When I started working on my Ph.D. back in 2020, the very first class was taught as a crash course in how to read research, understand the framework through which research was conducted, and to draft up a mock version of a study we’d like to perform. My excited first presentation during the culmination of the class was a study I wanted to perform, using data from financial planning software companies, to evaluate the efficacy of financial planning services between different service models. I argued that we could use net worth as a dependent variable and measure whether certain compensation models resulted in better or worse outcomes for clients. Then came the feedback.

It was almost immediately pointed out by the faculty that I had made two enormous errors in the assumptions of the experiment that I wanted to perform:

- That Net Worth as a dependent variable would only represent a select client set during a select period of time in their lives. Not all clients engaged in financial planning solely to enhance their current and future wealth, and because of the trend of wealth accumulation and decumulation (the “Life Cycle Hypothesis,”) the data would be inevitably skewed by significant factors outside of financial planning.

- That financial planning was such a broad service with so many different variations on how it was performed, that it would be fundamentally impossible to operationalize “what financial planning had been done” when looking at the data of thousands of financial plans across hundreds or thousands of firms and practitioners. Financial planning simply isn’t “one thing” that is done “one way” and attempts to compare are generally going to have issues.

All of that embarrassing history of learning to say that when we get into debates over financial planning fee models and services, we are generally arguing about something without having defined our terms. A fee-based advisor with a percentage of AUM model is arguing their service of a wrapped-in financial plan and annual meeting tempo against someone who is an advice only practitioner with a heavy emphasis on the life planning methodology and who breaks their planning engagement into a minimum of a year-long series of discovery meetings and iterative analyses, and so on. They’re both passionately speaking from experience about the efficacy of what they do for their clients; something that goes by the same name but is fundamentally different.

The Snuck Premise

Herein we then get to the other half of the argument: that of the fees for service. On a quicksand foundation of arguing about services that are similar but likely quite different, people get into an argument over the costs of financial planning. There is no doubting that some services cost dramatically more than others, and a natural response to that might be to argue that something being expensive undermines its value to the client. But this misses the point. Nine months ago, Dr. Michael Kothakota, the CFP Board’s first head of research, shared a link to the Freakonomics Podcast, which hosted an interview with a guest that argued “Managing your money is as easy as taking out the garbage.” In the span of a forty-six minute conversation, the host and his guest discussed investing, investment returns, the impact of costs on investment returns, and concluded that hiring an investment adviser was a waste of money because, paraphrasing, “if the return is X, then a return of X minus fees is going to be worse.” That comment is not in of itself wrong, but it hints at something that is almost always missing from the arguments over fees and compensation of advisors, and something that was entirely missing from the podcast: the value of what the fee is paying for.

Think about how enormous that omission is from the discussion. This is the same as talking about paying for any good or service without receiving the good or service. “Gas sure is expensive at four bucks a gallon, and it’s extra expensive when I pour it out on the ground instead of putting it in my car!” “My surgery cost hundreds of thousands of dollars! Did I mention that I didn’t go?” “My lawyer was so expensive that I fired her, so now I’m defending myself pro se!” Do you see the problem here? Through a combination of both failing to define what financial planning is and what the value of it is supposed to be, people arguing for or against certain types of fees are fundamentally arguing about a thing that not only hasn’t been defined, but often are doing so in the absence of what that thing is supposed to provide.

Financial Planning Theories

Fortunately there is some theory and research that attempts to pull all of this stuff together. Three examples stand out from the empirical literature: financial help seeking, economics of information, and financial planner client interaction theory.

