“The four most dangerous words in investing are ‘this time it’s different.’” Said Sir John Templeton, indicating the historical trend that investors often identify “unprecedented opportunities” to invest in, only to find that history repeats itself often when said opportunities crash or end up mediocre. After all, since the most valuable company on earth, Apple, had an initial public offering (IPO), another 1,396 companies have gone public just in the United States, and of course, that doesn’t begin to summarize the countless investment products, private offerings, crypto assets, venture capital, and other investment opportunities that have arisen. So even with the odds being .0716% that we could accurately have guessed which company was going to be the true “greatest investment possible” 41 years ago, we still see today that things like bitcoin and GameStop lure people into chasing returns for fear of missing out on this “opportunity like no other before it.” However, the research doesn’t support the idea that we’re good at chasing returns, or for that matter any better at protecting ourselves from losses. Today, we’re going to review some key lessons shared in recent research by Morningstar, which analyzed investor behavior and investment returns from last year’s COVID-Crash, by analyzing the actual investment behaviors of 520,000 individuals participating in over 660 ERISA retirement plans (such as 401(k)s.)

Who Self-Manages and Who Uses Professionals?

It’s important to understand the context. The current stereotype of a DIY investor is a young twenty-something with the Robinhood app on their phone, quickly trading options on margin so they can post screenshots of their 1,000% returns on the internet. However, this is actually quite far from the truth. While those people certainly exist, the current data shows that most young investors use professionally managed portfolios, whether through company retirement plan’s target-date funds or professionally managed portfolios by registered investment advisers who are hired to provide professional management for participants. In contrast, as Americans age, they become more and more likely to start selecting their own portfolios. There is an immediate and critical distinction here: professionally managed portfolios are universally going to have mitigated as much systemic risk as possible. Without getting too far into the technical weeds, you can only mitigate about 30% of what the market does to your investments. The other 70% of your returns are largely going to be driven by the asset classes you invest in and how concentrated those positions are. This is important because most DIY investors do not know how to effectively reduce market risk from their portfolios, and inadvertently, end up increasing or maximizing that market risk through overconcentration. As a result, their positives are magnified, creating the false impression that they’re “good at investing”, and the negatives are also magnified, which can result in crushing damage to investor’s life savings. Not only is an older DIY investor likely investing a larger sum of money, but they also have less time to recover from errors.

Change Isn’t Always a Good Thing

Self-directed investors often share several traits in common: they are older, have higher incomes, and have larger account balances to invest, and the Morningstar study found that all three of these traits were positively correlated with both overconfidence bias and with making changes to their portfolios during the downturn. Those who met all three criteria were significantly more likely to attempt to “derisk” their portfolios during the crash, which is fancy financial talk for “go to cash” or “reduce equity positions and increase fixed income positions”. But this is the exact opposite of what a good portfolio manager would do during a downturn. The concept of rebalancing in a market upcycle is a risk management tool: you sell off excess return from investments that have outperformed others in the portfolio and buy those underperformers in the expectation that the investments will likely outperform in the future, as the market goes through its various cycles. In a downturn, the same behavior occurs but with an inverse logic. You sell investments that are either outperforming or that are losing the least value to buy investments that are doing the worst in order to buy the cheapest possible investments during the downturn. This typically means that during a market crash like the COVID-crash, you would be selling your fixed-income assets (which were probably doing very well) to buy equities (which were likely down double-digits). But because self-directed investors were extremely likely to derisk, that meant they were selling equities well below their pre-crash value to buy fixed-income investments well above their pre-crash value, or even worse, were going to cash. And of course, the crash was so quick that those investors who went to cash often got out after taking a double-digit hit and didn’t get back into the market until well after it had recovered! To compound all of this, because self-directed investors often don’t fully understand how to manage their portfolio, these errors were further magnified. Those who de-risked their portfolio on average reduced their equity exposure by 20%, and have maintained that lack of equity exposure since the crash happened. This isn’t simply an issue of a failure to manage the portfolio well, but ultimately also a lack of basic investing knowledge: The majority of those who de-risked are still de-risked but have magnified the issues of their de-risked portfolio because they have not established some form of rebalancing. So not only are their portfolios well out of alignment with an efficient portfolio, they’re accepting greater than necessary market risk, and it’s only getting worse because they’re not using the basic tools of asset management to manage their investments.

So what are the damages?

Well, simply put, on average, the damage was 7.5% in the past year. That number, however, is extremely significant. Let’s think about a young self-directed investor. Let’s say it’s someone who had saved $10,000 up to the year before the crash happened. If this investor was 100% invested in a total stock market index fund before the crash and de-risked such as to underperform it by 7.5%, what is that going to cost them over a lifetime? Assuming they were 22 when this happened and they’re going to live to age 80 and that the total stock market index maintains its historic 10-year return for this person’s lifetime, it would have cost them a difference of $89,312 by age 60, and $1,183,027 by the time they passed away. This would be even more significantly aggravated if after the crash they hadn’t returned to their original aggressive stance, possibly magnifying that lagging portfolio throughout years or even decades of their career.

