At MY Wealth Planners®, we are a Fee-Only Financial Planning firm. This means we are paid directly by our clients and no one else. This is an advantage to our clients for an obvious set of reasons: fee transparency, reduced conflicts of interest, and in many cases, lower costs to clients. However, when the public is asked to compare financial advice companies, they have a hard time differentiating between them, the services they offer, and the cost of those services. A recent survey even found that the SEC’s new “Regulation Best Interest” was perceived by the public as being a higher standard of conduct than the Fee-Only “Fiduciary Standard”, even though regulation best interest is a significantly lower standard of conduct for brokers. Today we’re reviewing three ways that Fee-Based firms are able to add profit at their client’s expense to their business models, how and why it’s legal, and what you can do about it. To help illustrate, we’ll be showing you three real-world examples of these expenses and comparing our own business model to explain the difference. Before I go on, let me be clear: if you have a fee-based advisor right now, he or she is probably a good person. These are all issues caused by the advisor’s firm, not them as an individual, though they might directly or indirectly benefit from these issues, and that shouldn’t be forgotten.

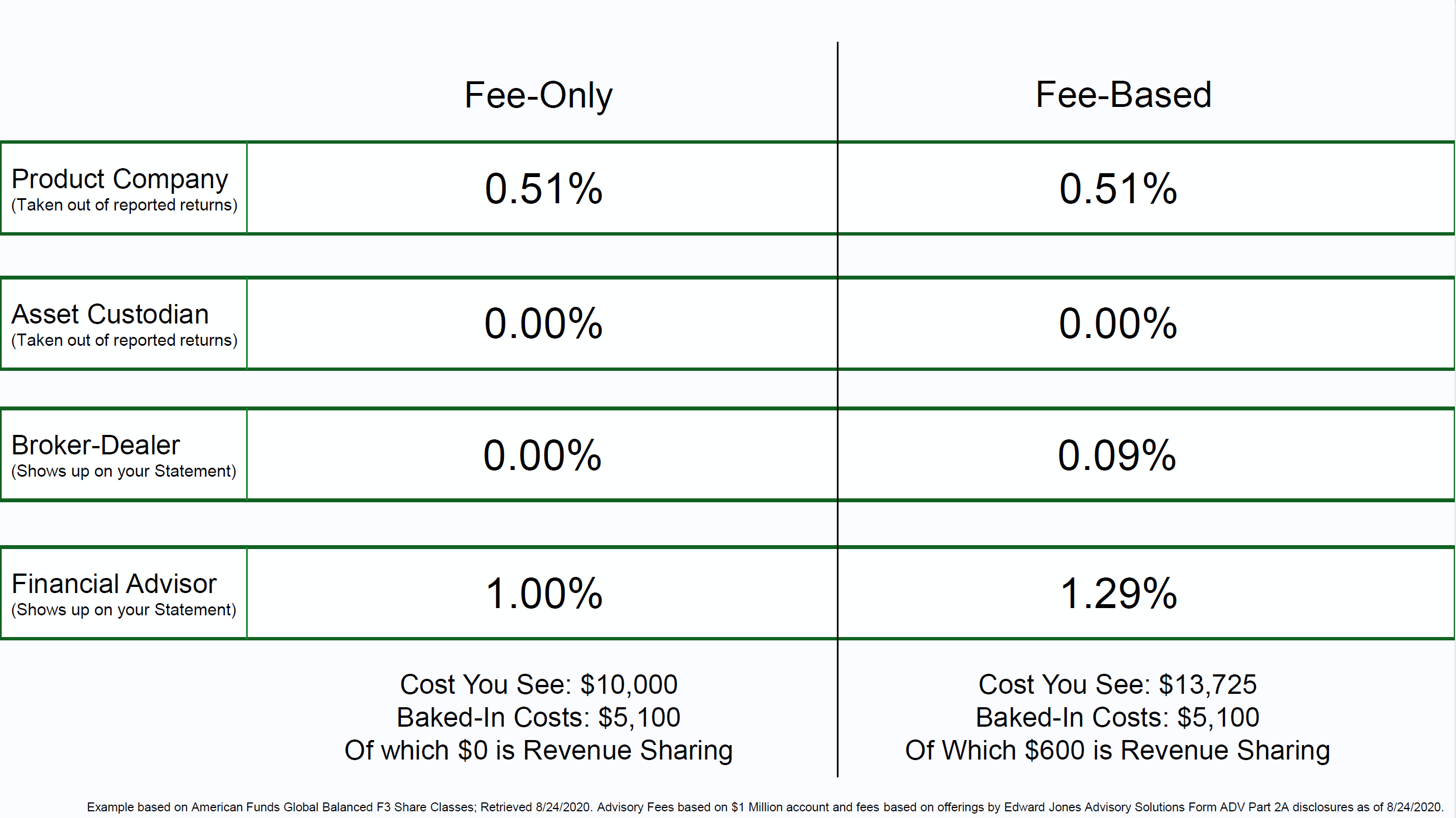

Revenue Sharing

Revenue Sharing is an extremely common practice in the financial services industry. The practice is often known as “buying shelf space”, in which firms pay money to advisory firms to offer their investment products to their customers. While advocates of revenue sharing say that the advisors don’t receive any part of the payment and thus are “conflict-free”, this isn’t the truth. The revenue-sharing fees are used to defray the cost of operations, benefits, and compensation for financial advisors, allowing firms that accept revenue sharing to pay their advisors a higher amount in direct or indirect compensation. Further, some large advisory firms are structured as partnerships, and the advisors working for them do directly enjoy the profits of revenue sharing in their take-home pay. Revenue sharing is structured in many different ways, with some firms receiving hundreds of thousands of dollars per year per fund company for the shelf-space agreement, while others charge upward of two-hundred and thirty-four million dollars a year on a percentage of revenue basis. Defenders will point out that revenue sharing isn’t paid directly by customers, but again, this doesn’t stand up to scrutiny. Companies like Vanguard refuse to pay revenue sharing agreements and have been stricken from the investment catalog of many financial advice firms, while other companies have simply raised their investment management fees to cover the revenue sharing agreements. Ultimately, what money comes out of your investment portfolio in the form of investment management fees represents the total cost of doing business for the fund companies and their profit margin. Here’s an example of how a revenue-sharing agreement can pop up in your own portfolio.