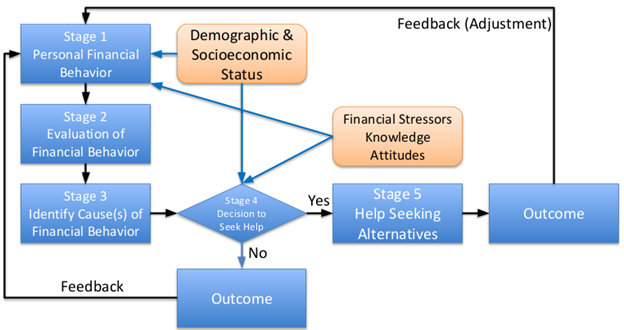

Financial help seeking is an empirical framework developed and refined in the nineties that attempts to address why someone would seek out financial help; specifically, financial advice or financial services, not simply asking to borrow money. While you could write an entire paper on the subject (I have,) the theory essentially boils down two major components: First, that people can be stressed by various events (job changes, family changes, financial changes, etc.) and that they use various coping mechanisms to address these changes, one of which can be engaging a financial professional, and that the likelihood of using a coping mechanism increases as the difference between expectations and reality grows (i.e. “I thought I’d have more saved for retirement by now” and “As I get older, concern of whether I can retire is growing faster than my savings!”) Second, that through an empirical model (seen below) a relationship between several independent variables is likely to affect whether someone seeks financial help, including financial stressors and negative financial behaviors which increase the likelihood of seeking help, and age and homeownership which decrease the likelihood of seeking help.

Financial Help-Seeking Theory Model

The Economics of Information is a broader economic theory regarding consumption of goods and services by consumers than one that solely applies to financial planning, but it’s valuable in understanding part of how consumers will ultimately engage in financial planning. At its simplest point, the theory points out that given unlimited time and resources, everyone would search for the best combination of price and quality possible. However, time and resources are finite, so consumers will often search only so long as the return on the search is valuable. For example, someone is likely to spend more time researching something that has a significant cost than something with a nominal cost; however, the cost of search is heavily affected by the opportunity costs of the search. Searching for the best price or service is a low-cost activity to someone with no or low income because there is little to no tradeoff for the time they spend searching, while the cost of search is very high for a professional. Ultimately, people may elect to engage financial planners (either on a validation or delegation basis) as a cost-benefit tradeoff for the opportunity cost of “doing it themselves” (and I mean that more broadly than implementation, even something as innocuous as “am I doing this plan right” vs. outsourcing investment management) versus having a professional do it for them. This is further reinforced by subsequent research that shows that often consumers will pay a premium to avoid errors (or as the author called it, avoiding lemons.)

Financial Planner Client Interaction Theory, a more recent addition to the empirical literature, simplifies all of this into a consideration that even an individual financial planner can evaluate despite the potential lack of similarity between financial planner’s services and the clients they serve: consumers will engage in the financial planning process (whatever that may be) so long as they perceive a marginal benefit in doing so. Summed up, if the value of paying $1 to the financial planner returns >$1 to the client, they are going to continue engaging that financial planner. What’s critical here is both valuing the return on the dollar: it doesn’t have to be literal, it could be peace of mind, an opportunity cost tradeoff, avoidance of errors or reduction of risk, or any other number of things other than a literal return on investment. So long as the client perceives the value, the relationship is likely to continue. It is often argued in the fee debate that consumers do not fully understand the cost they’re paying and that unbeknownst to them, the cost is actually greater than the return. That point is not without merit, but ultimately does have to be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, and sweeping generalizations are going to fail because its exceptions will invalidate the generalizations as a rule.

There Are Legal Issues As Well

Beyond the effort and issues of debating terms and costs in the vacuum of Twitter, comes the fact that there are more complicated forces at work here than simply the cost of planning, the reasons a consumer might engage in planning, and the value of planning itself. Financial planning is regulated by a hybrid framework of the SEC, state administrators, and state insurance commissioners. None of these entities have explicit statutory mandates to regulate financial planning, but have ultimately come together over the past few decades to regard financial planning through their respective lenses and address financial planning through the statutory guidance of their core responsibilities. The SEC and state securities administrators view financial planning as an additive service of investment advice; this means that even when a financial planner is advice only and does not have any assets under management, the regulators view the planning activity as investment advice and regulate it as such. At the same time, state insurance commissioners view financial planning as a sales tool and incidental advice pursuant to the sale of an insurance product. Thus, while someone might go to a financial planner for something like financial therapy for a spending issue or portfolio management stress reduction, the transaction between the planner (whether hourly, fixed fee, or otherwise) is going to be treated as either an incredibly roundabout investment advice offering or a remarkably strange insurance product pitch.

