Over the weekend I spent a great deal of entertainment time listening to a new podcast called “If Books Could Kill.” The basic premise of the podcast is that bloggers and podcasters Michael Hobbes and Peter Shamshiri read books sold at the airport, often made up of “pop science” topics such as behavioral psychology, self-help, political topics, and personal finance, and tear them apart for their bad ideas. It leans towards the liberal and has a general tone of glib incredulity from smart people reading stupid things and talking about how dumb those things are. While I won’t bore you with a deeper read of the podcast, I listened to most of it with an “8 of 10” sort of score, and then it dropped to a “1 of 10” score when the most recent episode made it clear that many of their glib takes were no more based in fact than the subject matter they were critiquing for being a-factual. However, this did inspire this week’s blog: the popularity of “pop science” in the discussion surrounding personal finance, and the many popular bad takes that pervade the financial ecosystem. So today, we’re talking about some of the most popular dumb ideas in personal finance, and why we should probably take them with much bigger helpings of salt than we might otherwise do.

The Pop Science of Behavioral Finance

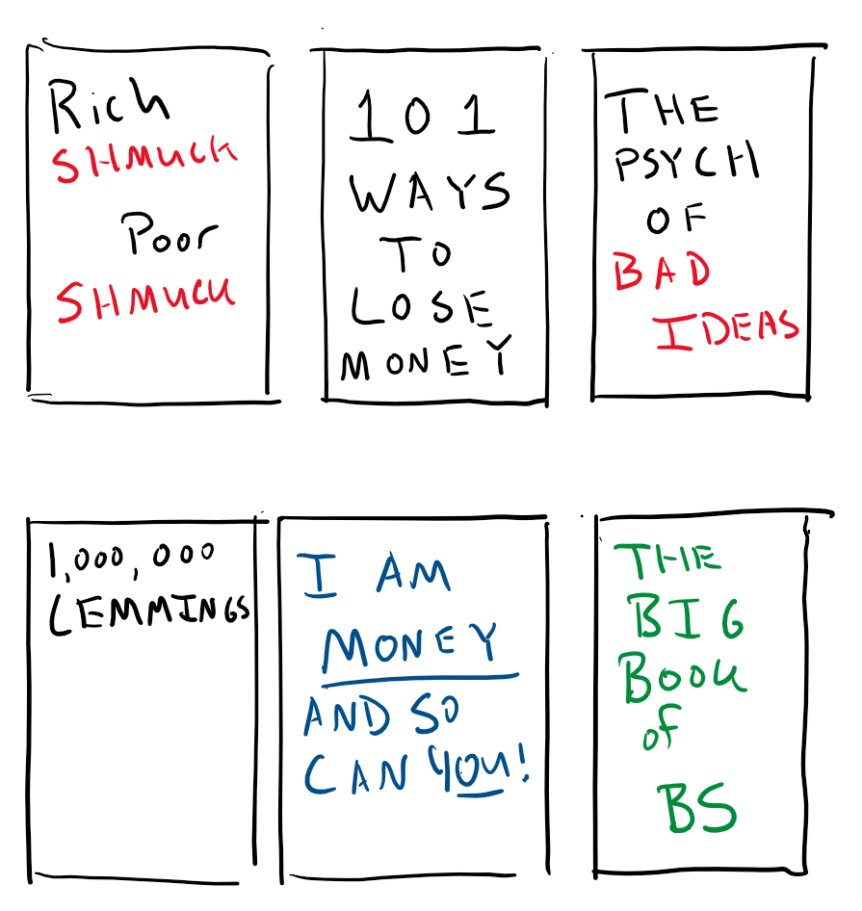

Behavioral finance, financial psychology, and other derivations of “the study of human psychology and financial topics,” are rife with bad science. The simplest basis for this phenomenon can be traced to a few basic things: First, many people generally find psychology an interesting topic, as evidenced by a plethora of pop psychology books (Daniel Pink, Malcolm Gladwell, and other repeat best-selling authors would fall into this category). Second, many people acknowledge that money carries with it a great deal of psychological bias and irrational behavior. Third, people love simply articulated solutions for complex issues. Behold, an entire cottage industry of behavioral finance books, bloggers, consultants, and classwork have sprung into existence over the past several years. You might wonder why this triggers such immediate skepticism on my part. “Dan,” you might say “Psychology is a big field with a lot of research, and finance is a big field with a lot of research. Surely there’s something to all of this?” To which I would say: “Not nearly as much as we’d like there to be.” The problem is that much of behavioral finance research is actually being elbowed into the seat from other areas of research. A great deal of what we discuss as behavioral finance comes out of economics and game theory, in which we assume perfect scenarios and then trace the rational response to those scenarios, or in which we perform equilibrium-oriented math and then observe how people will act adversely to what the equilibrium would suggest. In other cases, we look at behavioral studies around stress and financial behaviors and draw conclusions. And of course, a great deal of what we talk about in the space is simply made up, or researched to the depth of a Wikipedia article; perhaps quite infamously, the latest best-seller in the genre, “The Psychology of Money,” quite literally never references anything deeper than Wikipedia articles on its subject matter. It has sold three million copies and been translated into fifty-three languages.

“But where is the harm?” you might ask. “If people are being educated, perhaps not very well, but are nonetheless interested and entertained by the subject, surely it’s a worthwhile thing to see more of and consume more of?” Herein is the problem: In people’s fascination with and rush to accept passively and defend dogmatically what they’ve learned, bad ideas and suggestions percolate throughout the world, and a lie repeated often enough will be treated as fact. Take, for example, the suggestion by one “financial psychology expert” that you should never ask a client their financial goals in an initial meeting. The argument