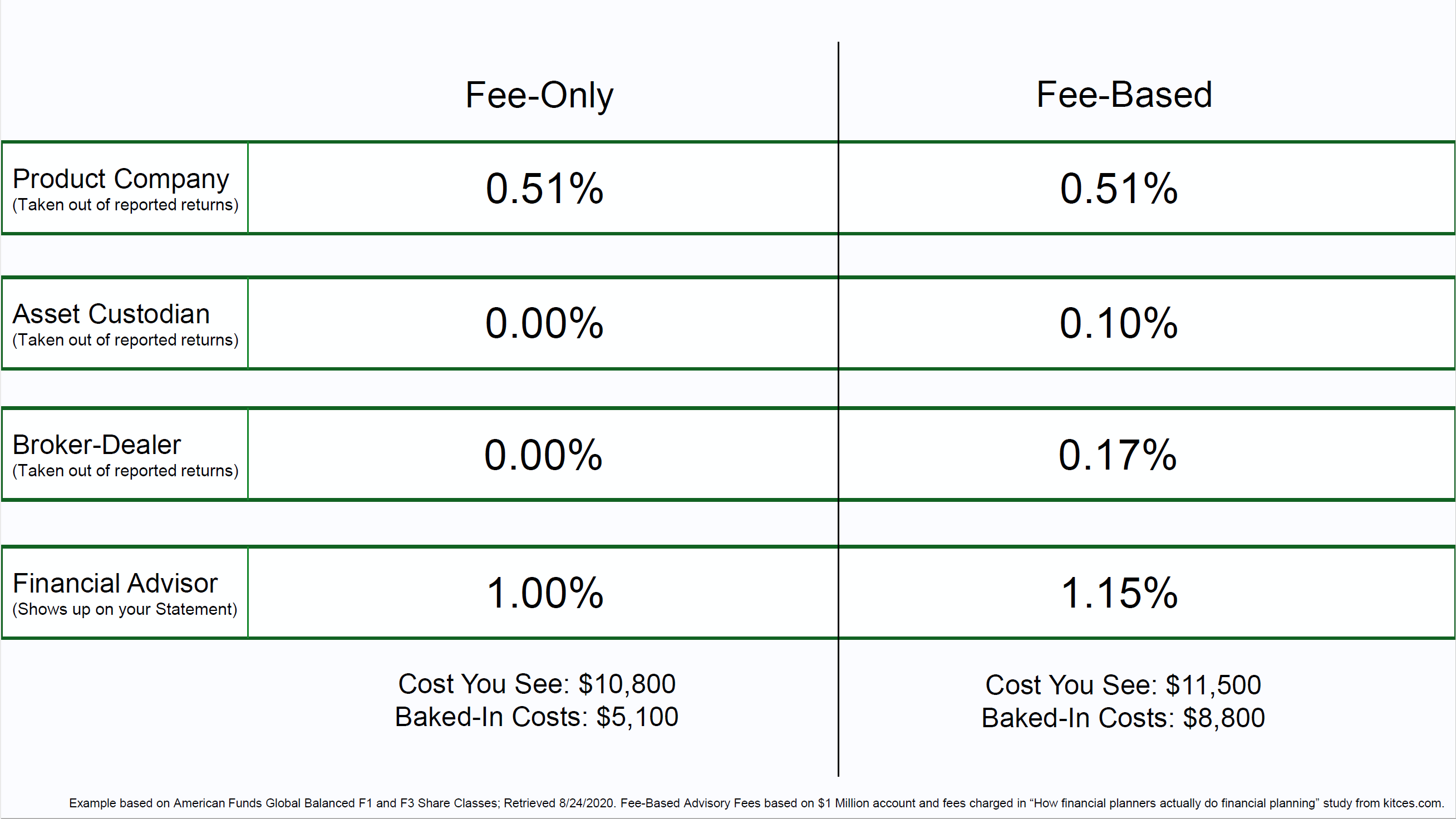

Share Cost

Another subtle way that consumers can end up holding the bag for additional expenses is through Share Cost. Mutual Fund companies offer a multitude of investment funds that provide a variety of investment objectives and portfolio mixes, alongside different ways of paying for the funds. Some funds are commission-based, taking a slice of the initial investment off the top to pay the broker for selecting the investment. But more difficult to detect are the differences in the share price. A fund bearing the same name as its brother save for the share class can easily cost over a hundred percent more simply by passing costs directly onto the investor rather than bearing the cost of doing business directly. In fact, a study in 2019 found that investment companies that started as investment brokerages directly favor using the institutional share classes of funds that they also recommend on a commission basis in their Fee-Based portfolios. These funds often contain the same revenue-sharing agreements, and are even more often the source of SEC fines, amounting to more than $6.6 million dollars per investment company per year over the past decade. Not that a $6.6 million dollar slap on the wrist can disincentivize agreements that add up to hundreds of millions per year. In the example below, we look at the American Funds Global Balanced Fund F-1 and F-3 share class. The F-1 share class carries additional costs for marketing expenses and “sub-agency transfer fees” while the F-3 doesn’t pay these expenses and relies on the investment firm to cover the costs. While the cost you see is nominally different on average, the baked-in cost is 72.54% higher, and the only way to detect the difference is the number 1 or 3 next to the share class!

