One of the most common frustrations of a financial planner, really, of any financial professional, is when the client does things backwards. They make a big financial decision and take a big financial action, then afterward, come to the professional seeking advice on how to mitigate the consequences of their decision. “How was I to know that selling that condo for a million dollars was going to result in hundreds of thousands of dollars in taxes? Why didn’t you tell me that would happen? What are you going to do about it?” As the old expression goes, an ounce of prevention is a pound of cure, but in the context of taxes and consequences, many people are unclear as to when “consequences” are actually triggered. So today, we’re talking about the issue of Uncle Sam wanting his share, and teaching you just enough to know when you need to call your tax professional or financial planner before doing anything else.

Constructive Receipt – When Uncle Sam Wants His Share

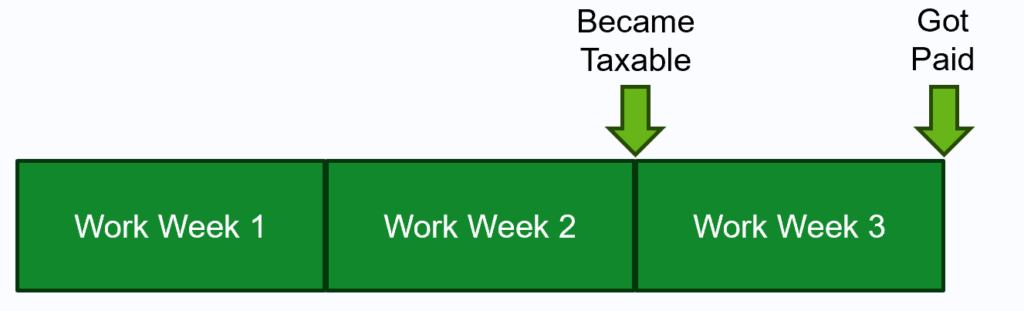

The basic answer to the question of when something becomes taxable is the “doctrine of constructive receipt of income” for most people (there are exceptions that apply to “accrual accounting,” but as promised, we’re keeping this to a basic applicable level.) Succinctly, constructive receipt triggers when you attain an inalienable right to receive income. For example, let’s say you’re paid every other Friday, but your pay stubs always reflect the work you did two and three weeks prior to the Friday you are paid. For taxpaying purposes, the income became taxable at the time that you finished your work last week, not on the day that you receive your paycheck. For the visually inclined, see the diagram below.

Fundamentally, from the viewpoint of the government, this mechanism needs to exist. If your income tax was based upon the literal receipt of your payment, then someone could have a handshake agreement with partners, vendors, or employers, to simply withhold payment until a more convenient time. Hence, the doctrine of constructive receipt exists to ensure that it’s not “when you get paid” but “that you will be paid” that triggers income, and thus, the potential for taxation.

What matters to anyone concerned about reducing or mitigating a potentially substantial tax bill is this: They must plan ahead before constructive receipt is triggered. Once constructive receipt is triggered, other than contributions to retirement plans and some other very limited and narrowly tailored spots, there’s little that can be done to reduce the taxability of the income.

Deferral of Income

That said, there are many mechanisms in the marketplace of finance that can create a deferral of income. A popular version is the somewhat obviously named “deferred compensation.” Now, this term can be a bit confusing because there are actually two forms of deferred compensation. The first is a 457(b) plan, which is typically used by municipal and state employers. Succinctly, those are much more like a 401(k) or 403(b) retirement plan. So here, we’re talking about a “non-qualified deferred compensation plan,” which gives employees control of when to receive income. It’s noteworthy that these plans are not magic: they are simply leveraging the doctrine of constructive receipt through well-established legal safe harbors. When an employee elects to defer some of their income into a deferred compensation plan, they are able to push taxation into the future because they are triggering another important principle: a substantial risk of forfeiture.

One of the conditions of constructive receipt is that the recipient is absolutely and unquestionably entitled to, and will, barring an extreme circumstance, receive their income. However, there are numerous conditions that can create a deferral of otherwise “assured” income, the most important of which is the substantial risk of forfeiture. That’s not a fancy turn of phrase, it’s quite literal in its meaning: That there is a significant and material risk to the recipient that they may not, in fact, receive their income. In the case of a deferred comp plan, this is achieved through one or two mechanisms: First, their deferred income may be lost if they leave their employer too soon, thus, creating a substantial risk of forfeiture. The second is that the employer may not have formally set aside the money for their deferred comp, or may hold it in a manner that makes it subject to the creditors of the company, meaning that it may be lost in a lawsuit, and thus, the employee is perpetually at risk of losing the income until they actually receive it.

Tax Deferral & Tax Advantages

Anyone who has ever watched an old “Pop Eye the Sailor Man” cartoon will remember the character of Wimpy, a timid but audacious man who would claim without hesitation: “I’ll pay you Tuesday for a hamburger today.” While Wimpy was then often the victim of the antagonists of the cartoon, he was onto something.

