I have a love-hate relationship with banks in general. While Banks have a long and questionable history, it is unquestionable that they’re a cornerstone institution in our society. That role isn’t only held by “bank banks”, but also by credit unions and assorted depositories of various types. Ultimately when I say bank going forward, you can assume we’re talking about all forms of “cash storing institutions.” The love-hate relationship comes along when a couple of basic functions of a banking institution break down along the way, and today we’re going to talk about the function of banks, what value they provide, and where they often fall short, and what you should do in consideration of these factors.

The Function of Banks

Banks were first established as a repository of physical currency. Predating computers or the internet, literal coins, bullion, or cash needed a somewhat secure home. Unless you were ultra-wealthy and could afford to build a personal Fort Knox, it made sense to outsource this responsibility to a financial institution. As time went on, entities such as the FDIC came into effect to provide levels of insurance for depositors and provide some level of assurance that a banking relationship wasn’t entirely relying on the efficacy of the bank’s management. Ultimately then, beyond the safer storage of capital, banks serve as a middleman. You see, your money at the bank doesn’t just sit quietly in a box waiting for the day you come to retrieve it. Rather, the bank lends out a significant percentage of the money it holds for its depositors as loans. These loans then provide the interest payments that in turn fund the operations of the bank and raise money for the paltry interest rates most banks pay their depositors (more on this in a moment.) In some instances, such as with mortgages, banks underwrite and fund the loan, then sell the loan onto a securitizing firm such as Fannie Mae and recoup their loan almost immediately but with a marginal fee for the production of the loan, thus allowing them to turn around and issue more loans shortly thereafter. Ultimately, a bank makes its money on the margin between the interest rate it will pay you and the rate at which it can get people to borrow money from it. In fact, while cash or deposits may appear as enormous assets on the balance sheet of the bank, they also represent significant liabilities on the balance sheet as well. However, so long as the bank maintains a minimum ratio of cash-to-liabilities, it can effectively do whatever it wants with its depositor’s funds, which explains how many banks can expand rapidly and seem to be the source of sponsorship for just about everything.

The Value of the Bank

It’s not to say that a bank is a miserly institution or otherwise greedily captures the margin between depositors and borrowers, but simply that there is a lack of a better alternative. Often a question arises in our lives about whether to lend money to friends or family. Many financial experts have pointed out that family-to-family or friend-to-friend lending not only often ends up becoming a point of conflict in a relationship, but further can become inefficient based on the timeliness (or lack thereof) of payments and other attempts to otherwise collect payment and interest. Outside of the potential pros and cons of lending personally comes the fact that those with extra money may not have a network in need of capital. Thus, while a cash-rich individual could put out a flyer offering to lend money to someone in need, this would both expose them to a significant risk of fraud but also represents a greater commitment of time and energy than might otherwise be worth it. Thus a bank has historically represented a low-yielding but safer and more efficient avenue to lending out money on a simple basis and netting some level of return for it. In the case of credit unions, the argument that being an owner improves the value of the relationship holds some weight, but unless you deposit millions at the institution, it’s likely that the quality of your day-to-day services is a much more relevant factor.