Even outside of the direct service of financial planning, there are several statutory obligations that are enshrined in the majority of state laws. The Uniform Prudent Investor Act (the law of 46 states) and the Uniform Prudent Management of Institutional Funds Act (the law of all states) lay out explicit prescriptions for anyone who engages in the business of investment advice (hint: a subset of financial planning), which provide the common “prudent man rule,” along with other explicit fiduciary considerations:

- That the totality of a client’s circumstances be considered in the allocation of assets to accomplish the goals of the client;

- That diversification is explicitly required as a duty;

- That no type of investment is inherently imprudent, but that outright speculation is not protected behavior for fiduciaries;

- That delegation of investment management to qualified third parties is permitted.

All of this to sum up the point that the fiduciary obligations of a financial planner to their clients are multi-variant and complex both from an applied standpoint and from a view of the repercussions for failure to adhere to the legal mandates of the laws that govern financial planning. Boiling arguments around “what financial planning is” down to simple quips and quotes for internet points entirely misses the nuance that not all financial planners are going to be regulated equally and that not all financial planning is the same. Debating fees is almost entirely pointless when the value fails to be taken into account, particularly when those fees may be arbitrarily influenced by the regulatory framework of the state a practitioner works in. For example, some planners might argue an hourly rate is the best way to serve all clients, but in certain states, hourly fees are capped at $150 (Utah) or less than $250 (Missouri), or in other states it might be permissible to charge unlimited asset-based fees but outright banned to charge a subscription (Washington), or in another you may be able to use any model you like, but up-front fees cannot exceed $1,800 (Pennsylvania). All of these examples to point out that the business of how someone offers financial planning is not solely up to the financial planner and is also subject to outside forces.

The Simple Fact is: You Don’t Know

All of this context, argument, and empirical literature is here to make a point: Whether you’re an hourly advice-only planner, a fee-based AUM planner, a subscription-based fee-only planner, or any other variation of planner, you simply don’t know whether you’re right about financial planning services and whether a fee is reasonable or not. Don’t start protesting, be honest with yourself. What you have is an opinion. Maybe a reasonable opinion, maybe one that’s founded on decades of experience and perspective, maybe one that you formed in the last year or two. That opinion might be informed by the harm you’ve seen unreasonable fees for inadequate services do to consumers, or the discovery of bad financial implements in financial plans that were likely the result of conflicts of interest related to the licenses, limitations, or compensation of the person who recommended them. You may have several, dozens, or even hundreds of personal experiences with clients who have come to you now because the last professional didn’t serve them the way they needed. None of that is invalid, but ultimately if you find yourself shouting at people on the internet, telling them that their way is wrong but you have found the light and the truth and the way for financial planners to serve and charge their clients, check yourself. Because fee debates are pointless when you haven’t defined your terms (“What is the type of financial planning and service we’re talking about here?”), when you haven’t discussed the specifics of the hypothetical client you’re supposedly advocating for, and when the value of planning for that hypothetical client is entirely omitted from the discussion.

There Is Some Light on the Horizon

Despite all the issues and complexities I’ve raised so far, there is some light on the horizon for these issues. As CFP® Certification adoption grows, the likelihood of a statutory framework explicitly to address the offering of financial planning increases. The CFP Board itself is developing a longitudinal study to examine the value and effects of financial planning over time, a thing that does not exist in the current secondary data available today. The trend of financial advice as a sales tool is slowly dwindling in favor of financial advice as a service, which helps separate some of the more obvious conflicts of interest between those giving the advice and those seeking it. Even on the theoretical side, work is being done at Kansas State University to develop a “Theory of Financial Planning” that will attempt to measure both the financial planning that can be done by someone on their own and the measurable value of the planning that can be done by a financial planner. None of these things alone will bring all the answers and information we need to know what is best for every single person out there, but it does provide a glimmer of hope that some day we’ll actually have something to base these discussions on. Until then, it’s complicated, and no one is being helped by screaming opinions at each other on the internet.

Comments 1

Pingback: The Allianz Scandal and Altruist Announcement