’s noteworthy that the only non-owner group that significantly deviates in the direction of wanting to see the minimum wage increase pace kept as is, are retirees. This is likely because of concerns about inflation caused by increased wages while many retirees live on a fixed income.

Finally, a few other descriptive statistics regarding the business owners (the charts for which are not replicated here) that suggest that business owner respondents do not, by a majority, favor accelerating increases to the minimum wage regardless of business size (30% for increasing while 61% are against increasing the minimum wage), with no clear trend-line between business sizes, which were broken into less than 10 employees, 10-24 employees, 25-49 employees, 50-99 employees, 100-249 employees, and 250 employees or more. Business owners represented approximately 31% of the overall response group, but made up significantly more or less of the response group city by city. 49% of Lafayette responses, 46% of responses in Erie, 39% in Louisville, 26% in Longmont, and 24% in Boulder.

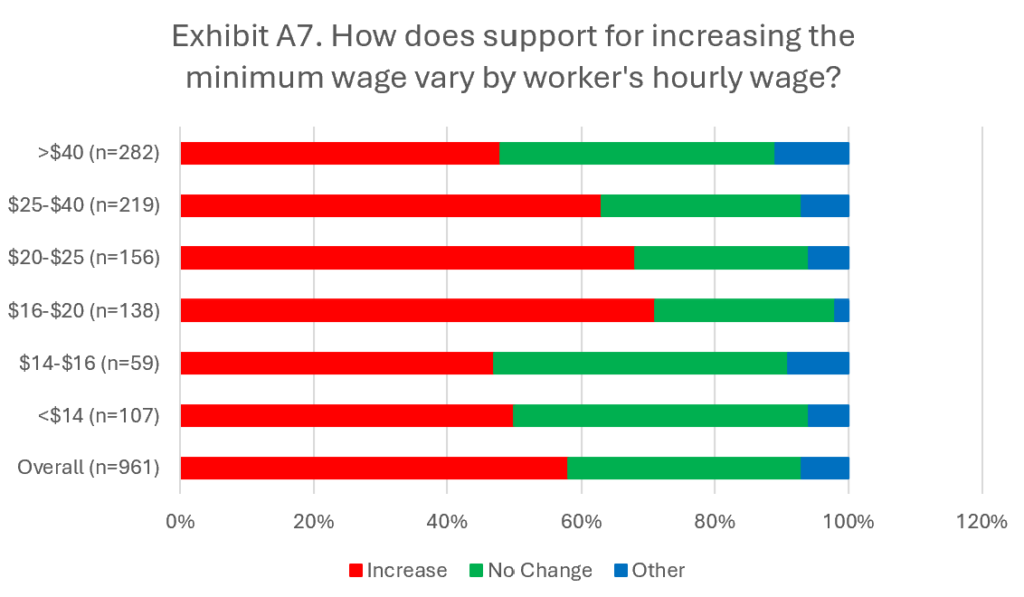

However, a very curious observation arises in Exhibit A7.

There is a spike in positive responses for increasing the minimum wage in those already earning around or about some of the proposed targets for the minimum wage increase over the next five to ten years, but those earning at or below the minimum wage are not a supermajority. In effect, those who might hypothetically benefit most from a minimum wage increase are some of the least likely to favor it, which might suggest some genuine concern in those groups about the security of their jobs if their company is required to raise wages and consolidate labor into fewer employees.

Takeaways from the Economic Analysis

Notably, the economic analysis in the study is not well explained. That is to say, there is a consistently vague format in which one to three paragraphs of summary explanation will be made about any given point of economic analysis, followed by a table or graph. Unlike a research paper which would lay out the formulas or methodology for the analysis, this study jumps straight to the conclusion. Consequently, we can only say in front of the notes below that the study “presumes” the following points:

- In the quoted feedback from both employees and business owners against accelerating the minimum wage, there was strong pushback against using the minimum wage as a tool to solve issues more in the purview of government, e.g., affordability and cost of living, particularly housing.

- Both employees and business owners expressed significant concern about causing a local inflation spike as some businesses increase prices to account for a forced increase. This likely has a strong relationship with the retired population’s responses that erred more towards a break-even “for/against” response than other non-business owner groups.

- For Longmont in particular, competition with Weld County stood out as a significant business risk, as goods and services could be significantly cheaper a mere few miles east. While some localized services cannot be replaced (e.g. when you dine at a restaurant, you eat at THAT restaurant), more mobile options may be able to compete by simply basing themselves across the county line.