for this suggestion is that “research shows” clients don’t have a very good idea of what their goals are, and thus, financial planners should instead elucidate their client’s goals through a series of conversations aimed at revealing their goals through behavioral and financial analysis. It’s noteworthy that this research is never cited and there is no empirical basis for this claim. However, this suggestion seems reasonable on its face, but imagine then the same advice applied to any other field. You go to your doctor with a broken leg, and without ever looking at the leg or asking you why you’re there, the doctor asks you to come back for another three appointments to take various assessments to “determine your healthcare goals”; or you go to your tax preparer on April 15th (you procrastinator, you) and rather than quickly rushing to get your return done by the filing and payment deadline, your tax preparer hands you a 30-question personality survey to better understand your “tax planning goals.” You can iterate this silliness a myriad of ways, yet people will gobble up such an absurd premise as “don’t ask your clients their goals” without giving it a second thought, and proceed to build entire service processes around what is ultimately an utter waste of time for all but the most contemplative or confused clients who genuinely don’t know why they’ve contacted a financial planner, but for answering questions about their financial needs.

This same “silver bullet” thinking then pervades the constructs and advice that many people engage in with their finances. Read any number of self-help books and they will coach you endlessly to “envision” a better future, but give zero actionable advice on how to accomplish such a future. The same can be used in a self-defeating manner. “This book says that I’m money-avoidant, so the best thing I can do for myself is to make and spend more money.” One might find such advice healthy to a point, but whether you avoid having money or avoid holding onto money, the inverse advice to each condition might still result in being simply broke because the prescription has nothing to say about saving and growing money responsibly. This then, of course, leads us to the next great pop science lie.

The Pop Science of “The Rich”

No one can really describe the rich. It can be observed that even those Americans in poverty are likely “the rich” by a global standard, in which hundreds of millions of people around the world still burn human waste for fuel. Yet, even in our politics, the multi-millionaire politicians that run our society will often decry the rich for not paying a fair share of taxes, while simultaneously belonging to that same group they’re decrying. Of course then, “the Rich” are never us, but someone else with more conspicuous wealth than us. It is of great observational amusement to me as a financial planner that there is perhaps no whinier a profession than medical doctors on Twitter, who occupy the eighteen highest paying occupations in the United States consecutively (that’s spot #1-#18) before being interrupted by pilots at #19, and then returning with their co-workers, the nurse anesthetists at #20 (a citation, lest you think I’m kidding.) “We work too hard, we don’t make enough, and the student loans are killer!” So the outcry goes from million-dollar homes and luxury sedans. Cue the working class’s collective eye roll. But even with these necessary experts in healthcare decrying their financial lot, one must wonder whom all the books, videos, and podcasts are talking about when they talk about “the rich.” It can’t simply be celebrities and artists who “poof” into sudden fame and fortune upon the release of a best-selling single or a major movie roll; that’s simply a “sudden money” event from a turn of career fortune. So, of course, the advice when talking about the “secrets of the rich” cannot simply be to get cast with The Rock as your co-star in an action film (though if you can manage it, it’s a great strategy!)