This brings up the topic of retirement plans. Notably, retirement plans have significant creditor and bankruptcy protection conditions applied to them. In turn, retirement plans have strictly enforced limits for contributions, ensuring that most Americans can only shelter so much of their income from taxation in any given year, and even over a lifetime. There are some extreme examples, like Peter Thiel’s five-billion dollar Roth IRA, but for most Americans, retirement accounts represent a meaningful but relatively nominal safe harbor from taxes. Even still, a clear understanding of the mechanisms of tax deferral and tax advantages is important. Simply put, the question with all retirement savings accounts is this: “Pay now or pay later?” Traditionally, retirement accounts and pension plans have taken the “pay later” route. This has involved giving people a tax write-off today in order to reduce their taxable income today, leaving more money in their pocket, in return for an obligation to pay taxes later on in retirement. The mechanism between point A, saving, and point B, spending the savings, is tax deferral, in which there is no ongoing taxation of the investments put into a tax-deferred retirement plan, but a recognition that every single dollar will be taxed in retirement.

In turn, with the advent of Roth accounts 26 years ago, the second option of “pay now” came up. In this case, we’re deliberately triggering constructive receipt on current income, paying taxes, and receiving a promise by the government that those dollars, and any dollars yielded by investing those dollars, will never be subject to taxation again.

1031 Exchanges, Depreciation, & Recapture

A popular topic among investors, particularly those in the real estate space, is that of 1031 exchanges. Simply put, the government has provided an opportunity for people to sell certain assets and buy similar assets without triggering a full capital gain on the sale of the first asset before buying the second. This was originally intended to make it easier for companies, particularly manufacturers of goods, to make purchases of plant and equipment and exchanges of no longer needed equipment for updated equipment, without having to deal with substantial tax consequences slowing down the engine of industry. However, 1031 exchanges apply to many assets, such as residential and commercial real estate, but most importantly, only to real property. There’s no trading of ideas, for example.

A 1031 exchange allows an individual to identify a replacement asset before the sale of an existing asset, and to transfer some or all of the basis from the purchase of the first asset to the second asset, without incurring a full taxable transaction on the sale of the first asset. This serves as a form of tax deferral, though some exchanges will trigger a degree of tax, depending on the disparity in value between the first and second assets. Still, this mechanism is often paired with the depreciation of substantial assets such as buildings in order to generate greater levels of tax-free cash flow and to accumulate wealth over time. Yet, there is no such thing as a free lunch.

While 1031 exchanges and depreciation serve as a valuable mechanism for deferral of taxation, the key word here is “deferral,” not its enviable cousin, “elimination.” Ultimately, somewhere down the line, every dollar of deferred capital gain or depreciated value of an asset used as a write-off, will ultimately be captured at the final sale of the asset or chain of assets. While the deferral of income can be meaningful, and strategically timing the recapture of deferred income can result in lower tax rates paid in the future than paid today, it’s important to understand that you cannot retroactively apply 1031 exchanges or depreciation, but must meaningfully plan for it ahead of time and keep strict documentation and compliance with the requirements of each tax deferral tool.

Imputed Income

Finally, there is the issue of “imputed income.” I recently had a business owner expecting a multi-million dollar windfall tell me that they planned to buy some of their employees cars. “That way I can give them a bonus but not have them pay taxes!” It was a lovely idea, but as I pointed out to him, if he does that, he’ll start to have to record imputed income on their payroll for the personal use of the company vehicles, thus giving them a car, but reducing their take-home pay by hundreds or thousands of dollars a year.

Imputed income is the taxation of the implied value of non-cash compensation. This can be the use of company cars, free meals, a company cellphone, the use of a company’s real estate assets for personal uses, and so on. Many business owners make it a practice of passing personal expenses through a business to reduce their income, and while it seems like a smart tax strategy, it can actually be a major landmine in their tax plan, particularly if they are audited. The same applies to employees who may receive stock options, paid gym memberships, or other perks. Fundamentally, if the thing the employee is receiving is not for the convenience or necessity of the business, then it’s simply a paycheck by another name, and taxes can apply. This can double up in cases of things like equity compensation or incentive stock options, where alternative minimum tax can be more easily triggered, despite employees potentially not having received a single actual dollar because of the doctrine of constructive receipt’s interaction with imputed income. “Just because you haven’t cashed in your options, doesn’t mean that they aren’t worth something.”

Bottom Line

As we said at the top: An ounce of prevention is a pound of cure. Everything we’ve discussed today can be a meaningful and important part of your financial plan, but only if it’s done right. Look before you leap, think before you speak, and before anything else: Call your tax professional and financial planner as needed.