This Time I’m Different?

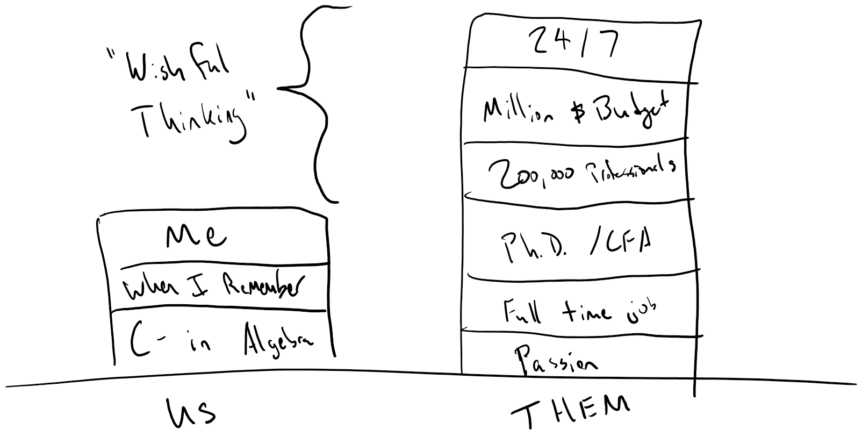

The average American has taken no classes in personal finance, corporate finance, any form of accounting, or even a math class at a level higher than trigonometry. The average American has not completed years of study in behavioral finance and does not make themselves a student of current events, economics, or market activity. Yet, the average self-directed investor is managing their money for one of a few reasons: Because they think it’s fun, because they think having their money managed is too expensive, or because they think they’re better than the professionals. At present, several hundred thousand people work in the portfolio management business in the United States. These professionals did take their finance courses, likely have degrees in the subject, years or decades of experience in the field, watch the markets constantly, and have enormous budgets of both time and money dedicated to watching market activity in an attempt to beat the market. On average, 75% of these professionals fail to do it every year, and statistically, almost none of them can do it for more than ten years in a row. Those that have done it for more than twenty can be counted on one hand. So let’s really stop and think about this for a moment. The evidence is overwhelming: Individuals are bad at investing. We hear news about Tesla, Gamestop, and Bitcoin millionaires occasionally, but fail to recognize that these investors had no factual or logical reason for putting all of their money in one place. They just happened to be incredibly lucky. We never read about the people who had all their money in Enron, Bear Sterns, or Lehman Brothers; they never get famous because they’re part of the statistically enormous group that lost everything, rather than the incredibly small minority that made it big on a wild bet. Investing can be entertaining, but when investing is entertaining, it’s because it’s riding the same emotional and hormonal mechanisms as gambling: Insert money, wait, and spike dopamine if we win. Fail to win? Insert more money and chase the dopamine high. As for expensive? Sure, spending money to have someone professionally manage your money costs more than not having your money managed. But the opportunity cost of making long-term errors in your investments is enormous, and grossly outweighs the out-of-pocket cost of management. Vanguard has studied and reported the findings over and over again: Professional management closes a gap larger than 3% every year between a self-directed investor and the returns they could get if they weren’t messing it up. That’s not to say that professional investors add 3% to the return (i.e., 10% Market + 3% Manager), but that they close the gap between the investor and the investments (i.e., 7% Self Directed + 3% Manager – 1% Fee). Again, this isn’t a pitch for hiring professional management. At MY Wealth Planners®, we’re very clear with clients: We’re not going to outperform the market or chase returns, we’re going to get the appropriate return that the market provides minus fees. Anyone who promises more than that can’t back up the claim for longer than a few years at most, but ultimately the evidence is overwhelming: self-directed investing is and remains a costly and dangerous process, and investors need to recognize that they are ill-equipped to self-manage, because as Sir John Templeton could have put it: “This time, I’m not different.”

Comments 2

Ahem, invest managers are not created equal and are not always better than the mattress safe. Early in my marriage, we had saved 100K and decided at that time we needed a manager. We went with a “reputable” firm, and they had us invest in limited partnerships. We lost 40K net and had years of a tax nightmare.

So, I would agree that investment advisors are better than individuals “in the main” but can also be unscrupulous.

Author

Absolutely true and a very well-told cautionary tale. The industry has changed a lot, but the critical thing for consumers to look for is a firm that has a fiduciary obligation to them and that doesn’t get paid by investment companies to sell their products but gets paid by you as a client to manage money for them!