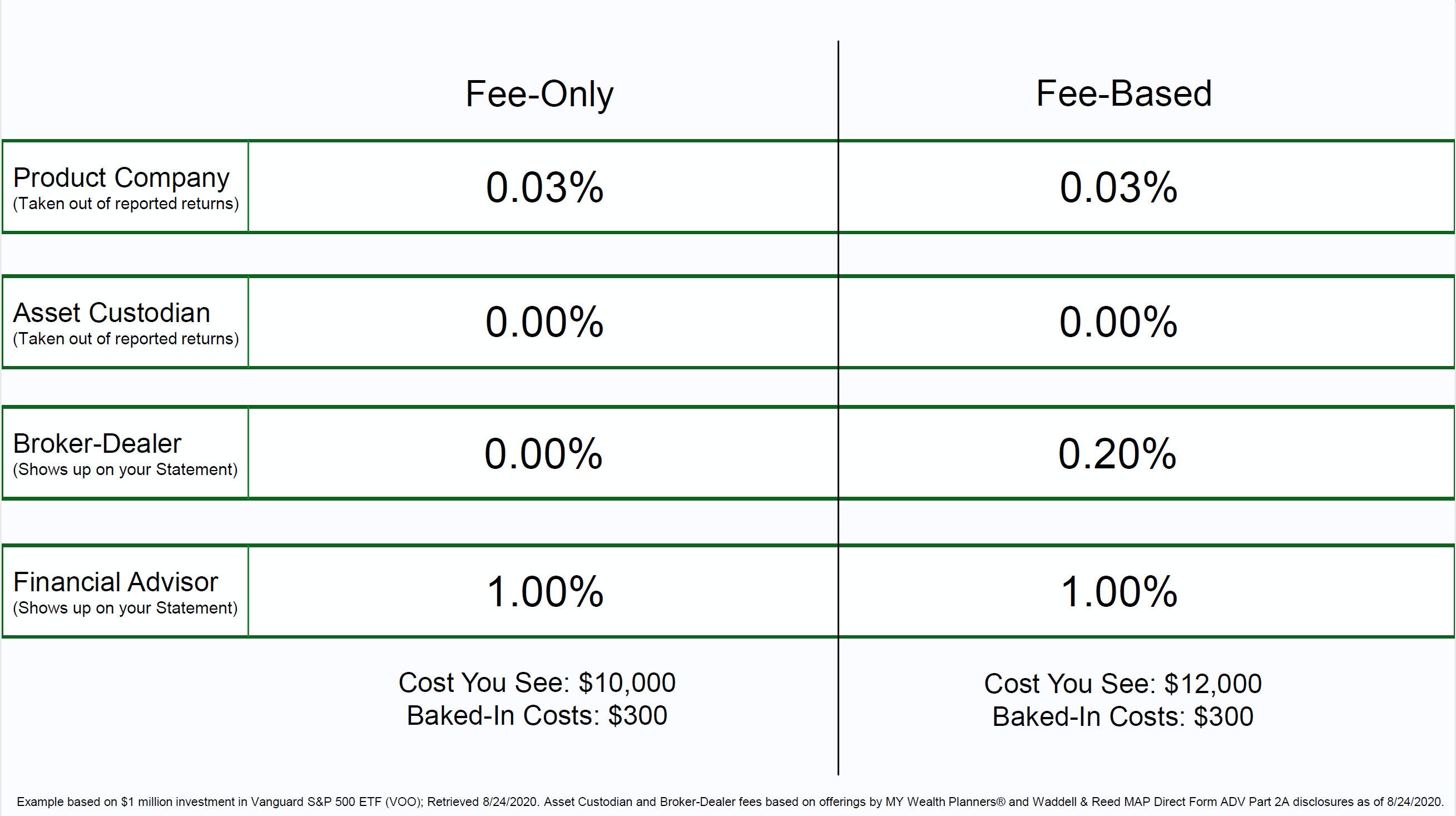

Sponsor Fees

This last fee is a perfect example of an “unnecessary evil”. Some firms attempting to avoid regulatory scrutiny are at least honest that they overcharge their clients, and this often shows up in the form of a “wrap fee”, also known as a “sponsor fee” or “platform fee”. In this case, the firm is transparent with clients and explicitly charges an additional fee for the service of holding investments on the platform. While this isn’t to say that the firm charging it doesn’t have costs it’s covering by charging the fee, other firms don’t mark up their services arbitrarily. In the following example, we look at a comparison of investing in a single exchange traded fund. Under MY Wealth Planners® current platform, this costs clients nothing other than the investment management fee for the product itself and the investment advisor fee charged by MY Wealth Planners. Under our previous hybrid platform, to offer the exact same fund required a “Sponsor Fee”, which simply existed to offset the loss of revenue because Vanguard wouldn’t permit revenue sharing.

How is this legal?

Investment industry regulation is a tricky thing. While the SEC has been cracking down on firms that double-dip their clients by both charging investment fees and 12b-1 “distribution fees”, the SEC generally stays out of the business of telling companies what they can and can’t charge (though they take a critical eye toward firms charging at the far expensive extremes relative to their competitors). Yet, in an industry where it’s customary for small accounts (those under $1 million) to pay all-in expenses close to 3% a year, that means that a firm has to be particularly egregious to draw ire from the regulators. Further, regulators rarely examine the all-in cost to clients, rather paying more attention to the individual components of the cost than what they add up to. While it is customary for a firm to charge clients up to 2% on the investment advisory fee, the regulators won’t bat an eye if the client also pays over 1% on the investment product costs, nor will they care if a significant portion of that product cost is then also paid to the Fee-Based firm. And while advocates will still say this doesn’t affect the quality of investment advice given to the public by their financial advisors and that regulation best interest protects customers from bad advice, none of these protections keep the advisor’s firms from limiting the advisor’s choices to the most profitable options. From that point of view, it’s considered Joe Public’s fault that they didn’t know the advisory firm had a limited catalog of expensive options.

So what can I do about it?

Well, here’s the good news. If you’re reading this you’re probably already a client of MY Wealth Planners® and you’re protected from these excessive and hidden costs. The bad news is, we don’t work for everyone, and as a result, many of your friends, family, and co-workers are probably being exposed to these expensive and questionable practices. So as always, you can make a difference by being an advocate, having conversations about these issues with those you care about, and when people need it, pointing them in the direction of a Fee-Only firm they can trust.