Where Banks Fall Short

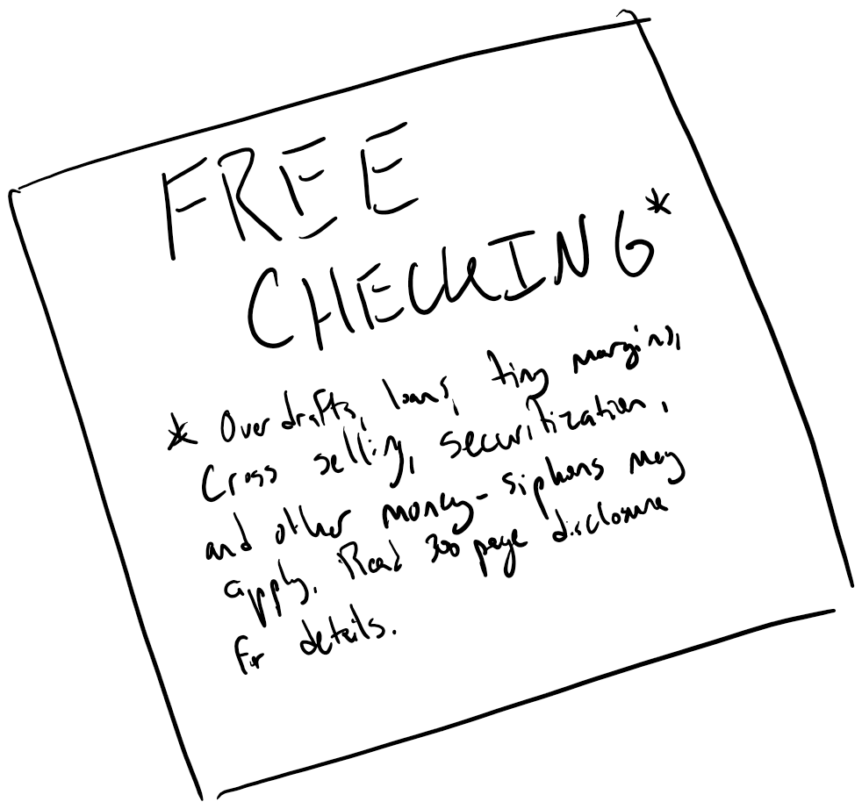

It’s no secret that interest rates are as low as they can go without being negative. This has been almost a persistent status for the financial sector since the recession in 2008 when the Federal Reserve cut rates to spur borrowing by the public which in turn would be spent in the economy to help increase employment and pick up the country after the crushing events of that year. Prior to the COVID pandemic, rates had climbed up slightly in an attempt to create some margin in the lending space, as low interest rates can be detrimental to retirement savings and otherwise gives little ammunition for the Federal Reserve to help in the event of future economic downturns. However, this persistent low rate environment has led to some consistent issues on the part of banking institutions and how they treat their customers. First is the issue of low rates themselves. At present, the national average yield on a savings account is .04% per year, or four cents per hundred dollars put into the institution. This is a result of the competition to provide low-interest rates for borrowers, and in turn, the narrow margins banks themselves must operate on. However, this is a somewhat artificial requirement. For example, there are now several banking institutions that are entirely virtual. Other than the operation of a home office for technology, management, and customer support, these institutions pass on the savings of forgoing a brick-and-mortar network of branches in the form of higher interest rates. One example, Ally Bank, has offered savings account rates between .5% and 2.2% over the past three years, moving the savings yield in tandem with the interest rate environment and effectively providing an equal margin to its customers as the market provided the opportunity. In other cases, one defense of the brick-and-mortar network has long been access to a network of ATMs and services; but for those customers whose only banking need is a debit card and a place to deposit their paycheck, the cost of those services is easily replaced by those banks that simply offer unlimited reimbursement of out-of-network ATM fees. Finally, we have the overdraft policy. While under fire for over a decade, overdraft fees amounted to over twelve billion dollars in pure profit for banking institutions. The defense of these fees has often been that it creates an administrative burden for the bank, but it’s the most laughable claim to say that a computer seeing that the available balance is less than the purchase attempted and declining the transaction is any more of a burden than processing a valid transaction, and certainly not to the tune of $35 per error.

What do you need from your bank?

That’s the fundamental question at heart. If the bank is nothing more than where your paychecks go and where you spend money from, seek out a virtual bank that has high yield savings and checking options for you. Don’t fret about money market or CD accounts, as they’re not yielding enough to matter at the moment. If you have a need for a lender, you may open an account with the bank you borrow from, but you shouldn’t base all of your financial resources on where your mortgage or auto loan gets paid. And if you have a genuine need for a banking relationship, such as being a business owner with a seasonal or cyclical business who will need ongoing financing, then that might be a good reason to engage with a local credit union or bank. But unless you have significant business or corporate complexity, there is little to no reason to do business with a large scale bank, which views its core offering of checking and savings not as a profit center or line of business worth serving, but as a lead generator for lending, insurance sales, or other lines of business.