However, the problem with the personal financial education “business” is that the secrets of the “average rich” rather than the famous or exceptionally rich, are rather boring. Earn great money, spend far less than the great money could afford you, save, and invest the rest responsibly in low-cost investment products. Not only is that advice boring, but it’s slow and feels unactionable. “But I already don’t spend more than I make and invest the difference. So why am I not rich?” Simply put, becoming rich without a sudden money event takes a great deal of time and patience. Yet that won’t sell substack subscriptions, thousand-dollar online courses, and get you a Netflix deal. So instead, the aged and useless grift endlessly iterates in the same structure: “[The Rich] have a secret that they don’t want you [the poor] to know. Follow me and [buy/subscribe/sign-up-for] my [book/class/seminar/day-camp/insurance-product/real-estate coaching/crypto scam] sales funnel and keep iterating until you buy everything I have or realize at some point that I’m just trying to extract money from you in return for selling you hope[ium].”

This all of course, sounds obvious when you hear it. Yet, there is no end to people who sign up for multi-level marketing schemes, real estate investment courses, cryptocurrency pump-and-dump newsletter scams, and endlessly iterate themselves into financial stagnation, or worse yet, financial ruin. I’ve even had a client, who has been financially successful, send me the newsletter of a convicted securities scam artist several times over the years, apparently forgetting that I’ve looked at it before and reminded them every time that the same scam artist is still a scam artist. It’s yet to sink in, because despite that rational knowledge, this same individual is consistently tempted by the idea that there’s a “better way” despite their already present financial success.

The Real Science of Wealth

If I were to write a personal finance book, it would take after the Stephen Colbert school of book titles: “I am financial literacy and so can you,” or some such. The book could be a single page followed by endless blank pages. It would simply say:

“The keys to building wealth are simple:

- Keep your expenses much lower than your income. If this isn’t possible, seek to increase your income through salaried jobs, hourly contracts, or a small business of your own invention that you are extremely confident in. Never do this by taking a sales job, particularly one that requires you to sell to your friends and family.

- Max out all available retirement savings options available to you and invest solely in low-cost index funds and exchange-traded funds. Do not regularly trade these.

- Do not take out loans for anything other than your home, education, or in rare cases that the cost of the loan’s interest is less than the high probability return on your investments. Never take out loans to make investments.

- Never buy an online course, book, product, or anything promising sudden wealth.

- Hire professionals for every aspect of your finances (estate planning, tax planning, investments) that you are not well-educated in and 100% comfortable with. Require that they all be fiduciaries, without exception, and in writing.

- Reread and repeat the above. Do not deviate.”

Every other page would be blank, or if really required, be a more detailed description of the concepts enumerated above. That’s it. Those are the secrets of the vast majority of the rich; the ones who aren’t on TV or on stage at concerts, but those who are just like us: ordinary everyday people who make an acceptable living and want to find the time and money to explore the things that make us happy. Even as a financial planner, I can say that almost anyone who responsibly follows steps 1-4 will probably be okay if they never reach 5 and 6, so long as they’re very honest about when #5 becomes required. Yet, as described before, despite the simplicity of these instructions and the time-tested manner in which they’ve built wealth for millions of Americans, we may yet always be tempted by just one more “special” and “good” idea that could set us apart in our never-ending quest to stay ahead of the Joneses.

Comments 1

Superior advice!

Since I have you this advice isn’t necessary for me now but I wish I had that years ago instead of struggling with a family and trying to manage our growing savings . I read books and took classes and couldn’t get to first base and lost money – lots of it.