- A sidebar comment: I recently spoke to my attorney about his thoughts on the economics of building an office building at some point in the future, to which he emphatically suggested building near Collision Brewing, across the county line. The key reason for this summarized? “I’m not worried about your business’s ability to deal with the regulatory burdens placed in Longmont and Boulder county, but you have to think about the potential impact on your potential tenants’ businesses.”

- Notably, the Longmont sub-report chose to omit responses from businesses and employees who earn or pay more than the minimum wage currently in order to hone in on responses from those who would be most directly affected by the proposal. However, this represents a clear bias in the presented responses, creating a missing material data issue in the study.

- The study supposes that, depending on the proposed scenario adopted (B1, B2, D1, D2 mentioned earlier), while payroll cost would only increase by 1.8%-3.1% across all industries, restaurants in particular would see increases in payroll costs of 12.9%-21.7% by 2035. It seems unsurprising, then, that restaurants were vehemently opposed to minimum wage increases, with many testimonials in the study reporting that servers were earning $30-$40 an hour and proposing as an alternative that tipped wages be permitted to be pooled across all staff, rather than driving up the tipped base-wage of servers via the alignment with the $3.02 tip credit (in which tipped minimum wage is allowed to be no more than $3.02 less than regular minimum wage in Colorado.)

- However, the economic analysis grossly contradicts itself later on. Specifically, there is a claim that the cumulative effect of the minimum wage on increasing prices would be no more than 0.058% to 0.094% by 2035 relative to the baseline. This seems incredibly improbable, given that the baseline increase relative to the proposals involves increases solely at CPI-U (approximately 3% in the study) versus the proposed increased rates, which in some instances involve increases of 15% year over year until reaching their objective, respectively reflecting 2.18%-6.41% in annualized increases over inflation. While wages don’t makeup 100% of the costs of doing business, it seems highly improbable that proposals that would increase labor costs by 2.18%-6.41% over inflation annually would not amount to a cumulative increase of 0.058%-0.094% over the next decade.

Summarizing

There’s an old political parable: “A coyote, a wolf, and a sheep are discussing what’s for dinner. The sheep proposes that they eat grass. The coyote and the wolf propose they eat the sheep. The majority wins.”

In reading this incredibly long copy-paste-ridden study (it could be about 100 pages, but they’ve copy-pasted enormous volumes of data so it ends up at a length of 365 pages), it’s very apparent that there is an inclination toward the parable’s moral. While there are numerous qualitative quotations clearly articulating the risks and concerns about increasing the minimum wage, the entire study has been framed around a comparison of outcomes relative to the baseline proposal in which the minimum wage continues to increase by the rate of inflation. The study takes great pains to emphasize contrasts between those who want to see the minimum wage increase and those who want to see the rise in the minimum wage continue at its current pace. These groups are, almost entirely, a de facto division between business owners (e.g., those who would directly pay the costs of the mandates) and the employed/unemployed (e.g., those who would potentially benefit from such increases).

This study will provide the means for anyone to confirm their priors. Those on city councils or in government who favor raising the minimum wage will point to a barely explained economic analysis and the democratic majority favoring increases in the minimum wage to argue for it. Those who are against it will point out that the votes for increasing versus leaving things the same are diametrically opposed and based clearly upon the financial interests of those voting (the aforementioned “who pays, who gets benefits.”) To its credit, the study repeatedly frames its findings as a consideration of tradeoffs, but whomever may read the study can easily find specific points to fit their argument.

Finally, a small academic critique

This is not an academic study. It would not pass peer review, let alone muster as a robust term paper. This study was performed by consultants, who clearly erred on the side of providing data vomit as their delivery format (365 pages to deliver perhaps two dozen pages of insights.) There are numerous issues in the study with representativeness, convenience sampling, and lack of randomness to establish descriptive statistics or models. Understandably, these are a byproduct of the budget and timeline for completing the study, as well as the potential difficulty of sampling the desired populations. However, it seems noteworthy that many reading the highlights of this study are likely to talk about it in terms of it being empirical or otherwise “the facts of the matter.” Nothing could be further from the truth, and it’s disappointing to see that the quality of the study suffers from these shortcomings, because there will be material economic and personal financial impacts as a result of what politicians opt to do with the study. Some people may lose their jobs, some businesses may go out of business, or in turn, some people may continue to struggle with the cost of living. A decision to do something is potentially just as impactful as a decision to do nothing, but this study is a poor foundation for making either decision.

As I said at the top, MY Wealth Planners is not directly affected by these proposals; we pay well above the proposed wages. However, it is noteworthy that many small businesses and workers in Longmont and Boulder County may be seriously impacted by the results of this study. And that, frankly, is a shame.

Comments 1

Thank you for the thorough review and discussion. I hope folks hear you.